The 1940s were a time of big changes for St. Louis, Missouri. The city was still recovering from the Great Depression when World War II began. This war affected almost everything in St. Louis. Factories got busy making supplies for the war. Many people worked long hours, and others made sacrifices at home to help. The war changed the city’s jobs, its neighborhoods, and the daily lives of its people.

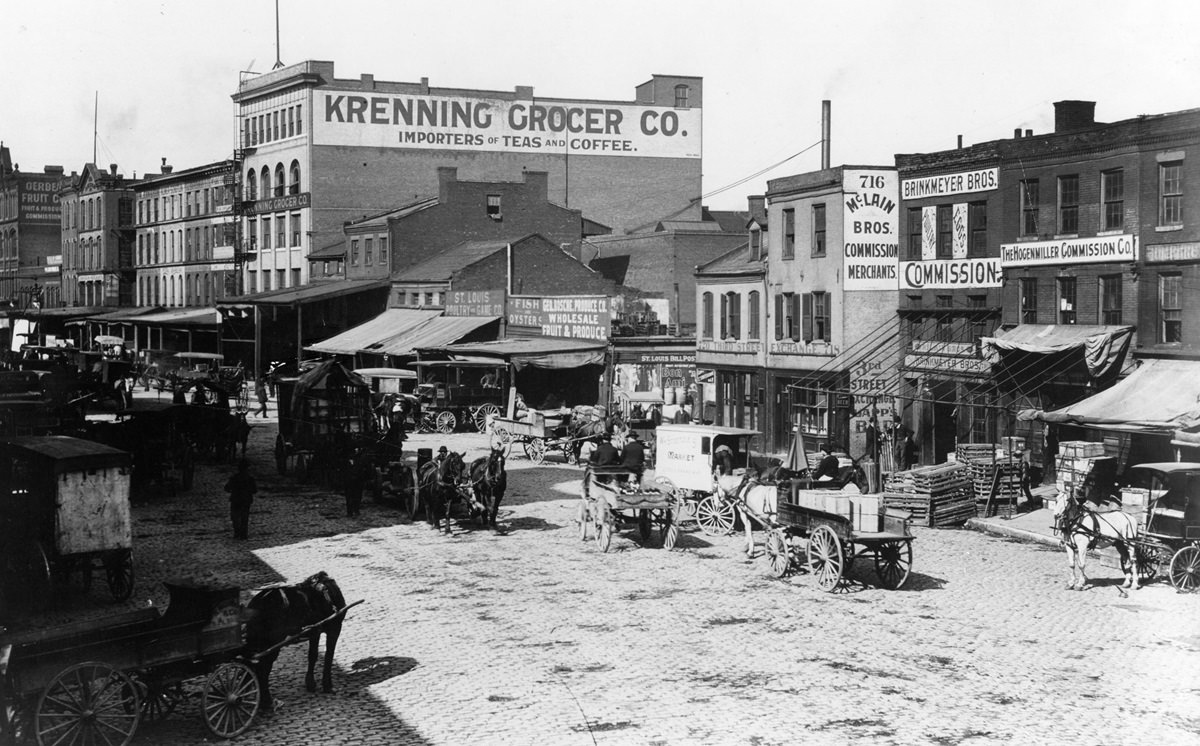

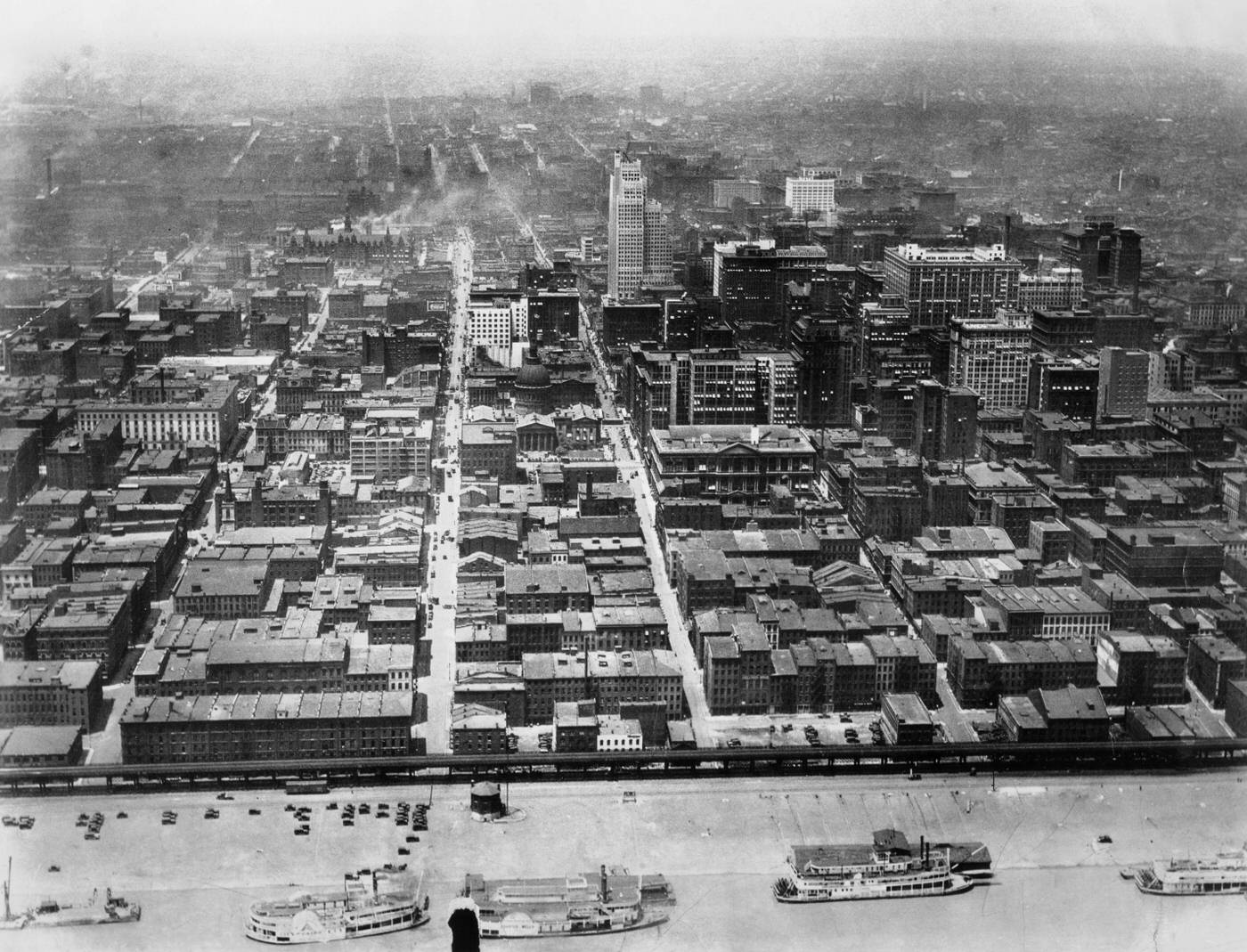

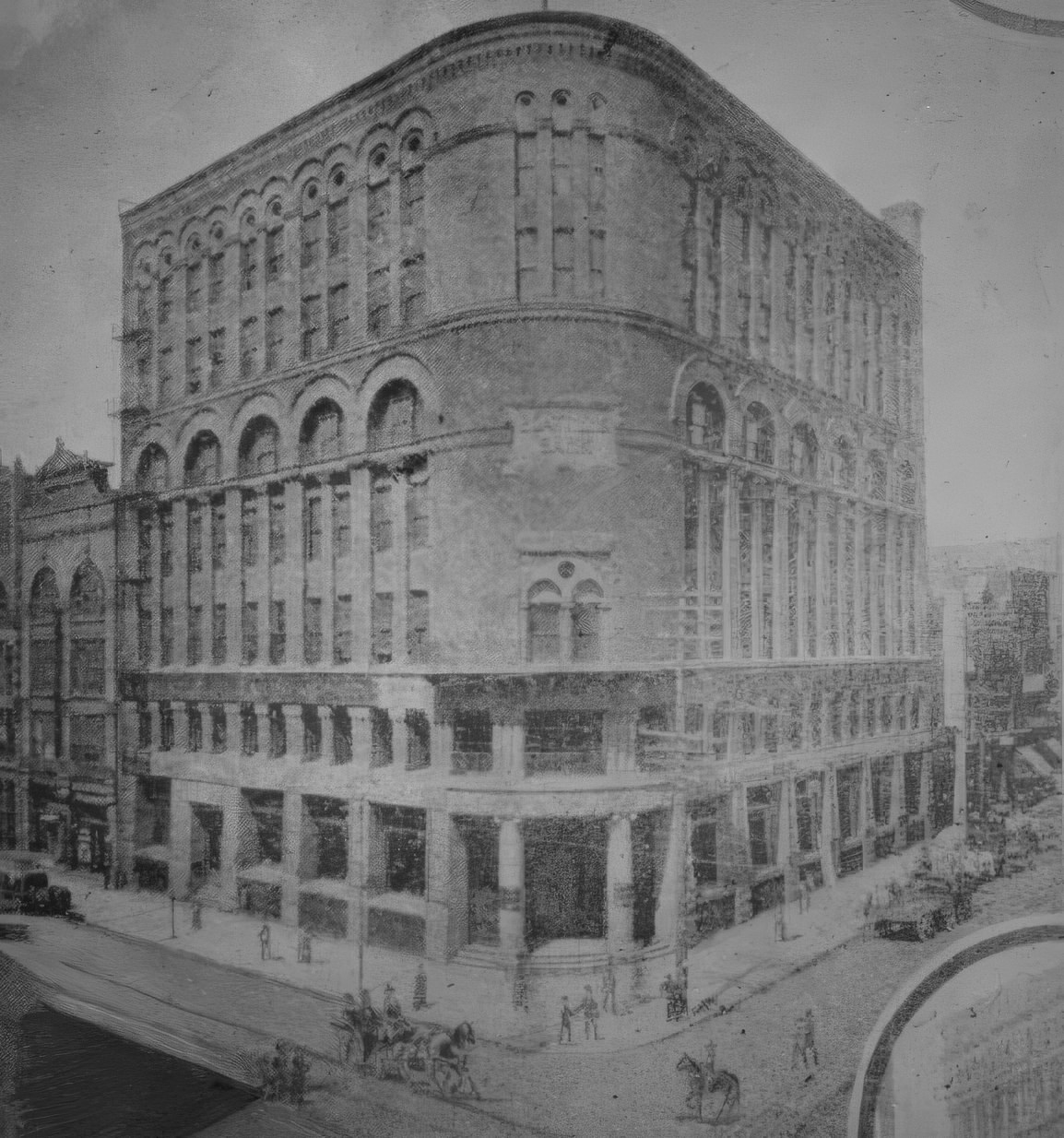

St. Louis entered the decade with a diverse industrial base. Food processing, chemical production, and steelmaking were significant sectors, alongside a robust shoe and garment industry concentrated along Washington Avenue. The International Shoe Company stood out as one of the city’s largest employers, a major player in the national market. This existing industrial capacity, though strained by the Depression, held the potential for future growth and adaptation.

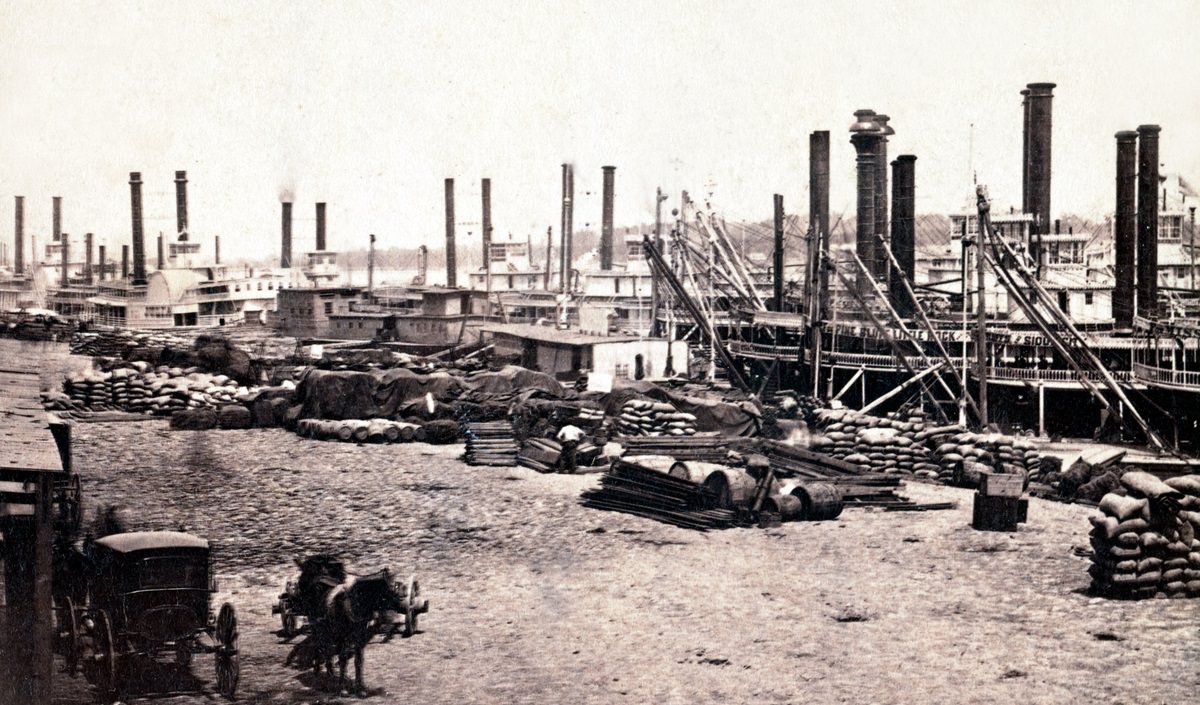

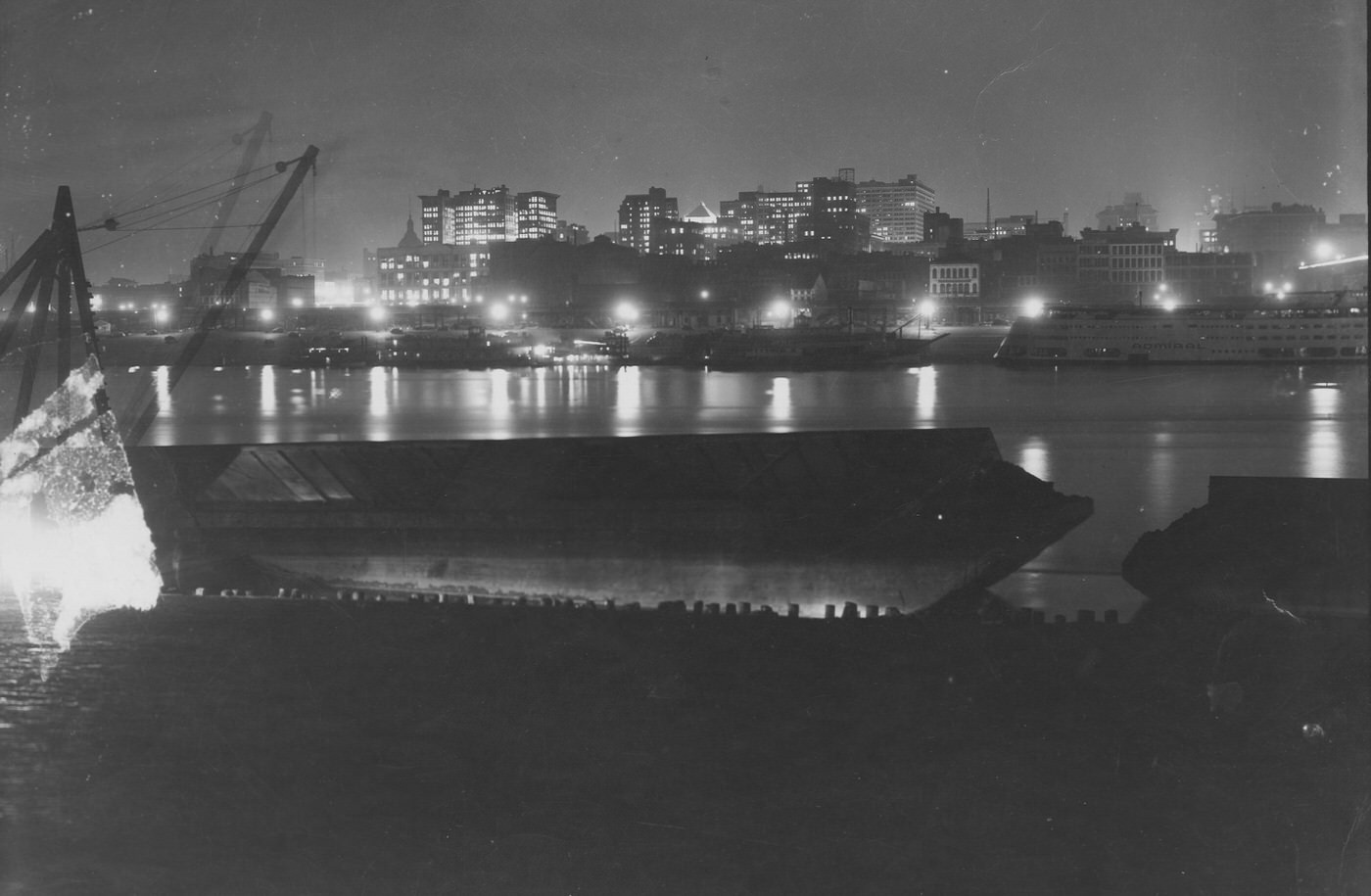

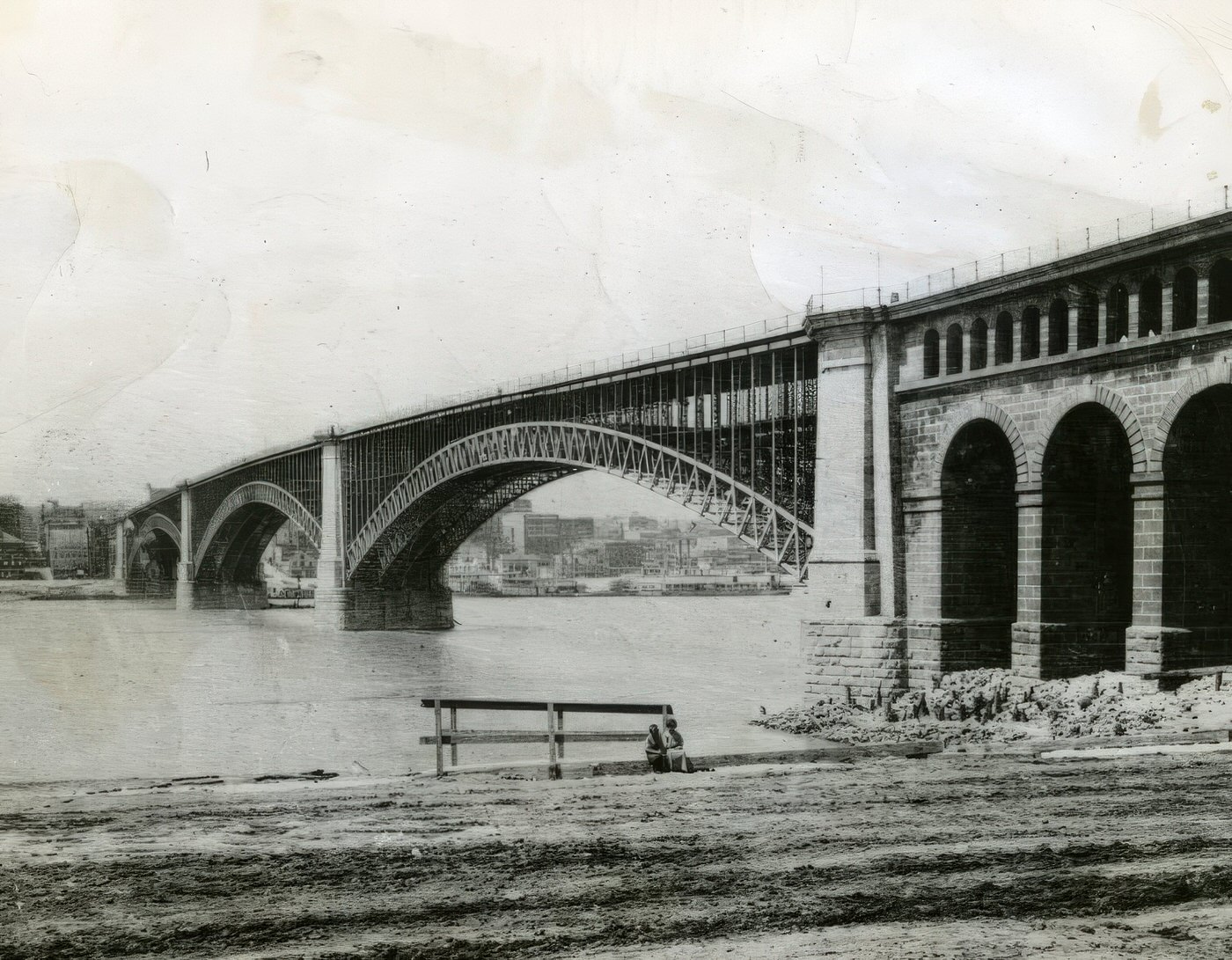

The city’s lifeblood, the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, continued to be vital arteries for commerce. By 1940, a series of infrastructure projects, including the completion of twenty-nine locks and dams, had enhanced navigation. These improvements allowed heavier commercial barges to move upstream, carrying essential goods like oil, coal, chemicals, fertilizers, and agricultural products, reinforcing St. Louis’s role as a key transportation hub.

However, the city also faced significant environmental challenges. The widespread burning of soft coal for heating and industry cast a pall of smoke over St. Louis, a persistent air pollution problem that civic leaders were beginning to confront.

The economic difficulties of the 1930s created a substantial pool of available labor. At the same time, the infrastructure improvements from New Deal projects and the city’s established, varied industries created a foundation that, while not intentionally designed for war, positioned St. Louis to respond effectively when the demands of wartime production arrived. The enhanced river navigation capabilities further solidified its logistical strength, readying the city for the immense tasks that lay ahead.

The War Machine: St. Louis Industries Answer the Call

The 1940s were overwhelmingly defined by World War II. Following the United States’ entry into the war in December 1941, St. Louis underwent a rapid and dramatic transformation, becoming a crucial center for war production.

Aviation Ascendant

The city’s role in the skies was significant. Three major aircraft companies – Curtiss-Wright, Robertson, and the McDonnell Aircraft Company – operated in St. Louis. Together, they produced more than 3,000 airplanes for the military effort. Lambert Field became the central manufacturing base for these aviation giants. Beyond production, Lambert Field also served as an active Naval Air Station, where many pilots received their training. This cemented St. Louis’s position as a key contributor to America’s “Arsenal of Democracy,” particularly in the vital aircraft manufacturing sector, an industry that would remain important to the city’s economy long after the war ended.

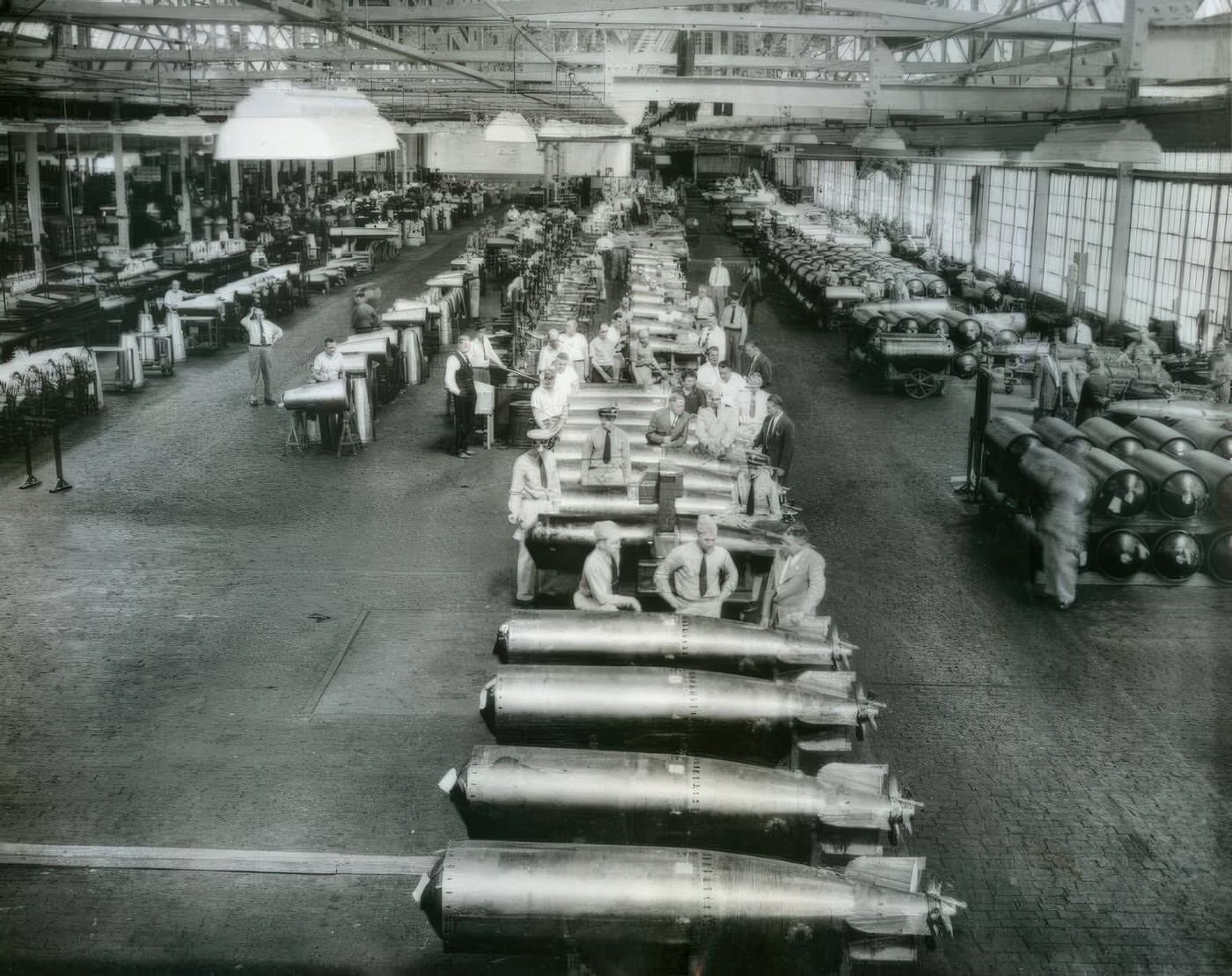

Munitions Metropolis

St. Louis was home to the world’s largest production facility for.30-caliber and.50-caliber ammunition: the St. Louis Ordnance Plant on Goodfellow Boulevard. Remarkably, production at this massive plant began on December 16, 1941, a mere nine days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The facility operated around the clock, seven days a week. At its peak in the summer of 1943, the St. Louis Ordnance Plant employed 35,000 people and churned out an astonishing 250 million cartridges each month. Notably, half of this immense workforce consisted of women, stepping into industrial roles in unprecedented numbers. African American workers also sought employment at the plant, initially facing resistance and segregated conditions. Government intervention eventually led to more inclusive hiring practices, though challenges remained. The sheer scale and speed of operations at the Ordnance Plant highlight the urgency of the war effort, while its diverse workforce reflected broader societal shifts accelerated by wartime labor demands.

Rolling Stock for Victory

The St. Louis Car Company, historically known for manufacturing streetcars and other rail equipment, pivoted its production to support the war. Its primary contributions to the war effort included tracked amphibious landing craft (LVTs), electric generator sets, and ammunition cars. Landing craft became the company’s dominant wartime product, accounting for nearly 80% of its contracts, which totaled over $54 million. The company is estimated to have built 2,431 LVTs of various models. This shift demonstrated the adaptability of St. Louis’s existing industries, with the company’s prior experience in electrically powered equipment making the production of generator sets a logical extension of its capabilities.

Training Grounds

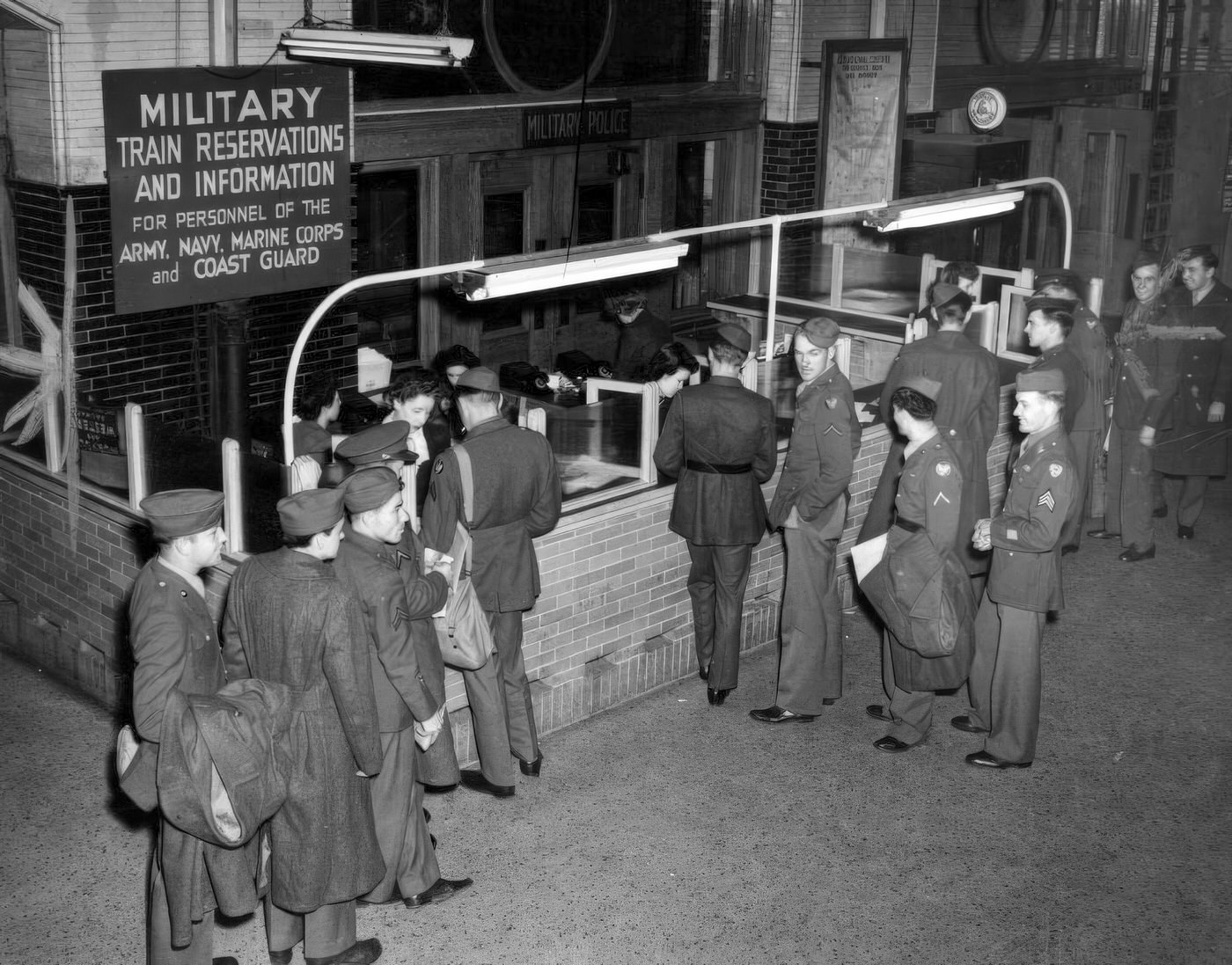

Beyond manufacturing, St. Louis also played a critical role in training military personnel. Scott Field, later known as Scott Air Force Base, was instrumental in training pilots in advanced skills such as instrument and night flying, navigation, and photography. Its primary mission, however, was to train skilled radio operators and maintainers, graduating over 77,000 by the war’s end. Jefferson Barracks served as a major reception center for troops drafted into the military. It was also an important basic training site for the Army and later became the first Army Air Corps Training Site. At its peak, Jefferson Barracks covered 1,518 acres and could accommodate 16 officers and 1,500 enlisted personnel. These facilities were indispensable for processing and preparing the vast numbers of soldiers, sailors, and airmen required for the global conflict.

The immense industrial activity driven by war contracts served as a powerful economic engine, effectively pulling St. Louis out of the lingering effects of the Great Depression and creating jobs on an unprecedented scale. This boom, however, also acted as a social crucible. It drew diverse groups, including many women and African Americans participating in the Great Migration, into industrial workplaces, often for the first time. This influx highlighted and sometimes exacerbated existing racial and gender inequalities, making places like the St. Louis Ordnance Plant sites of not only massive production but also early struggles for civil rights and fair employment. The war machine, therefore, was not just manufacturing armaments; it was actively reshaping the city’s social and economic landscape.

The Home Front: Daily Life and Civilian Sacrifice

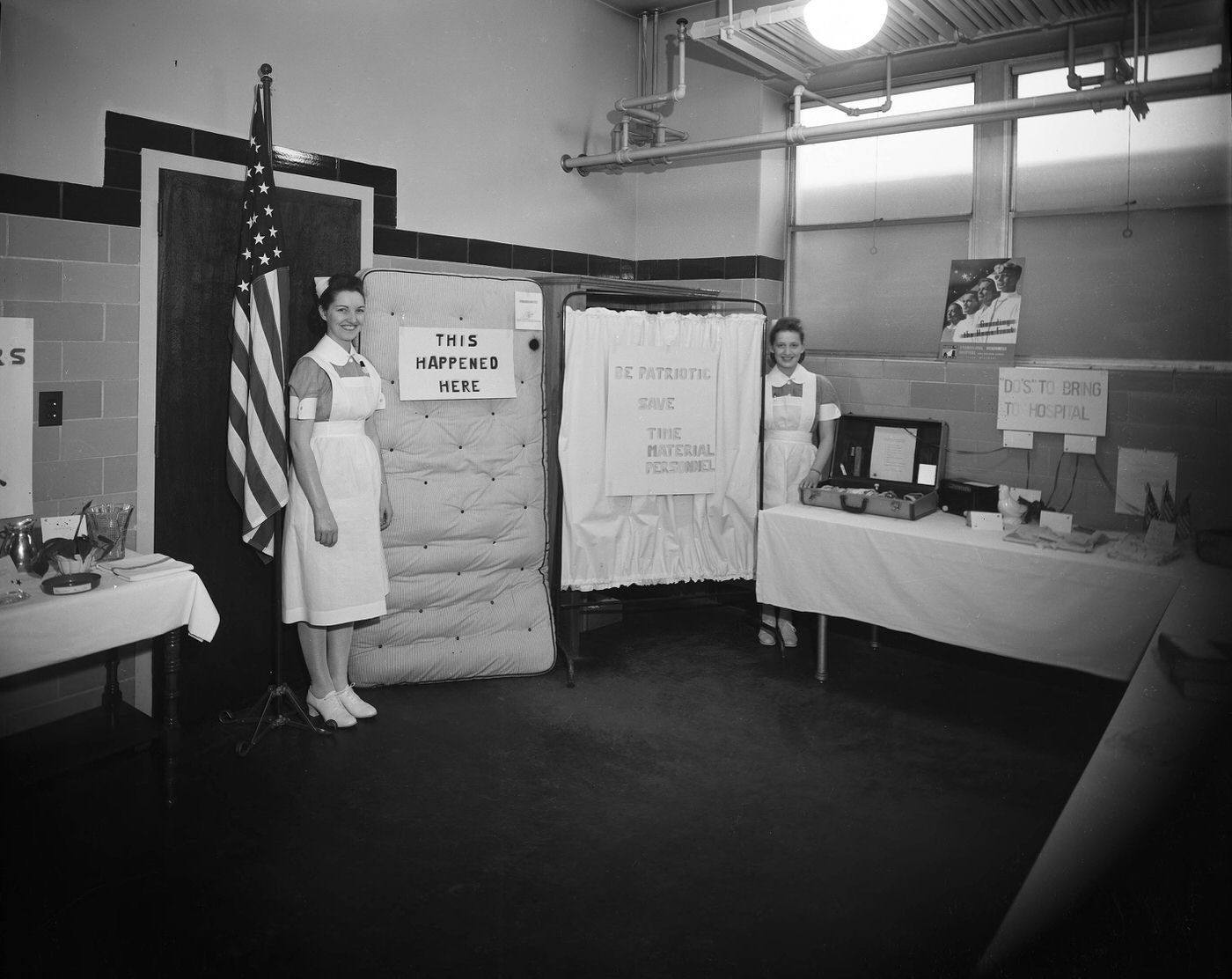

While St. Louis industries hummed with war production, the city’s civilian population was deeply engaged in the war effort on the home front. Daily life was marked by sacrifices, community initiatives, and a collective determination to support the troops overseas.

To ensure that the military had adequate supplies and to prevent inflation, the federal government, through the Office of Price Administration (OPA), instituted a comprehensive rationing program in May 1942. St. Louisans, like Americans across the country, adapted to limits on a wide array of goods. Sugar was the first food item to be rationed, beginning in April 1942, followed by gasoline, tires, meat, butter, canned goods, coffee, shoes, and fuel oil. Families received ration books containing stamps that were required to purchase their allotted share of these essential items. In the suburban community of St. Louis Park, for example, 13,500 ration books were distributed by 1945, illustrating the widespread nature of the program.

Public understanding of rationing varied. One St. Louis resident, quoted in August 1942, believed sugar rationing was more for public health than due to actual shortages, a sentiment that reflected some of the skepticism or misinformation that circulated. Newspapers like the St. Louis Post-Dispatch played a role in informing the public, publishing articles about civilian quotas for items such as canned vegetables and soups. Rationing profoundly affected daily routines, demanding careful household planning and resourcefulness from St. Louis families.

Civilians actively contributed to financing the war through the purchase of War Bonds. Aggressive promotional campaigns encouraged investment, and Missourians, including those in St. Louis, responded generously, purchasing over $3 billion in bonds throughout the war. Scrap drives became a common sight, as communities collected vital materials like metal (iron, tin cans), rubber, and paper, which were recycled into war materials. In St. Louis Park, housewives collected an impressive nine tons of tin in a single drive in March 1943.

“Victory Gardens” sprouted in backyards and community plots across the city. Residents grew their own vegetables to supplement rationed food supplies and reduce the strain on the national food distribution system. The St. Louis Red Cross was a hub of volunteer activity, with members teaching surgical dressing classes and local businesses donating to support their efforts. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch also promoted initiatives like the “Victory Book Campaign,” which collected books for servicemen. These collective efforts fostered a powerful sense of unity and direct participation in the war, transforming the home front into an active zone of production and conservation.

Eyes on the Skies: Civil Defense

Though far from the battle lines, St. Louis prepared for the possibility of enemy attack. Civilian Defense Councils were established; the council in St. Louis Park, for instance, boasted 1,000 members. Neighboring St. Charles County also organized robust civil defense measures, including an Aircraft Warning Corps that scanned the skies. Air raid wardens were appointed throughout neighborhoods. Their duties included educating residents on blackout procedures, explaining what to do during an air raid, and teaching methods for fighting incendiary bombs. Regular blackout drills and air raid drills were conducted to ensure preparedness. As part of these preparations, St. Louis city inspectors designated 200 sites to serve as public air raid shelters. While St. Louis was never directly bombed, these civil defense measures were crucial for maintaining public morale, preparing the civilian population for potential threats, and reinforcing the serious nature of the global conflict.

The myriad home front activities – from rationing and bond drives to civil defense drills – forged a strong sense of collective purpose and patriotism among St. Louisans. These shared experiences brought together different segments of society in a common cause. However, this unity existed alongside deep-seated social divisions. For instance, while all citizens were called upon to make sacrifices for the war effort, African Americans were simultaneously fighting for equal employment opportunities in the very defense plants they were encouraged to support through bond purchases and scrap drives. This highlights the complex reality that the “unity” of the home front did not erase, and in some cases even underscored, pre-existing societal fissures related to race and equality.

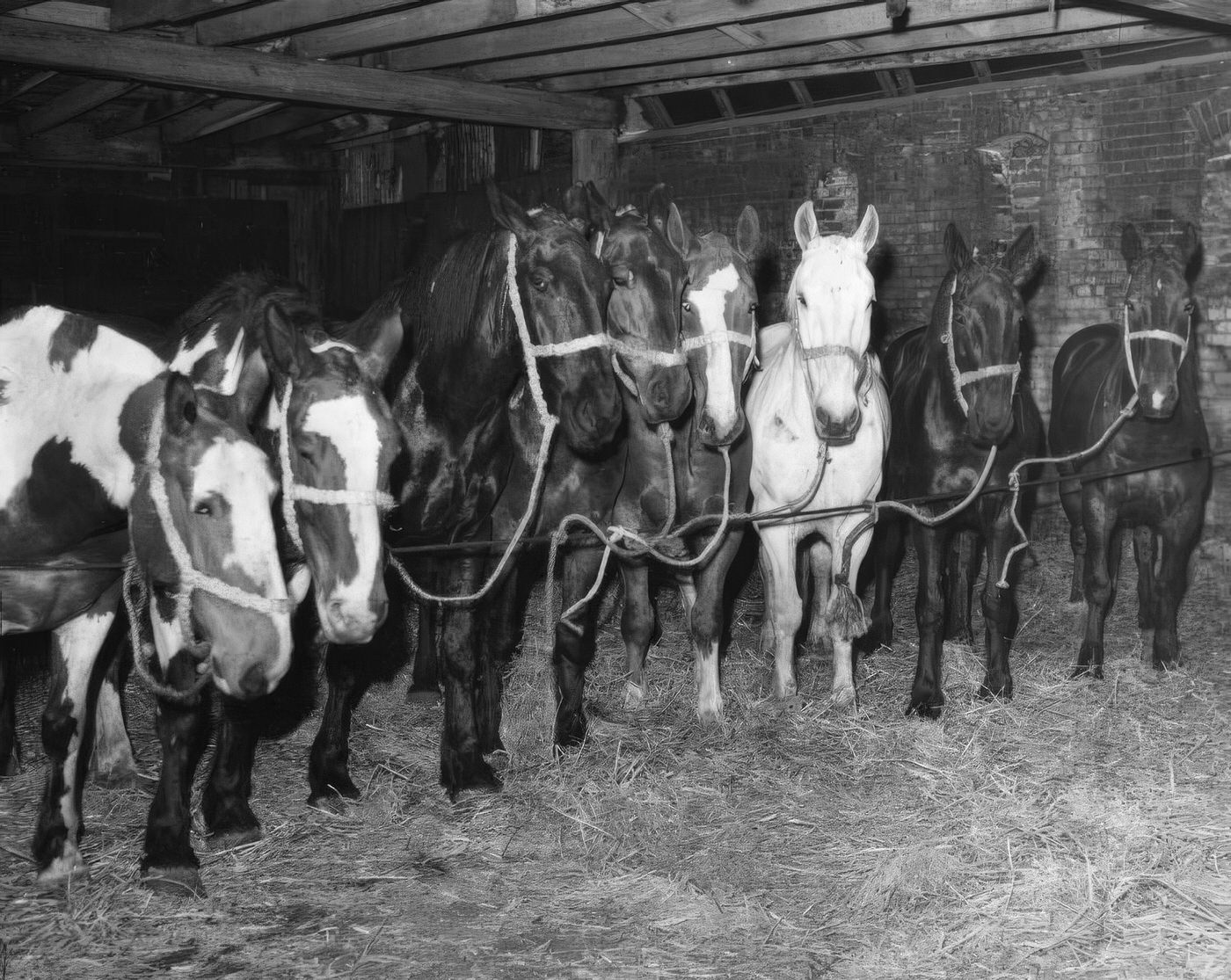

A City in Motion: Population and Housing

The 1940s brought significant demographic shifts and housing challenges to St. Louis, driven by wartime opportunities and post-war adjustments. The Second Great Migration, a period of intense movement of African Americans from the rural South to urban centers in the North and Midwest, continued throughout the 1940s. Drawn by the promise of economic opportunities in burgeoning war industries and seeking to escape the oppressive Jim Crow laws of the South, many African Americans chose St. Louis as their new home. This migration significantly altered the city’s demographic landscape. The Black population of St. Louis city increased from 13.3% in 1940 to 18%, or 154,000 people, by 1950. The total population of St. Louis City in 1940 was approximately 816,000. By 1950, the city reached its peak population of around 856,000 to 857,000 residents.

This influx of new residents, combined with years of neglect during the Great Depression and the diversion of resources during World War II, led to severe housing problems. St. Louis faced conditions of overcrowding, and much of its existing housing stock was old and deteriorating. A 1947 official survey revealed that 33,000 homes in the city still relied on communal toilets. Many St. Louisans lived in “cold water flats,” which lacked modern amenities, and relied on coal for heating, a practice that also contributed to the city’s air pollution. Air conditioning was a rarity. Overcrowding was a common hardship, with anecdotal accounts of families having as many as nine children sleeping in a single bedroom. The end of World War II exacerbated these housing shortages as veterans returned home seeking places to live. In response to these pressing needs, public housing initiatives were undertaken. Projects like Carr Square, designated for African American residents, and Clinton-Peabody Terrace, for white residents, were constructed between 1939 and 1942, providing over 1,300 new housing units.

The passage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, had a profound impact on housing patterns. The bill provided veterans with government-backed loans, making homeownership more accessible. This facilitated a significant movement of families, particularly white veterans, towards newly developing suburban areas in St. Louis County.

As a response to the acute post-war housing shortage, innovative housing solutions emerged. One such solution was the Lustron home, a factory-built house made of porcelain enamel steel panels. These prefabricated homes were marketed as durable, termite-proof, rodent-proof, and easy to clean. The first Lustron house for public sale in the St. Louis area arrived in the suburb of Webster Groves in January 1949. Modern Housing Corporation served as a local dealer for these homes. Approximately 24 Lustron homes were erected in the St. Louis region, with a notable concentration in Brentwood on Litzinger Road. These homes, typically priced around $7,000, represented an attempt to quickly address the housing demand with modern materials and construction techniques.

The demographic and housing trends of the 1940s laid the groundwork for significant urban challenges in the decades to follow. The combination of a growing population due to the Great Migration and pre-existing, deteriorating housing stock created immense pressure within the city limits. While the GI Bill offered new opportunities for homeownership, discriminatory practices such as redlining often limited housing choices for African American families, concentrating them in older city neighborhoods while white families increasingly moved to the suburbs. This dynamic contributed to the beginnings of the “white flight” phenomenon and the spatial segregation that would define much of St. Louis’s post-war development. Early public housing projects, though intended to alleviate shortages, were also often built along segregated lines, further shaping the city’s social geography.

Struggles for Equality and Fair Work

The 1940s in St. Louis were not only shaped by global conflict but also by significant local struggles for racial equality and fair employment practices. The war effort itself became a focal point for these challenges.

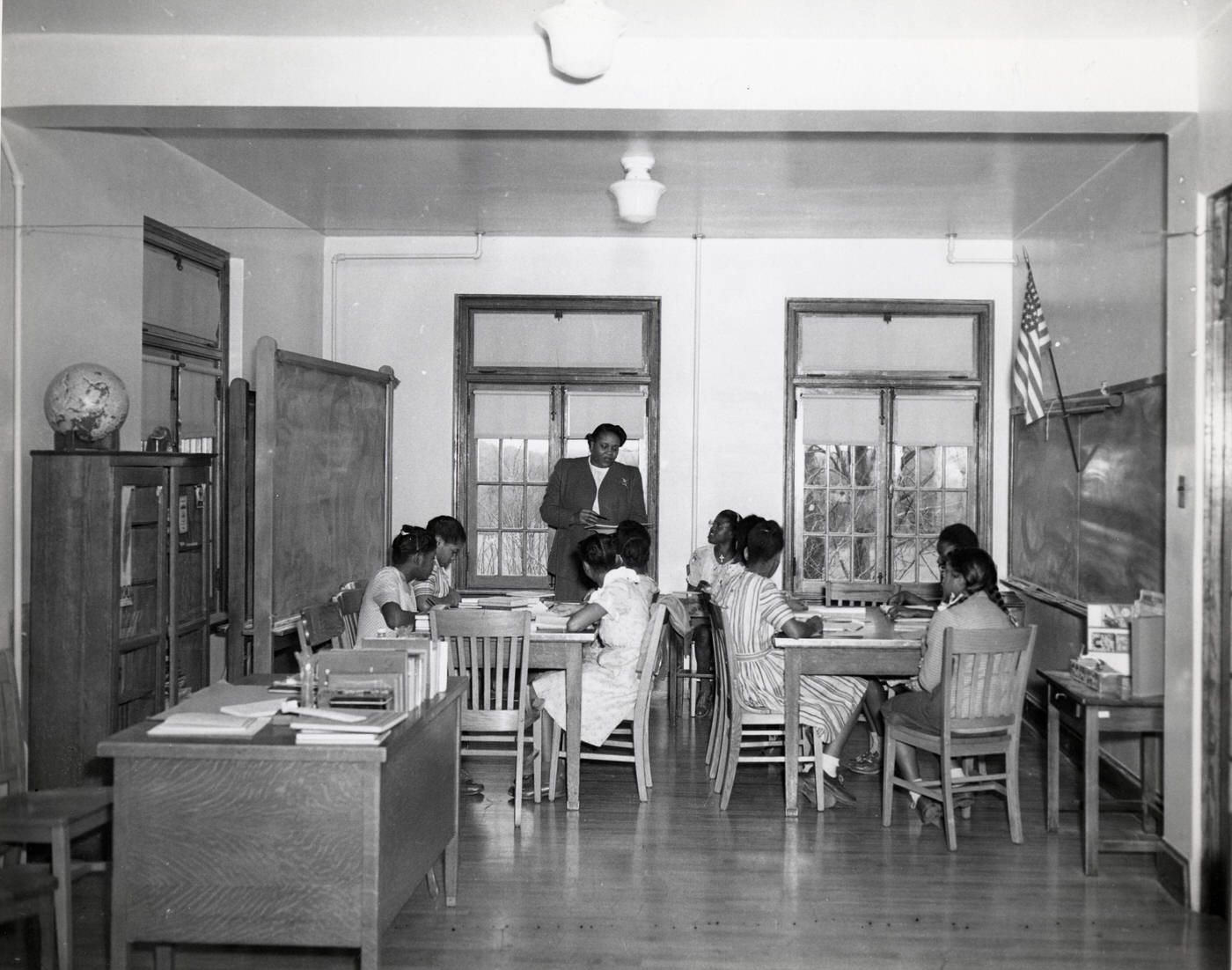

The demands of World War II created unprecedented job opportunities in St. Louis’s defense plants, drawing large numbers of African Americans and women into the industrial workforce. At the massive St. Louis Ordnance Plant, for example, women made up half of the employees. However, the path to these jobs was often fraught with discrimination, particularly for African American workers. The St. Louis Ordnance Plant initially refused to hire Black workers, which led to organized protests.

In response to nationwide pressure and the threat of a large-scale march on Washington, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in June 1941. This order established the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) and aimed to forbid racial discrimination in government hiring and defense industry training programs. While the FEPC’s enforcement power was limited, its existence, coupled with continued activism, did lead to some changes. At the St. Louis Ordnance Plant, this initially resulted in the creation of segregated production lines for Black workers. It was not until a 1944 government order that the plant was mandated to fully integrate its workforce. The wartime labor shortage, therefore, forced a partial opening of previously closed doors for marginalized groups, but deeply entrenched discriminatory practices persisted, setting the stage for ongoing civil rights battles.

Early Civil Rights Activism

St. Louis was a significant site of early civil rights activism during the 1940s. The St. Louis chapter of the March on Washington Movement (MOWM), effectively organized by local leaders David M. Grant and Theodore D. McNeal, was particularly active. In May and June of 1942, MOWM led protests against the United States Cartridge Company concerning the layoff of African American employees. These demonstrations resulted in increased hiring and training opportunities for Black workers at the plant.

In 1943, the MOWM turned its attention to the Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, organizing parades with over 300 participants to protest discriminatory hiring practices. These actions successfully pressured the company to open offices staffed by Black employees in Black neighborhoods.

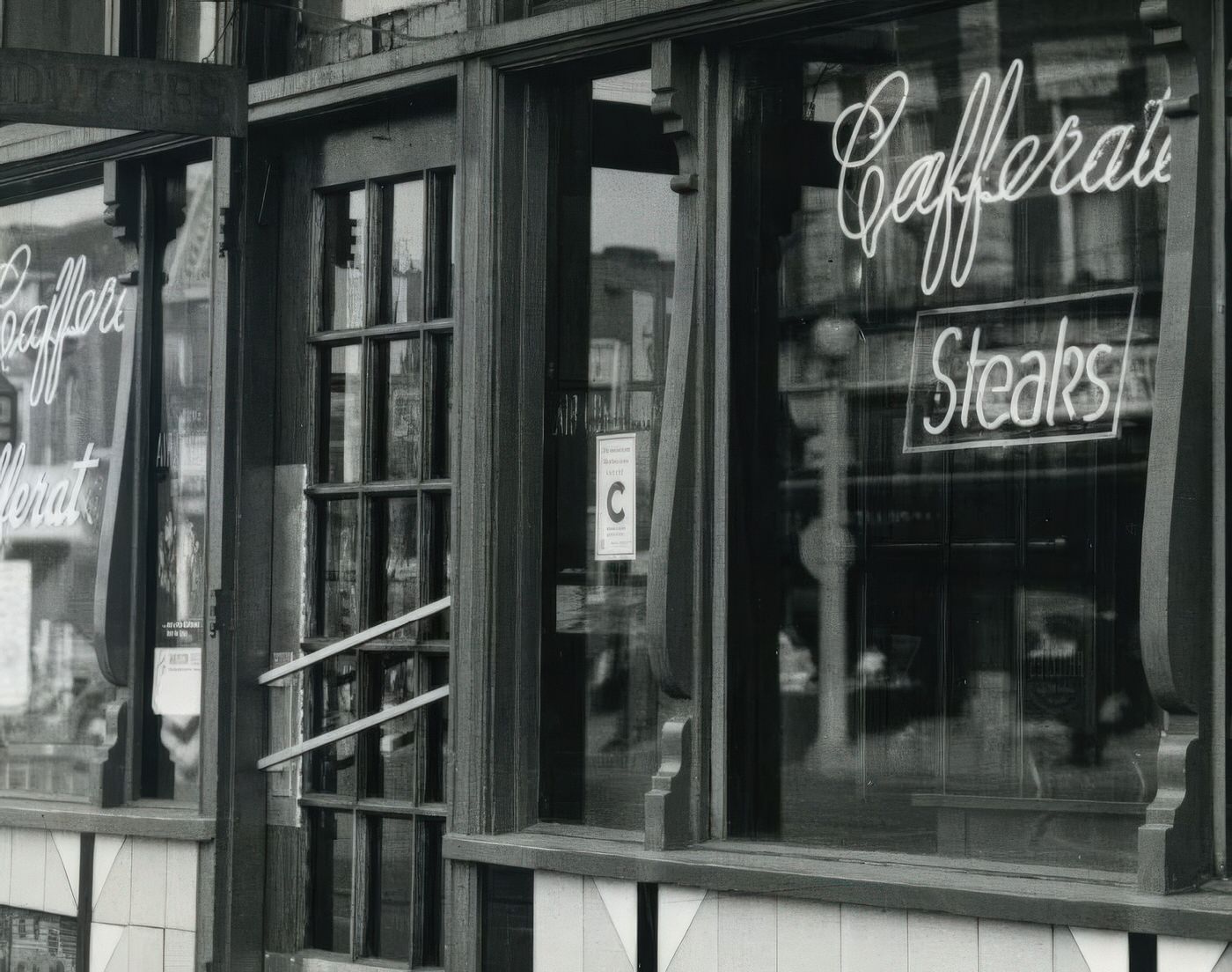

Another pioneering effort was undertaken by the all-female Citizens Civil Rights Committee (CCRC), led by Pearl Maddox. Starting in 1944, the CCRC conducted sit-ins at the segregated lunch counters of major downtown department stores, including Stix, Baer & Fuller, Famous-Barr, and Scruggs-Vandervoort-Barney. These courageous actions, predating many of the more nationally recognized sit-ins of the later Civil Rights Movement, gradually led to these establishments opening their dining facilities to African American patrons.

Local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League were also vital in the fight against racial injustice. They often collaborated with the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee to address issues such as police misconduct and, critically, segregated housing. The St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee notably supported the landmark Shelley v. Kraemer case, which originated in St. Louis and challenged racially restrictive covenants in housing deeds. The Supreme Court’s 1948 ruling in this case declared such covenants legally unenforceable. These varied actions demonstrate that St. Louis was a fertile ground for early and significant grassroots efforts to dismantle segregation and discrimination.

Labor After the War

The end of World War II brought new dynamics to the labor front. Nationally, the years 1945-1946 were marked by a major wave of strikes as workers, who had often deferred wage demands during the war, sought to maintain their economic gains and improve working conditions in the peacetime economy. In 1946 alone, more than 4.5 million workers across the United States participated in strikes. This period of labor unrest contributed to a shift in public and political sentiment, culminating in the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, which placed new restrictions on union powers and limited the right to strike.

In St. Louis, an industrial city with a strong union presence, these national trends were mirrored locally. The St. Louis Labor Council, formerly the Central Trades and Labor Union, had actively supported the war effort by rallying workers and maintaining morale. In the post-war period, local unions such as the Federal Labor Union, Graphic Communications International Union, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), and the Teamsters were active, with records indicating their continued organizing and presence from 1945 and 1946 onwards.

The 1940s in St. Louis thus served as a crucible for developing and testing various civil rights strategies. The decade saw a multifaceted approach to challenging racial injustice, from direct action protests like marches and sit-ins to legal challenges against discriminatory housing and advocacy for fair employment. The fight for equal opportunities in wartime industries directly fueled these broader civil rights efforts, demonstrating the growing assertiveness of the African American community and their allies. They employed a diverse toolkit of tactics that would become hallmarks of the larger national Civil Rights Movement in the years to come.

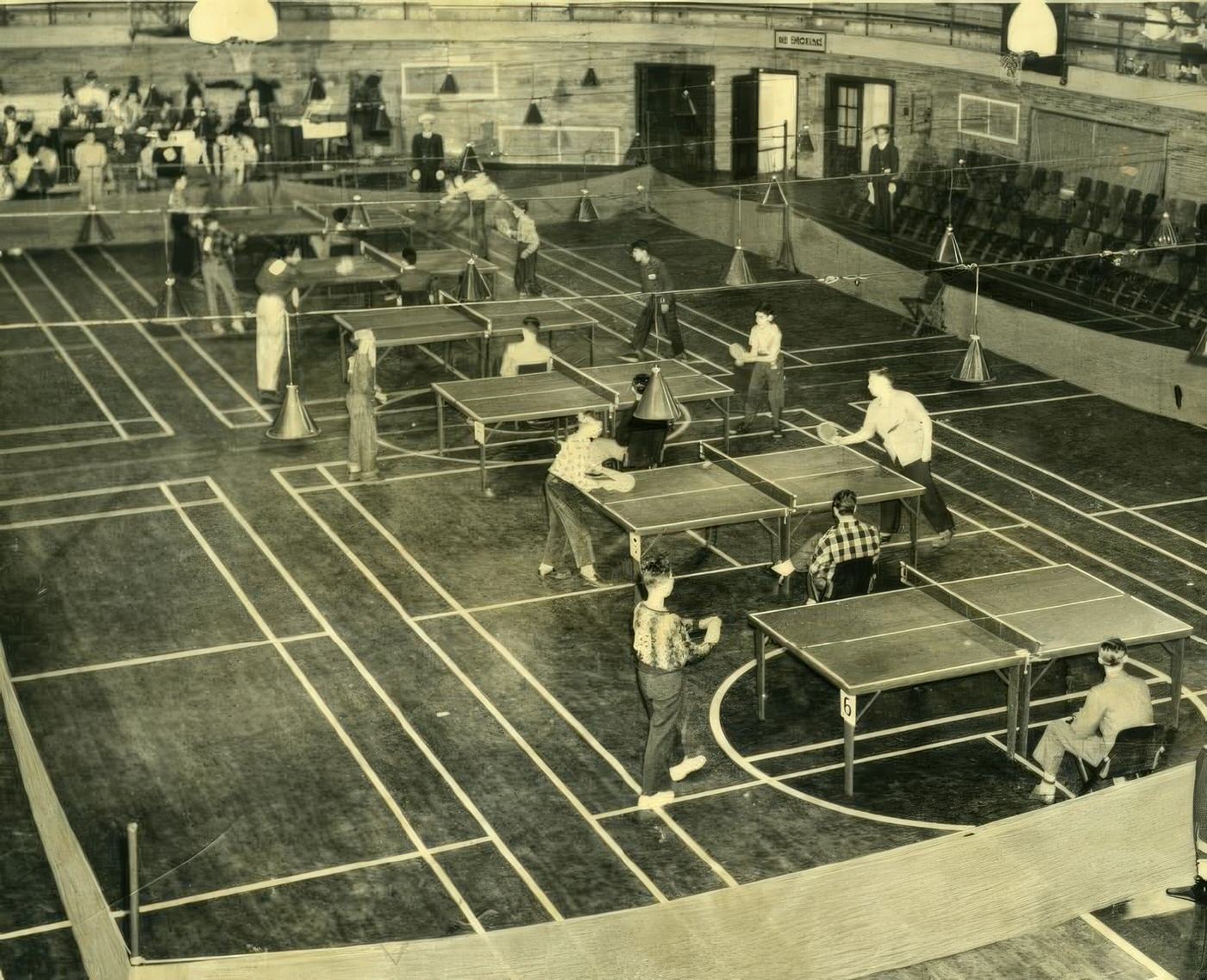

The Rhythms of City Life: Culture and Community

Amidst the backdrop of war and social change, St. Louis in the 1940s maintained a vibrant cultural and community life, offering its residents avenues for entertainment, shared experiences, and civic engagement.

Sounds of the Times: Jazz and Blues

St. Louis boasted a dynamic jazz and blues scene, with East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the river, being a particular hotbed for these musical forms. Musicians often traveled to St. Louis from New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, and riverboat performers frequently played in city clubs after their vessels docked.

Several prominent musicians were active in or emerged from the St. Louis scene during the 1940s. Trumpeters Clark Terry and a young Miles Davis, who joined Eddie Randall’s band in St. Louis in 1941, were among them. The legacy of earlier blues figures with strong St. Louis connections, such as Robert Nighthawk (McCollum), Henry Townsend, and Peetie Wheatstraw, who were highly active in the 1930s, continued to influence the musical landscape.

Notable jazz and blues clubs provided venues for both local talent and nationally renowned artists. Club Riviera, owned by influential politician and civil rights activist Jordan W. Chambers from 1944, hosted legendary performers like Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington. The Jeter-Pillars Orchestra served as the club’s house band until 1944. Peacock Alley, which opened as the Glass Bar and Gold Room on November 3, 1944, in the Hotel Midtown (later the Midland Hotel), was another key venue. DJ Spider Burks hosted a popular radio show from Peacock Alley for station KSTL. The St. Louis Argus, an African American newspaper, regularly covered the city’s bustling music scene, with articles featuring performances such as Ella Fitzgerald’s engagement at Club Riviera in 1946.

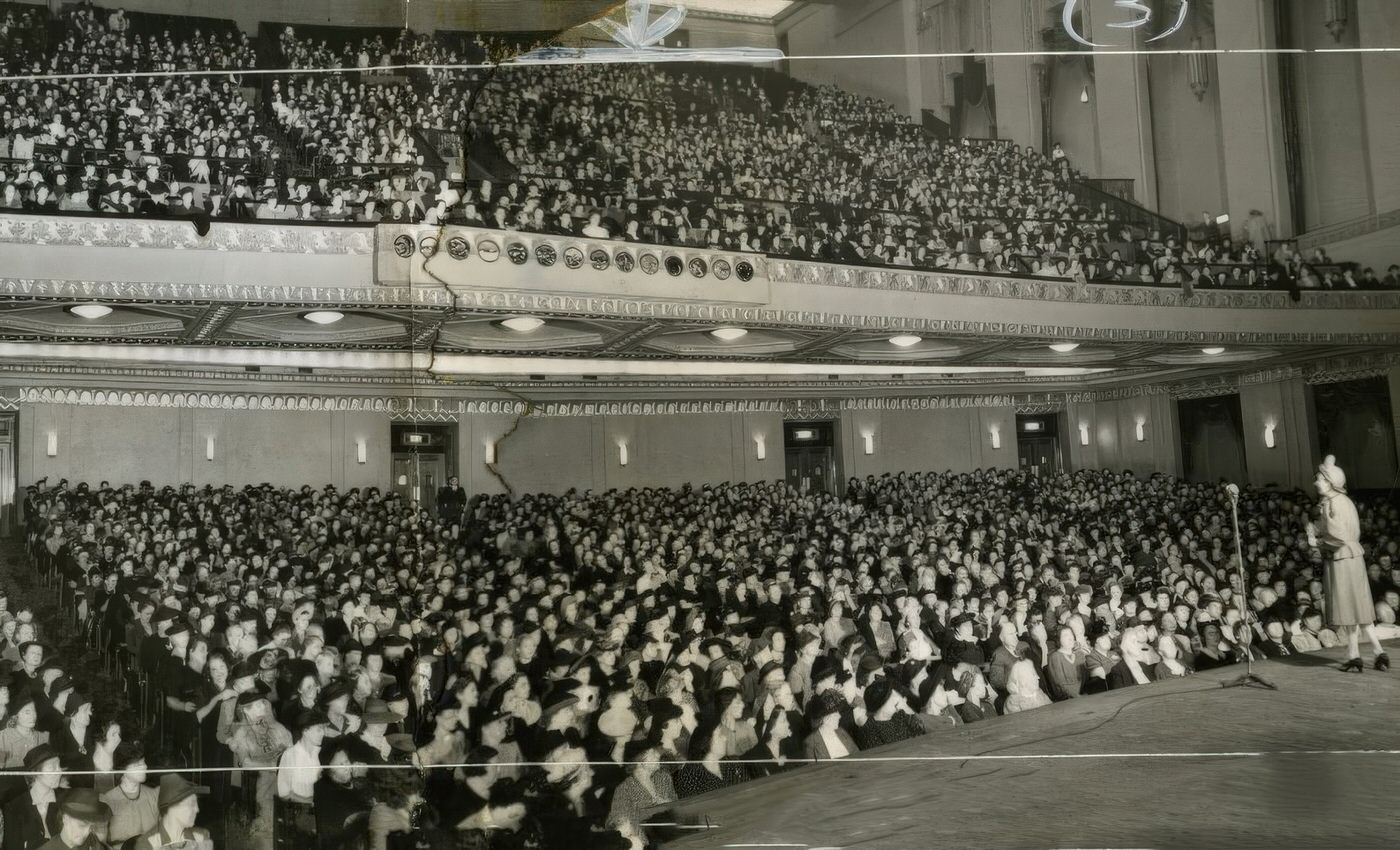

A significant cultural event was the 1944 Negro Music Festival held at Sportsman’s Park. This festival, which featured the legendary W.C. Handy (the “Father of the Blues”) and trumpeter Valaida Snow, drew an estimated 10,000 to 16,000 people and aimed to promote interracial goodwill through music.

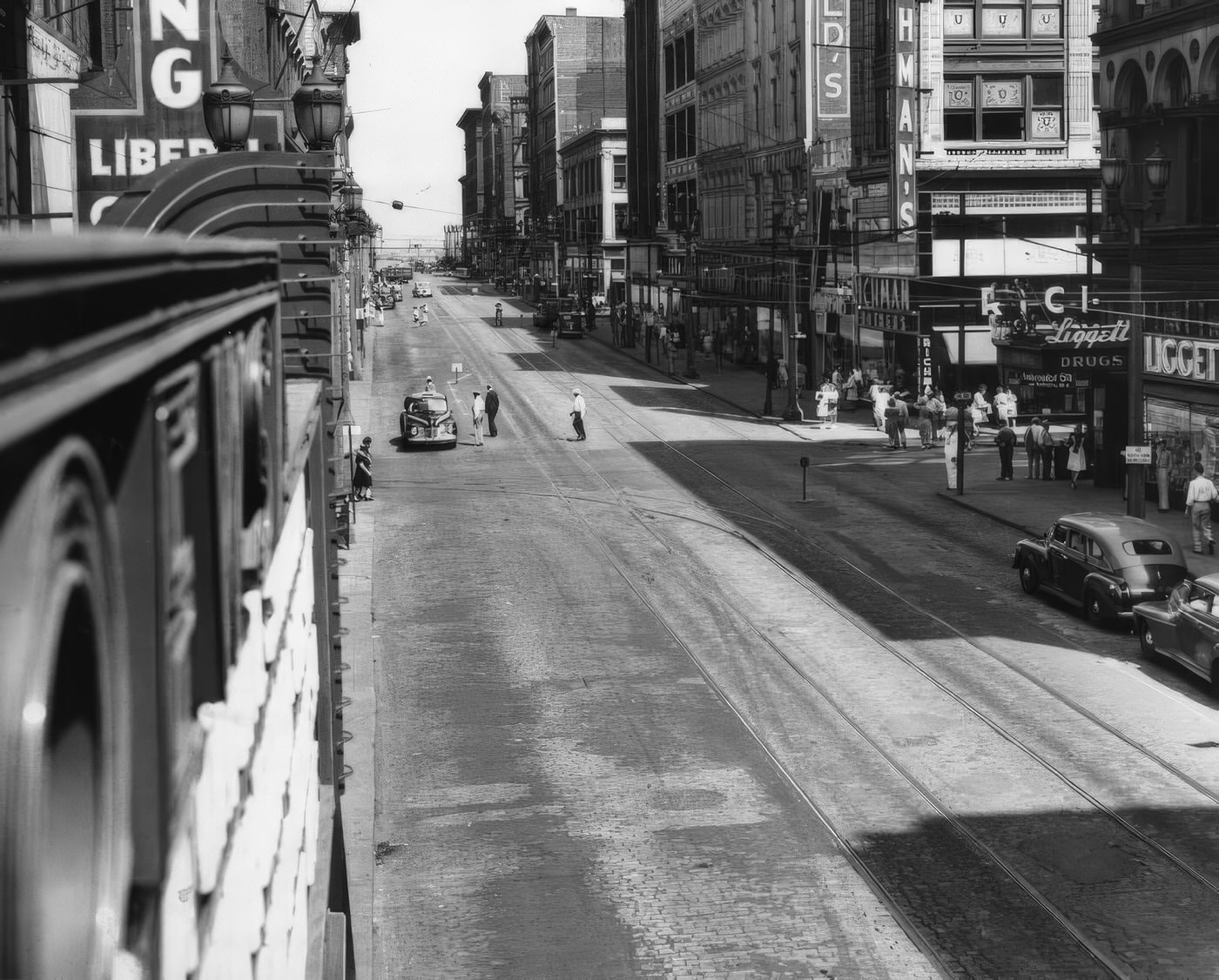

“Meet Me in St. Louis”: The Film

In 1944, the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer musical film Meet Me in St. Louis was released to great critical and commercial acclaim. The movie, starring Judy Garland, presented a romanticized and positive image of St. Louis at the turn of the 20th century, with the 1904 World’s Fair as a central theme. Several songs from the film became national hits, including “The Trolley Song,” “The Boy Next Door,” and the enduring holiday classic, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” all performed by Garland. During a time of global conflict, the film offered audiences a comforting dose of escapism and reinforced a positive image of American heartland values, with St. Louis taking center stage.

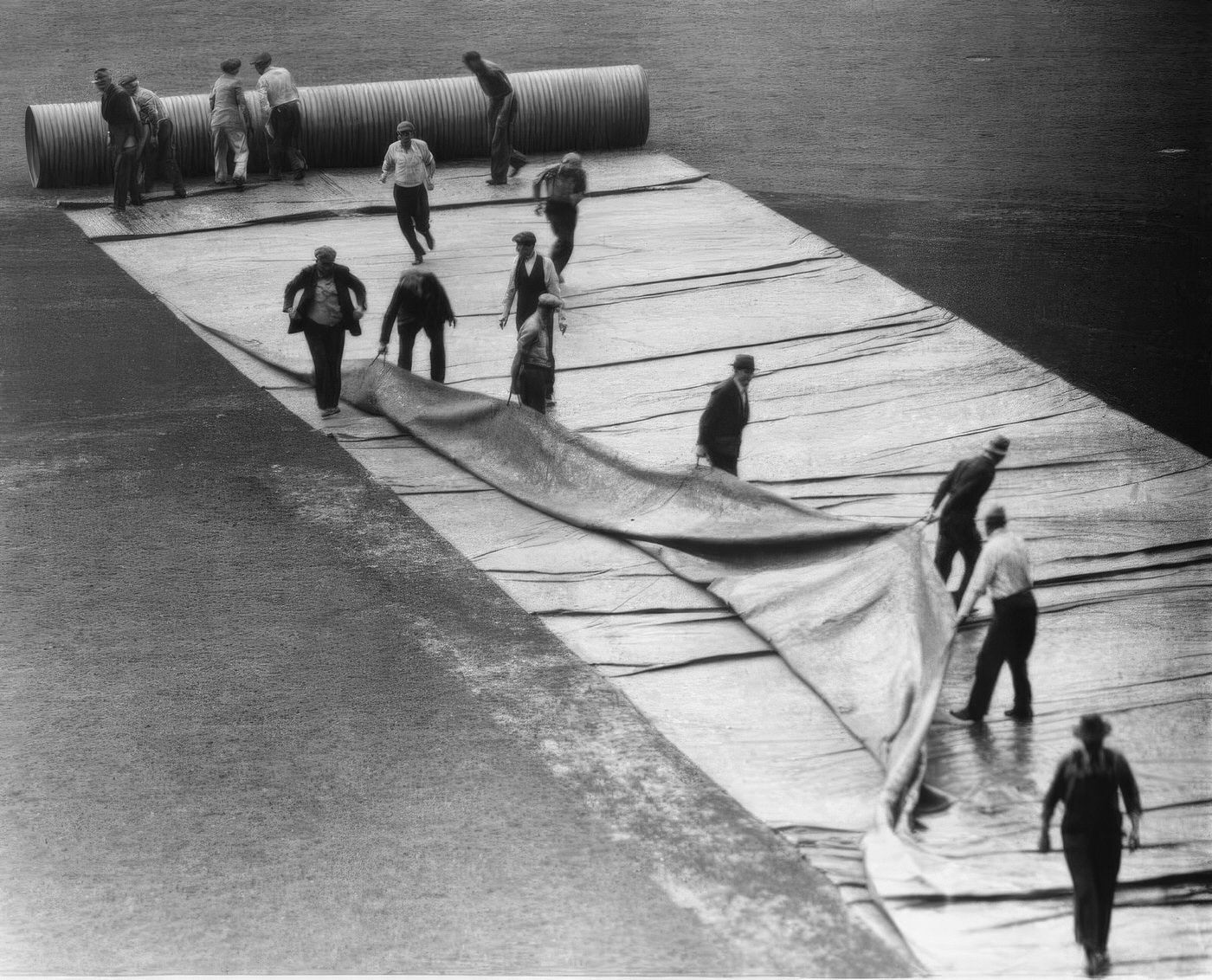

A City Divided by Baseball: The 1944 “Trolley Series”

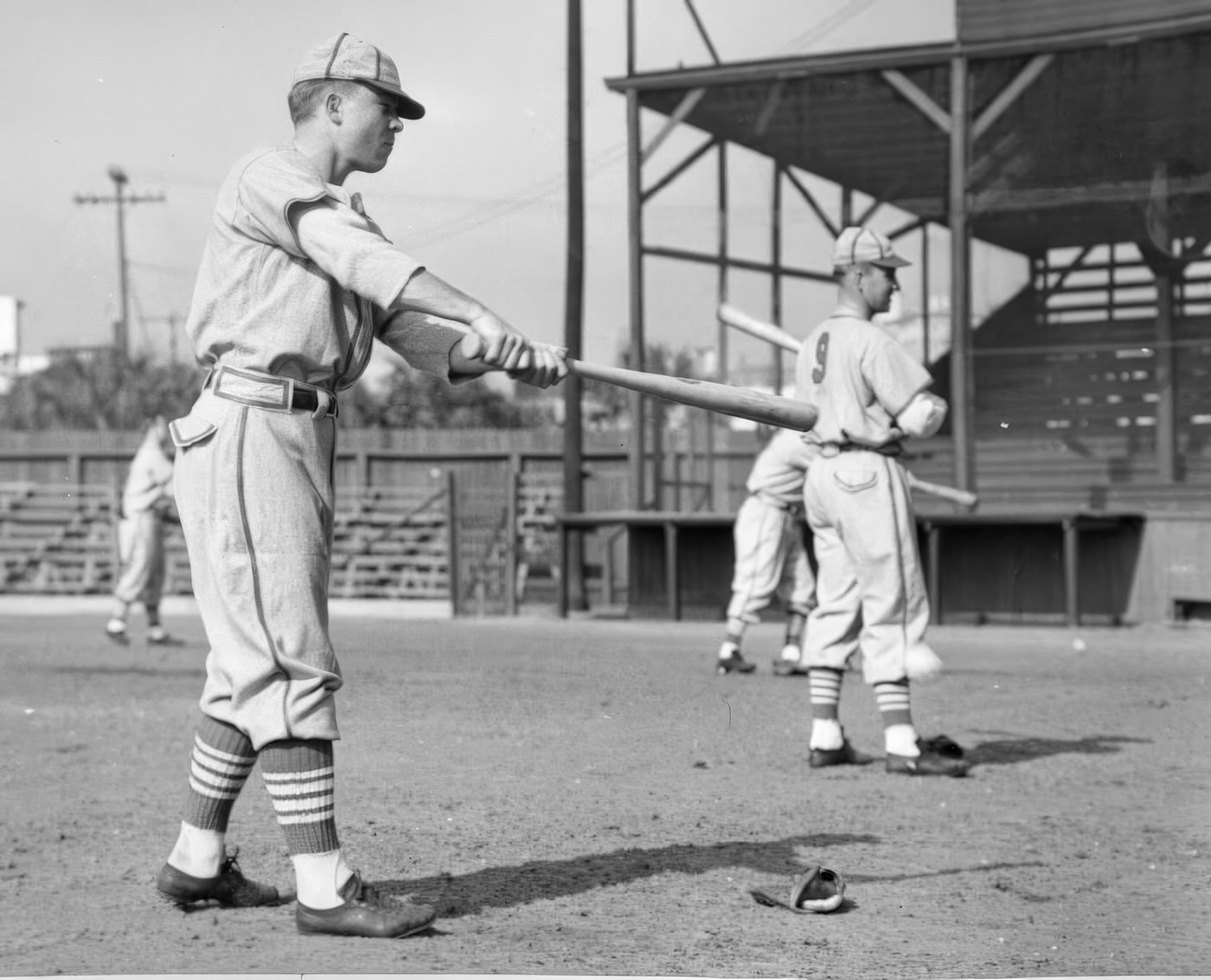

A unique and exciting event for St. Louis sports fans occurred in 1944 when both of the city’s Major League Baseball teams, the St. Louis Cardinals and the St. Louis Browns, met in the World Series. This all-St. Louis championship, played entirely at their shared home field, Sportsman’s Park, was a rare occurrence in baseball history. It was popularly dubbed the “Trolley Series” or “Streetcar Series,” reflecting the crosstown rivalry.

The Cardinals, featuring future Hall of Fame outfielder Stan Musial and National League MVP shortstop Marty Marion, were a dominant force in baseball. The Browns, on the other hand, were a historically struggling franchise that captured their only American League pennant during the war years, a time when many top players were serving in the military. The Cardinals ultimately won the hard-fought series four games to two. This unique World Series captured local and national attention, providing a significant morale boost and a source of civic pride (and intense friendly rivalry) during a challenging wartime period.

Radio Entertainment

Radio was a primary source of news and entertainment for St. Louisans in the 1940s. Popular local stations included KMOX, KSD, KXOK, WEW, and WIL. One notable program was “The Land We Live In,” which recreated historical events from the St. Louis area. The show aired on KMOX and later KSD throughout much of the decade, often performed before a live studio audience. The St. Louis Public Library maintains archival collections of radio scripts and other materials from these stations, offering a glimpse into the broadcasts that filled the airwaves.

Shaping Modern St. Louis: Urban Challenges and Changes

The 1940s were a pivotal decade for the physical and civic development of St. Louis, as the city grappled with long-standing urban challenges and began to lay the groundwork for its post-war future.

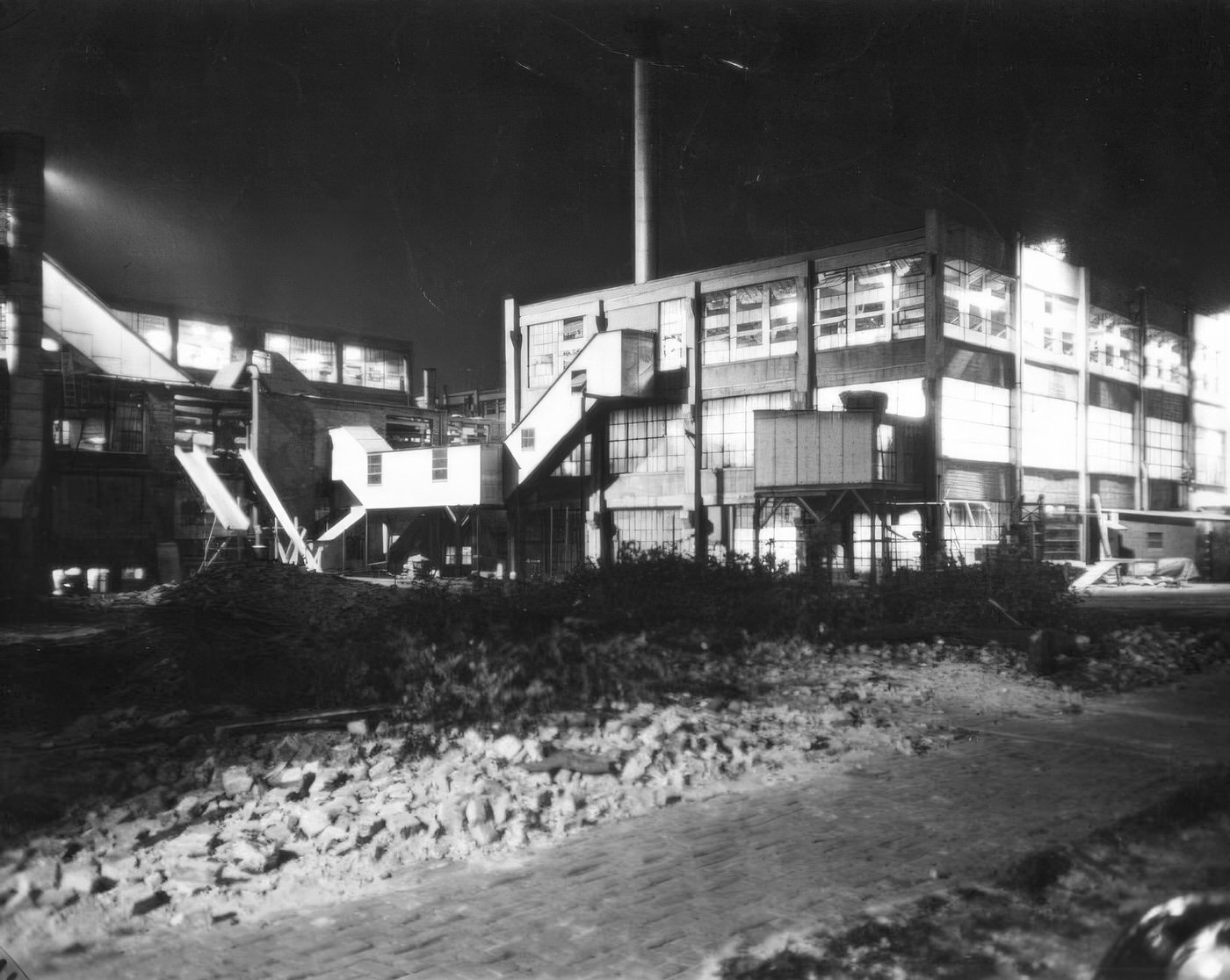

For many years, St. Louis had been plagued by severe smoke pollution, primarily caused by the widespread burning of high-sulfur bituminous (soft) coal for industrial power and residential heating. This pollution often cast a dark haze over the city. Efforts to combat this issue gained momentum under the administration of Mayor Bernard F. Dickmann (who served until 1941). He established a “citizen smoke committee” and appointed Raymond Tucker to spearhead initiatives aimed at improving air quality.

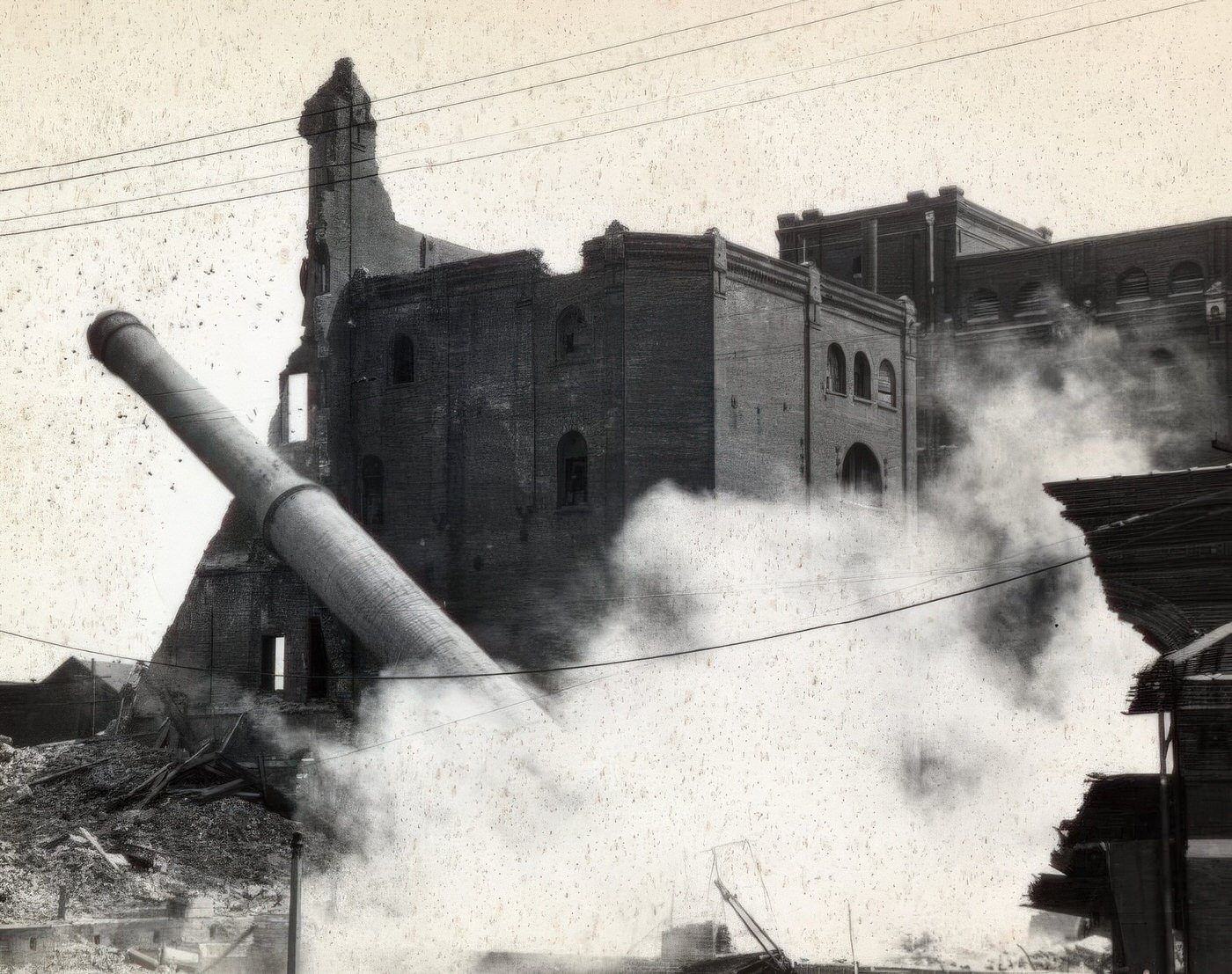

A significant step was taken in February 1937 with the passage of an anti-smoke ordinance. This law created a Division of Smoke Regulation and mandated that larger businesses switch to cleaner-burning coal. By 1938, these measures had resulted in a two-thirds reduction in smoke emissions from commercial smokestacks.

However, the problem persisted, particularly from residential heating. A dramatic turning point came on November 28, 1939, a day that became known in St. Louis as “Black Tuesday.” On this day, a severe temperature inversion trapped a thick, dark cloud of smoke over the city, plunging it into daytime darkness for several days. This alarming event served as a powerful catalyst for more stringent action. In response, the city secured supplies of cleaner semi-anthracite coal from Arkansas and enacted new, tougher smoke ordinances. These measures, combined with a public education campaign vigorously supported by newspapers like the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, led to a remarkable and lasting improvement in the city’s air quality by the early 1940s. The winter of 1940-1941 saw a dramatic drop in the hours of thick smoke pollution compared to the previous year. The Laclede Gas Company also began supplying cleaner-burning natural gas to customers starting in 1941, further contributing to the solution of the smoke problem by the late 1940s.

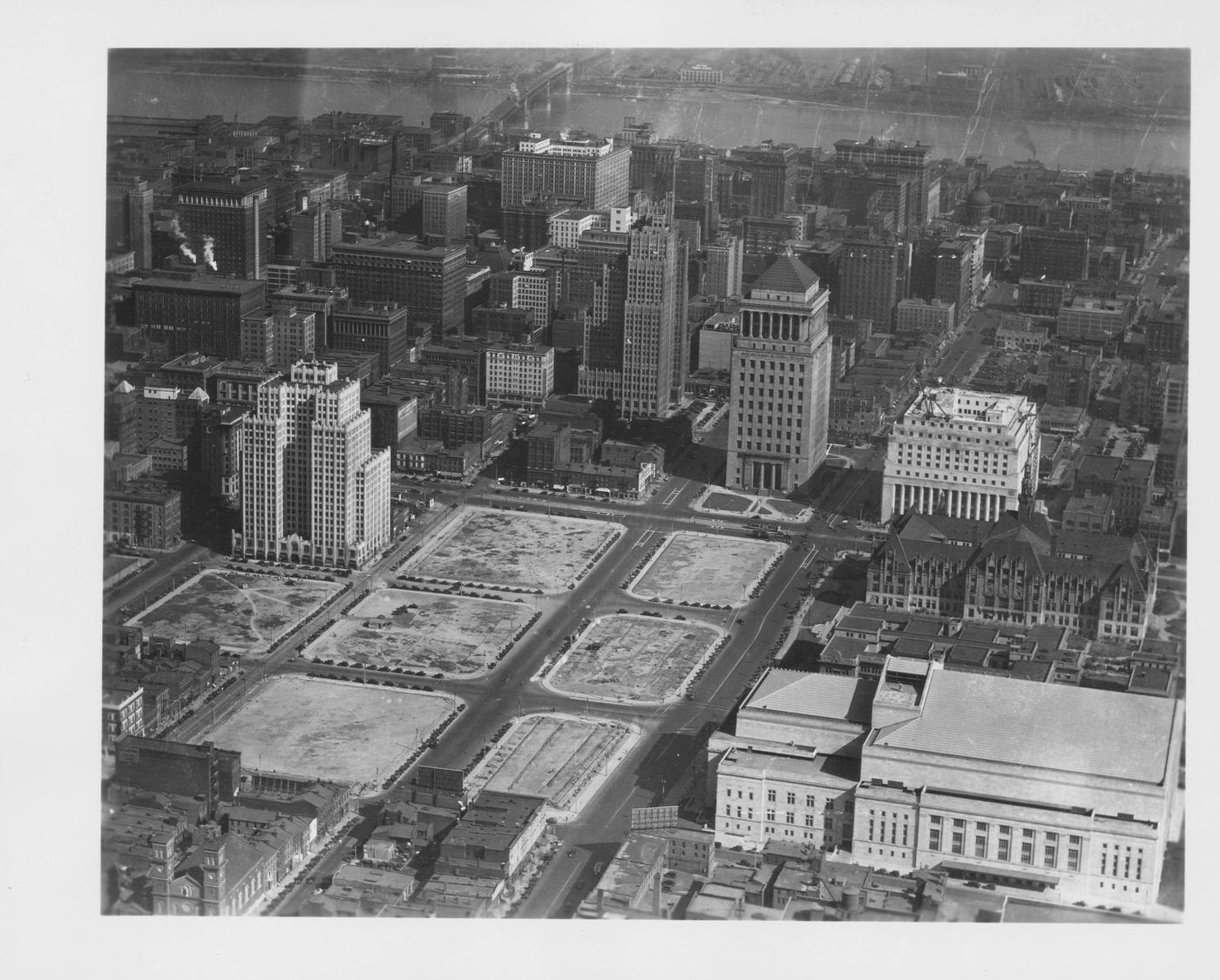

Building the Future: Public Works and City Planning

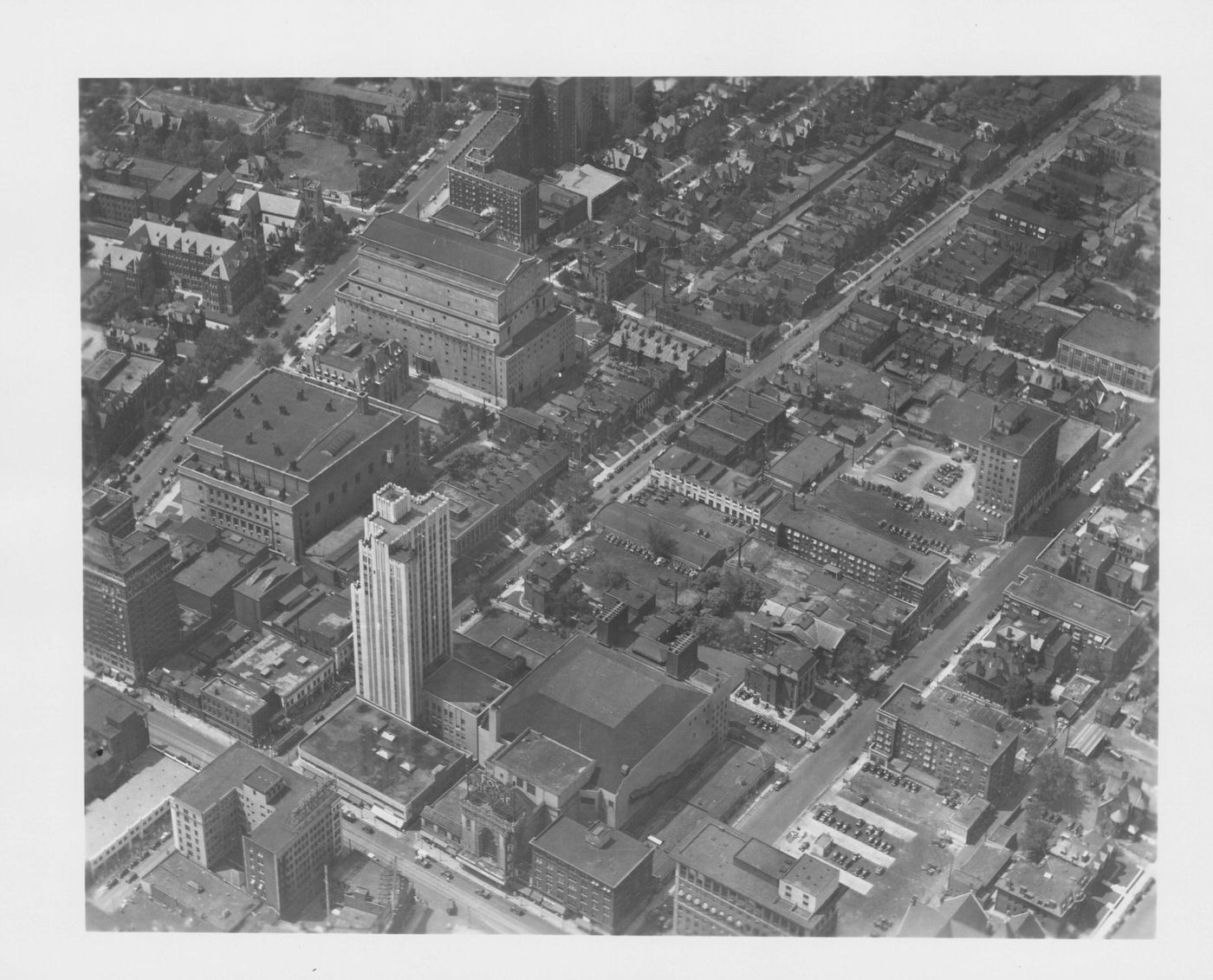

The 1940s also saw continued efforts to shape the physical landscape of St. Louis through public works and city planning. Harland Bartholomew served as the city’s influential planner until 1950. His planning philosophy encompassed urban renewal projects and a focus on accommodating the automobile. Controversially, Bartholomew also viewed zoning as a tool to enforce racial segregation in housing and neighborhood development.

One of the most significant long-term projects initiated during this era was the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, which would later feature the Gateway Arch. The initial steps, including land clearance on the downtown riverfront, were taken under Mayor Dickmann’s administration in the late 1930s and continued into the early 1940s. Many Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects completed in the late 1930s, such as the Laundry Building at the Old City Hospital complex (finished in 1940), continued to serve the city throughout the 1940s. The post-war period also saw the beginnings of planning for new highway systems, infrastructure that would profoundly reshape the city and facilitate suburban growth in the following decades.

Crime and Law Enforcement

During World War II, the FBI’s St. Louis field office saw its responsibilities and size grow substantially. Its agents focused on national security matters, conducted security checks for vital war plants, and investigated allegations of sabotage. Beyond federal concerns, local crime remained a part of city life. The 1942 lynching of Cleo Wright in Sikeston, Missouri, though outside St. Louis, drew the attention and investigative efforts of the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee and the NAACP. Records from the St. Louis Urban League from the late 1930s and early 1940s also refer to “gangster bombings,” indicating ongoing concerns about organized criminal activity.

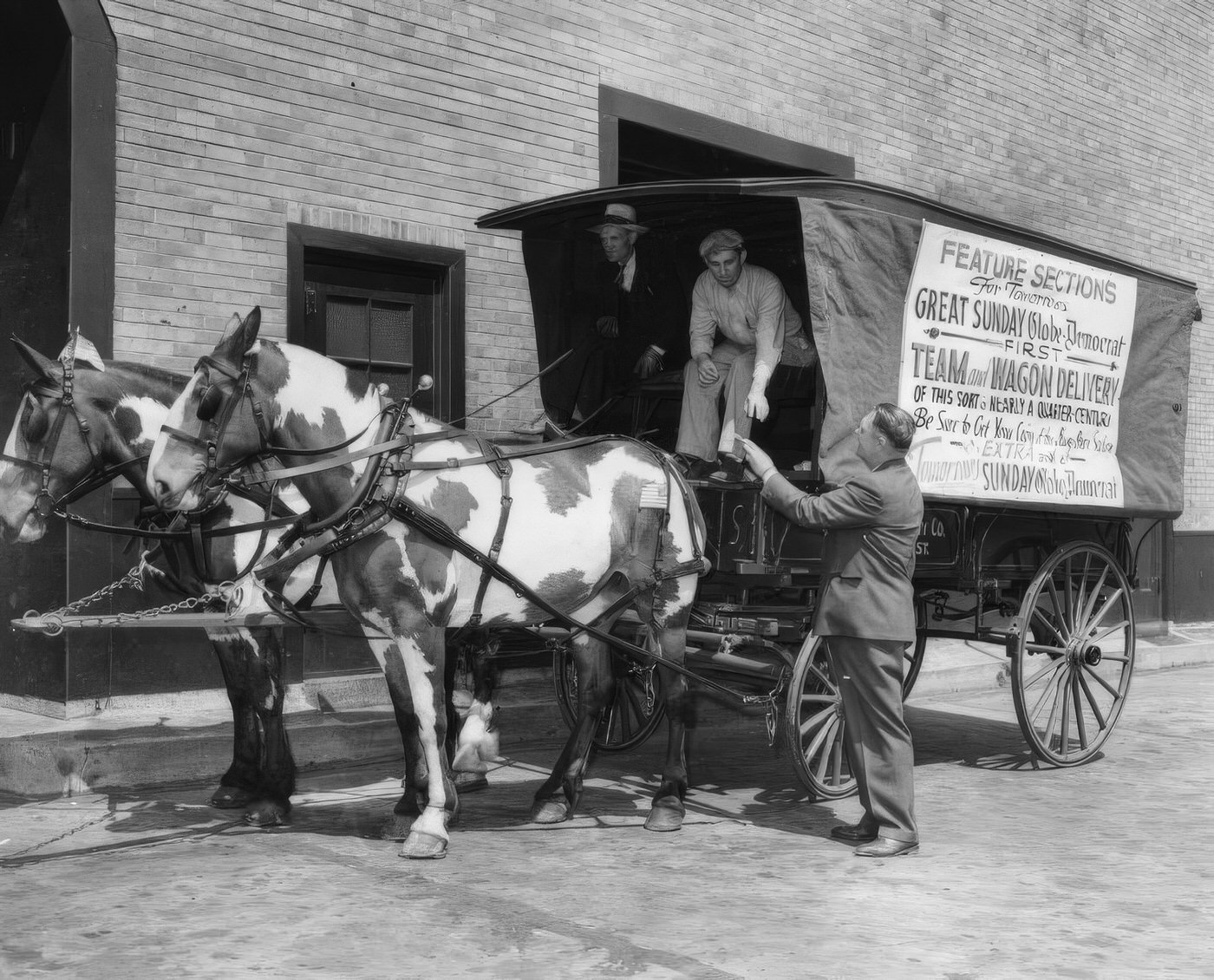

The city’s events, including crime, were extensively covered by a vibrant local press. Major daily newspapers included the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. The St. Louis Star-Times served as another evening paper. The African American community was served by the St. Louis Argus. Law enforcement agencies dealt with a spectrum of issues, from war-related security threats to everyday local crime, all under the public eye of these newspapers.

The urban development and civic improvements of the 1940s presented a paradox. On one hand, St. Louis made tangible progress in areas like air quality and began ambitious projects like the riverfront memorial. These efforts aimed to modernize the city and enhance the quality of life for its citizens. On the other hand, the prevailing planning philosophies of the time, notably those advanced by figures like Harland Bartholomew, sometimes incorporated racial segregation as an explicit component of urban design. Thus, while the city was advancing in terms of its physical infrastructure and environmental health, these developments were often intertwined with policies and practices that reinforced or even deepened racial and social divisions, particularly in housing and neighborhood development.

Image Credits: The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Library of Congress, Wikimedia,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know