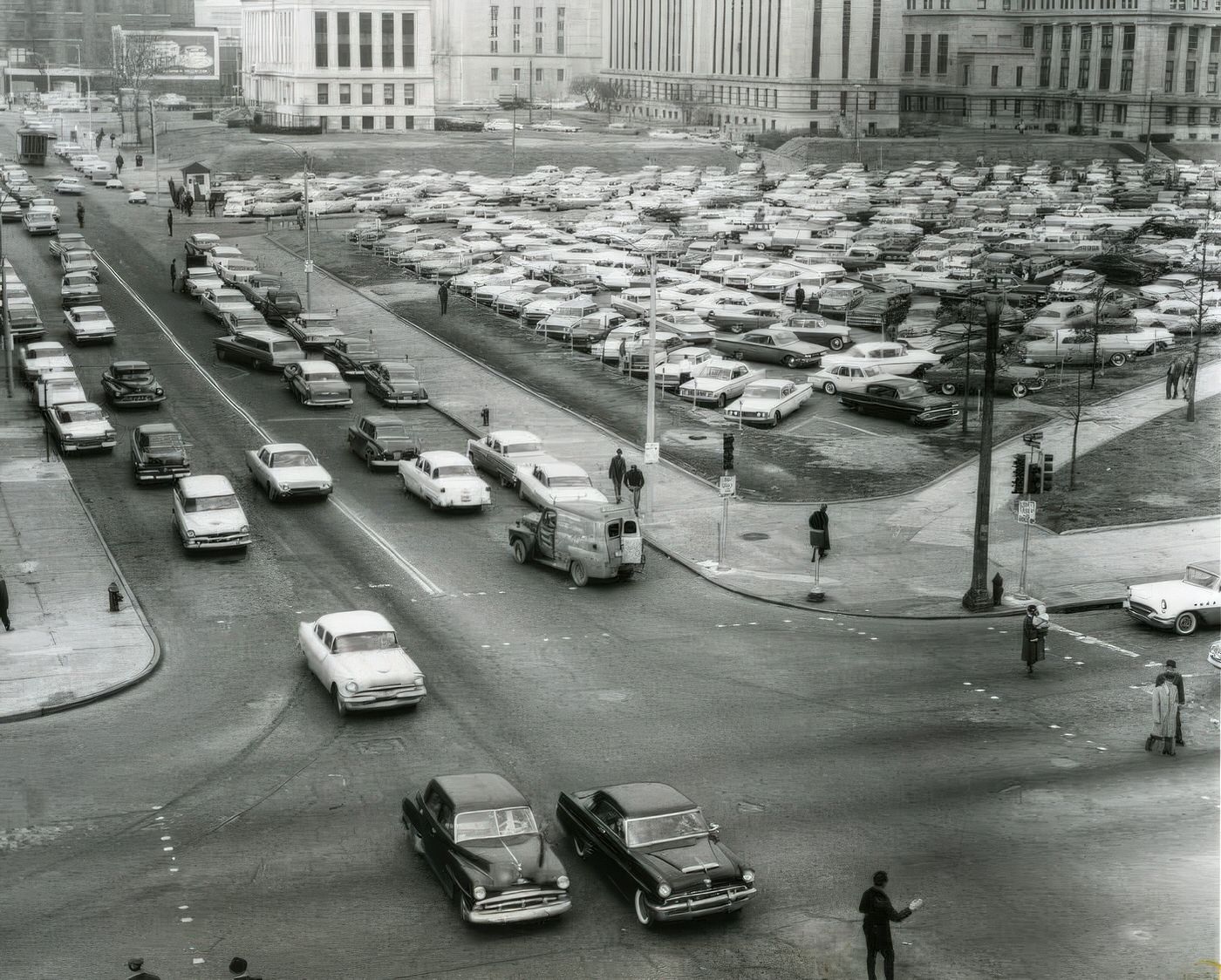

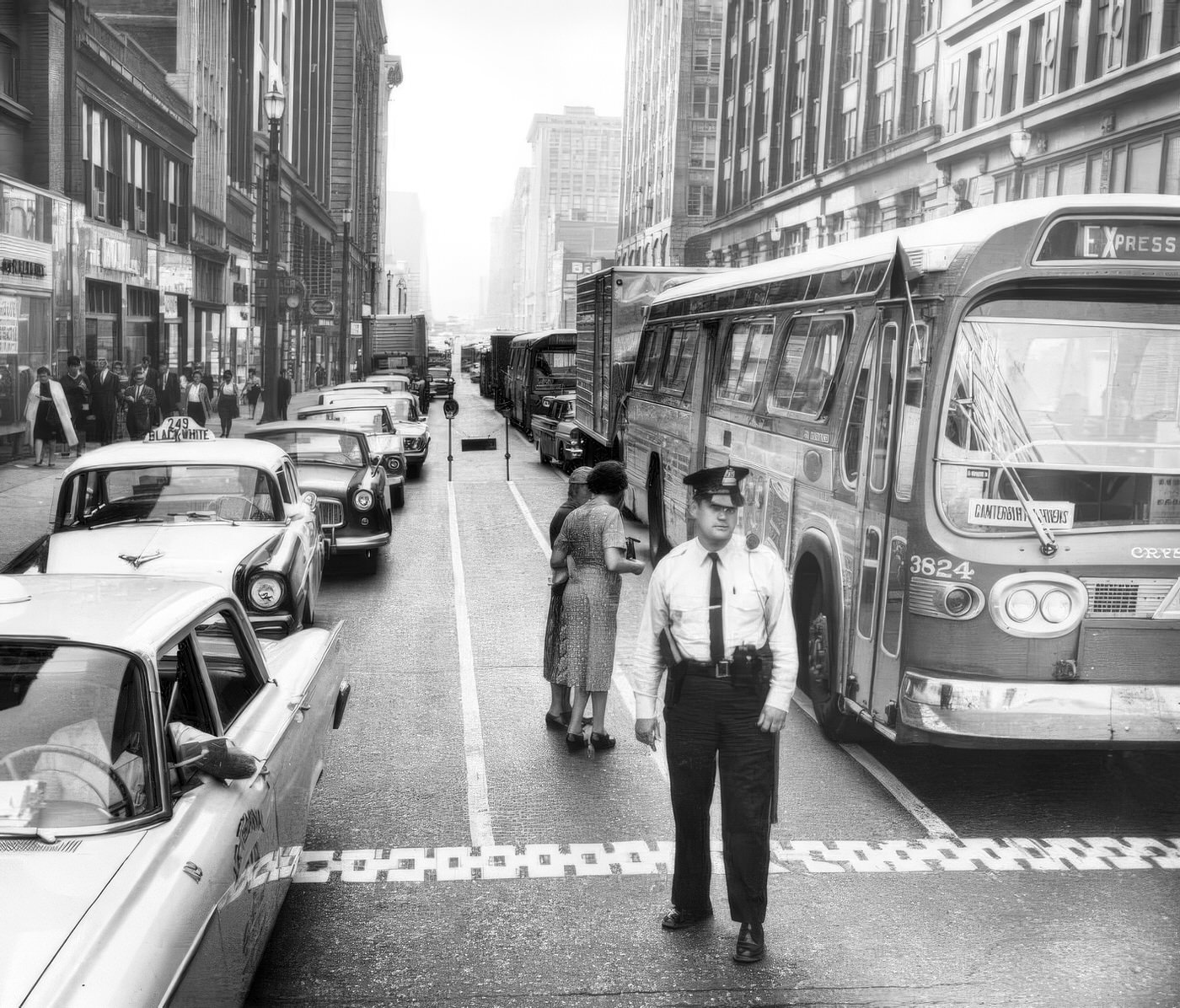

St. Louis entered the 1960s as a significant American city, home to 750,026 people according to the 1960 census. This figure, however, represented a city on the cusp of major demographic shifts. While the broader St. Louis metropolitan area was expanding, this growth was largely concentrated in its suburban rings. The central city itself was beginning to experience a population decline, a trend that would accelerate throughout the decade. This dynamic created an undercurrent of tension between the urban core and its burgeoning suburbs, particularly concerning resources and the changing face of the city’s population. Nationally, central cities were losing their share of the metropolitan population, and St. Louis was notable for experiencing one of the sharpest drops among large urban centers.

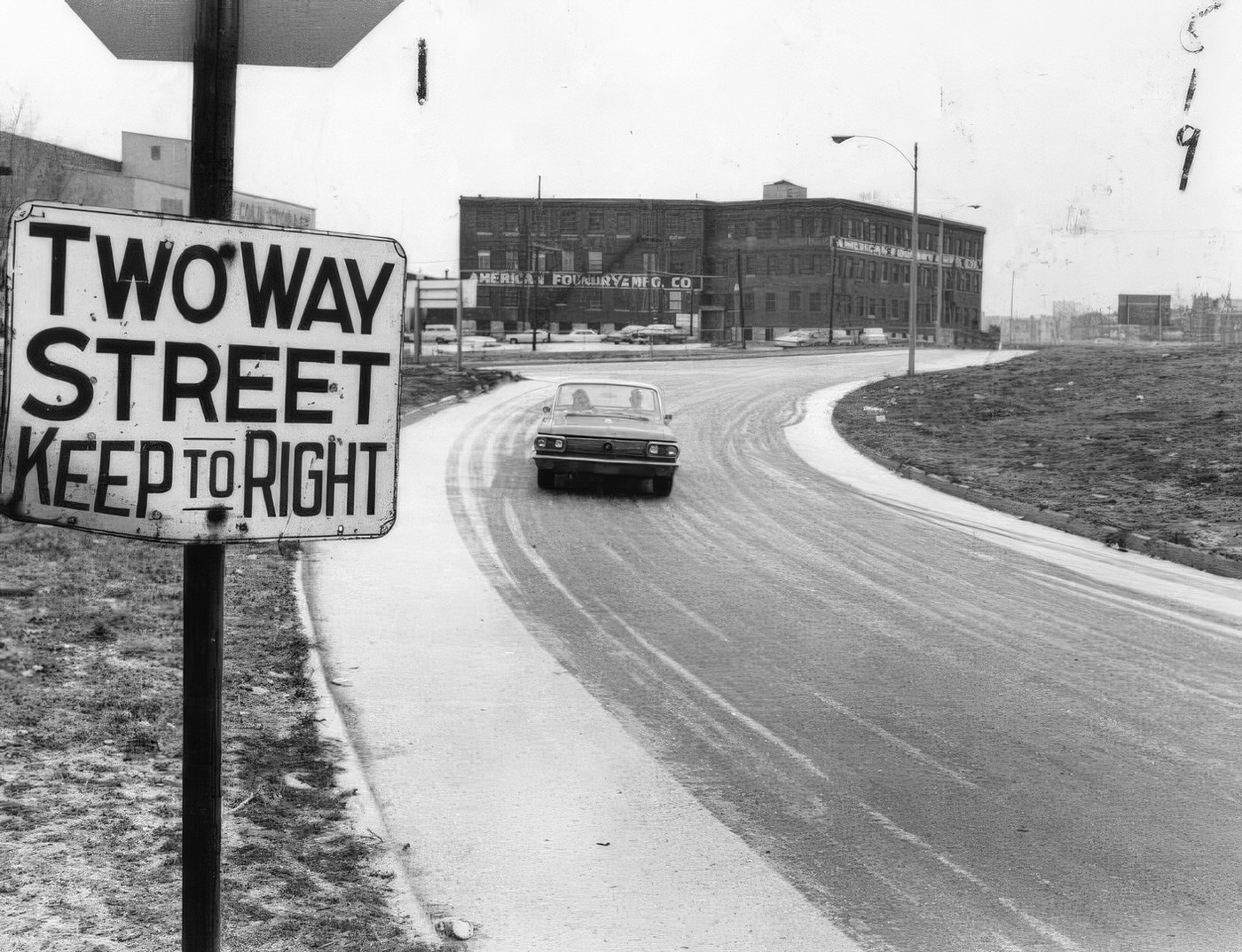

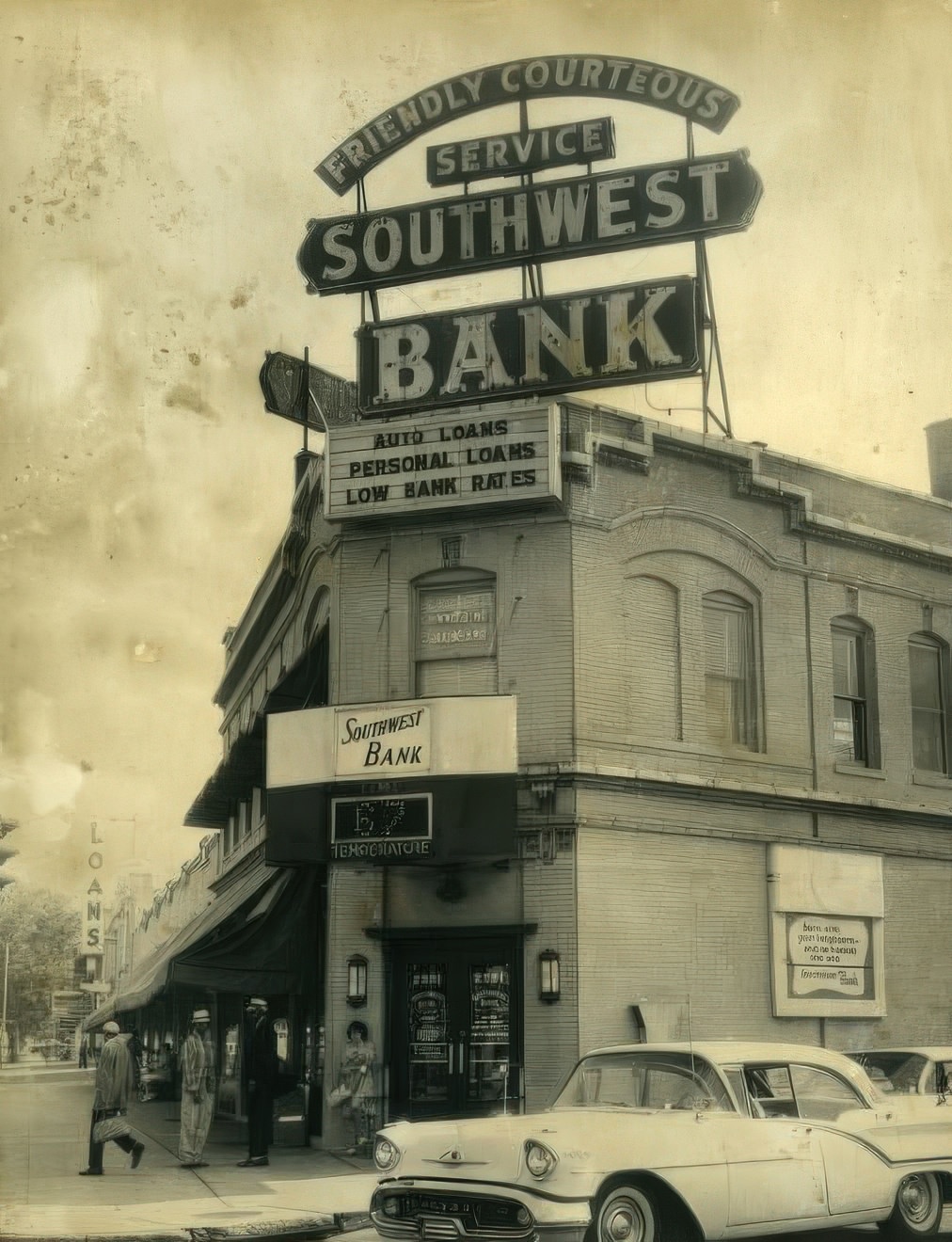

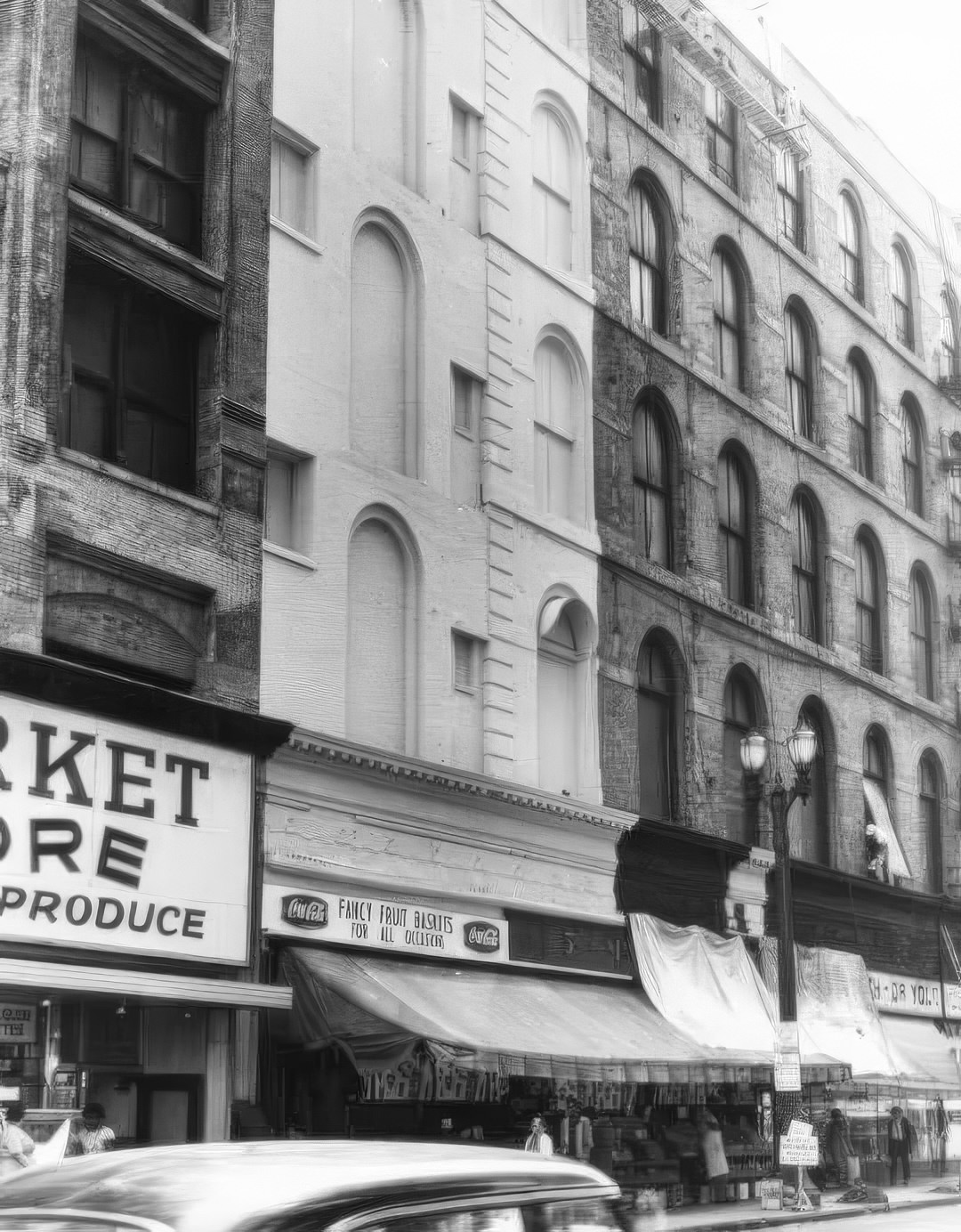

The city’s economy had long been anchored by robust industrial pillars. Brewing, with the massive Anheuser-Busch company as a cornerstone, was a historic and economically vital industry, providing substantial employment. Alongside brewing, St. Louis had a strong manufacturing base encompassing sectors such as steel, chemicals, automobiles, and clothing. The Washington Avenue area, for instance, was a well-known center for garment and shoe manufacturing. However, these established industries were encountering new and formidable pressures as the 1960s unfolded. The city’s economic structure, characterized by an overspecialization in a few heavy industries, was described as “brittle”. This reliance on sectors vulnerable to national and global shifts meant St. Louis was not ideally positioned to weather the deindustrialization trends that began to take hold, foreshadowing future job losses and economic difficulties that would inevitably intersect with pressing social and civil rights issues.

Landmarks, Living Spaces, and Population Movements

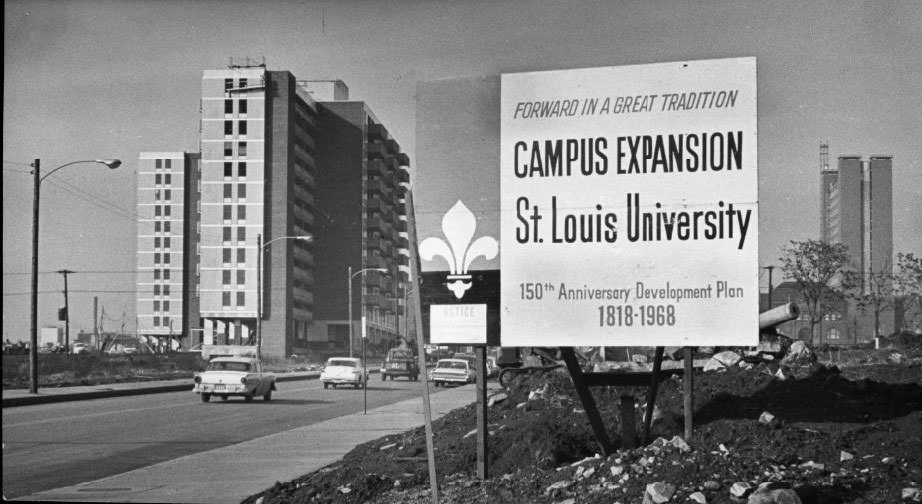

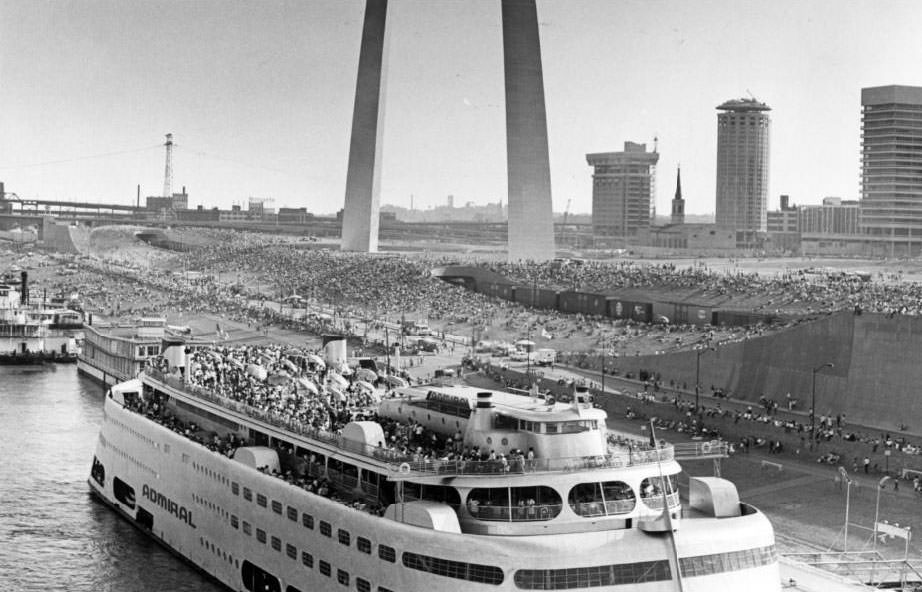

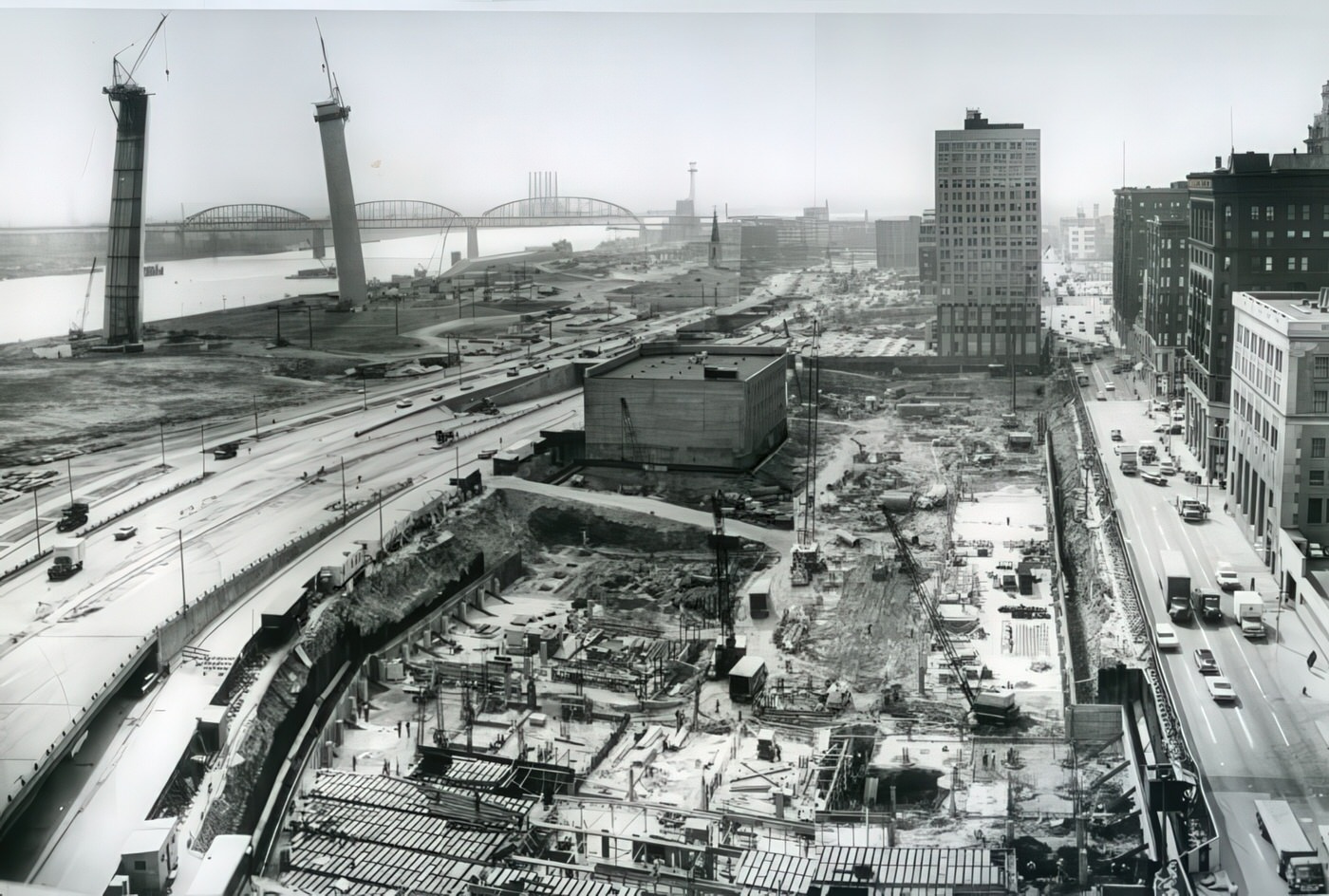

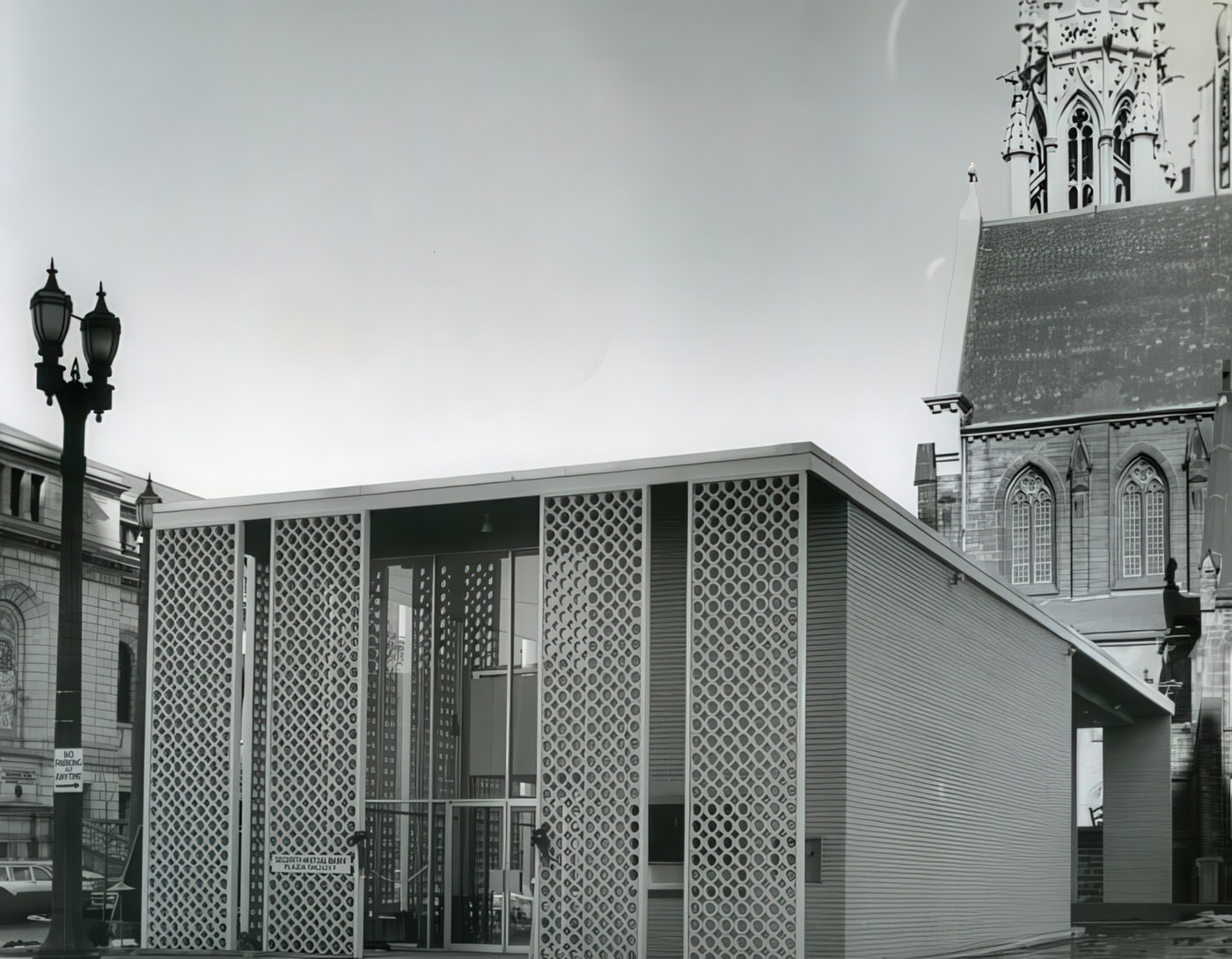

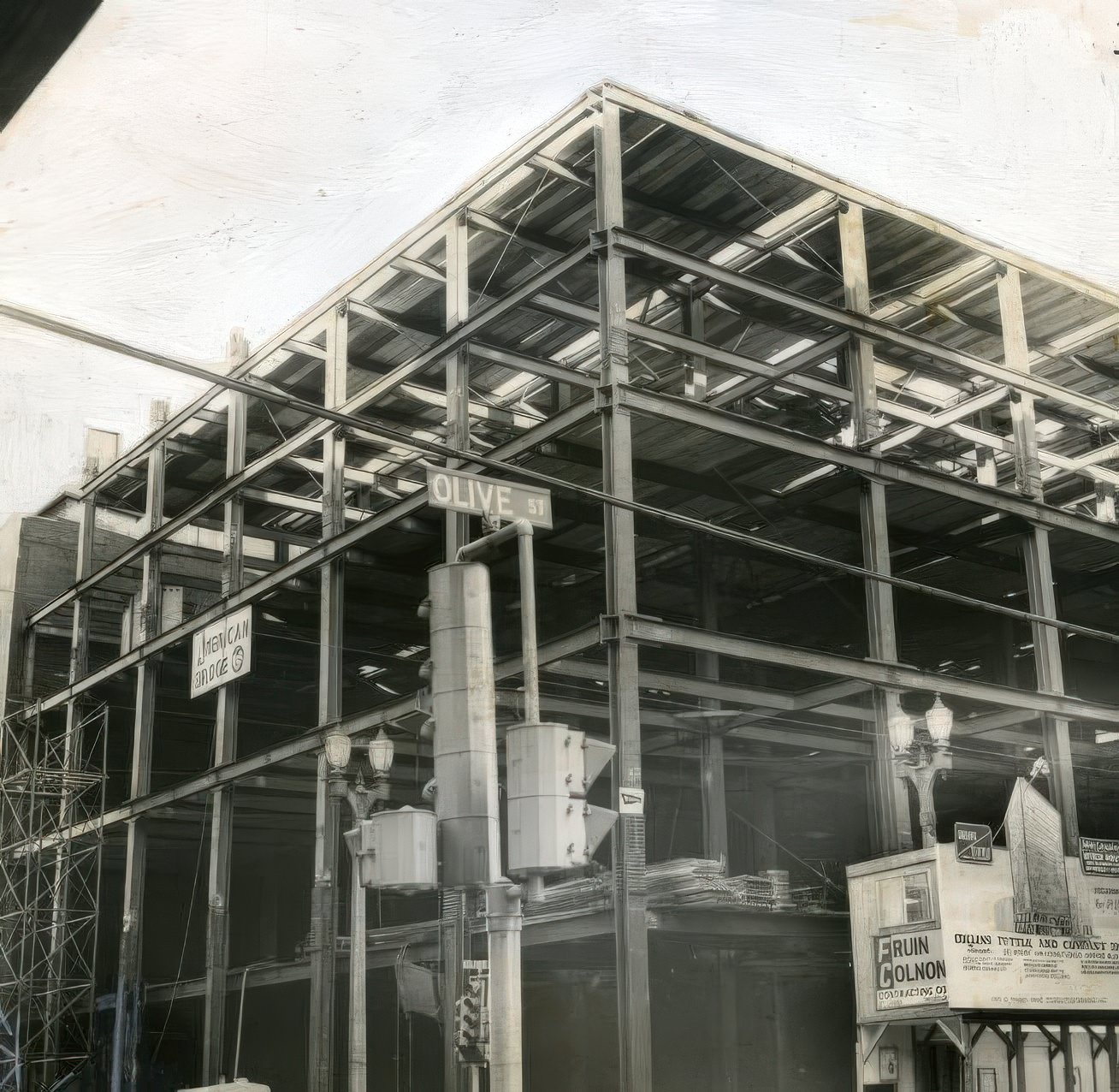

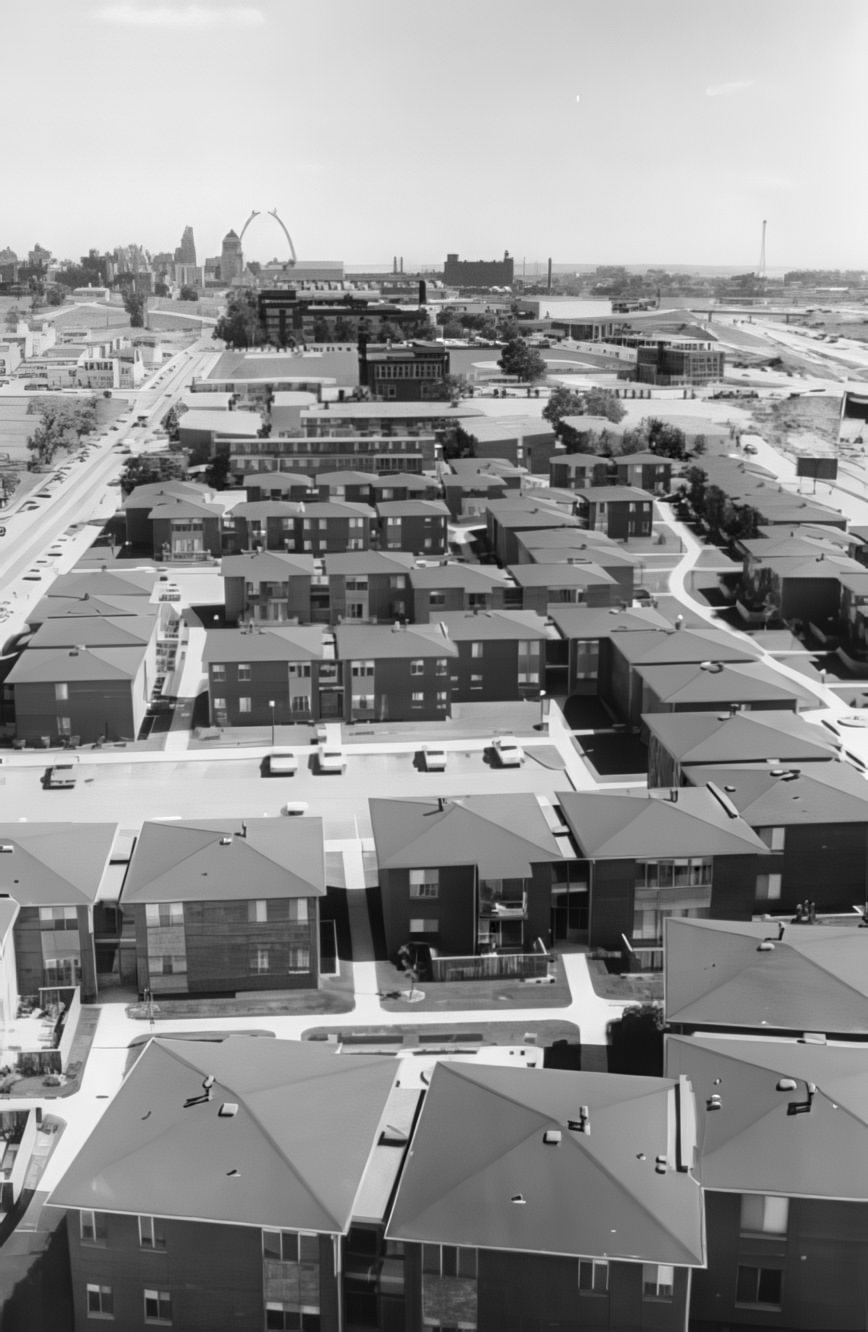

The physical and demographic landscape of St. Louis underwent dramatic transformations during the 1960s. One of the most visible projects was the construction of the Gateway Arch. Designed by architect Eero Saarinen as a monument to westward expansion, work on this iconic structure commenced in the early part of the decade, with sources citing either 1961 or 1963 as the start date. The massive, stainless steel edifice reached completion when its final section was intricately placed on October 28, 1965. The project’s cost was substantial, estimated between $13.4 million and $15 million. A significant portion of this funding was secured through local efforts; Mayor Alfonso J. Cervantes played a key role in passing a $2 million bond issue specifically for the Arch’s completion, a sum that was vital for leveraging an additional $6 million in federal aid.

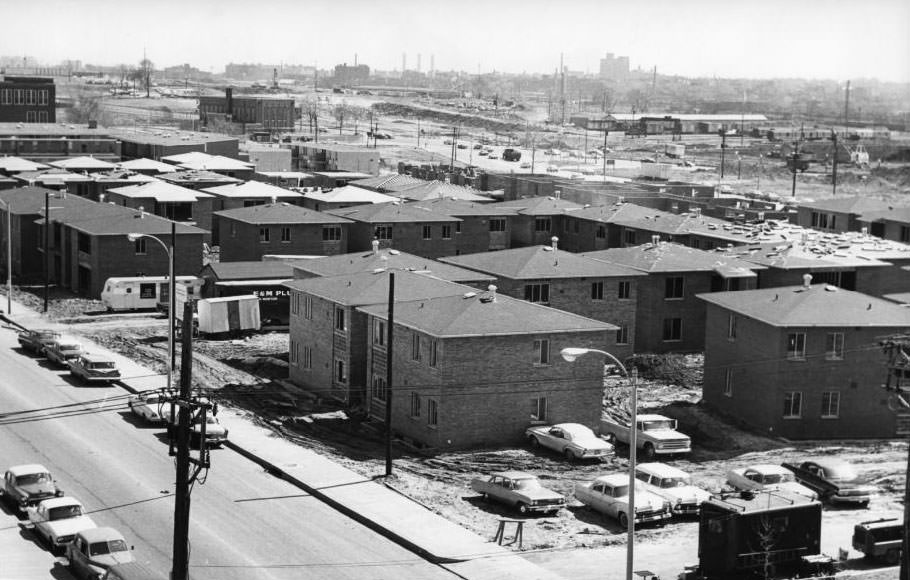

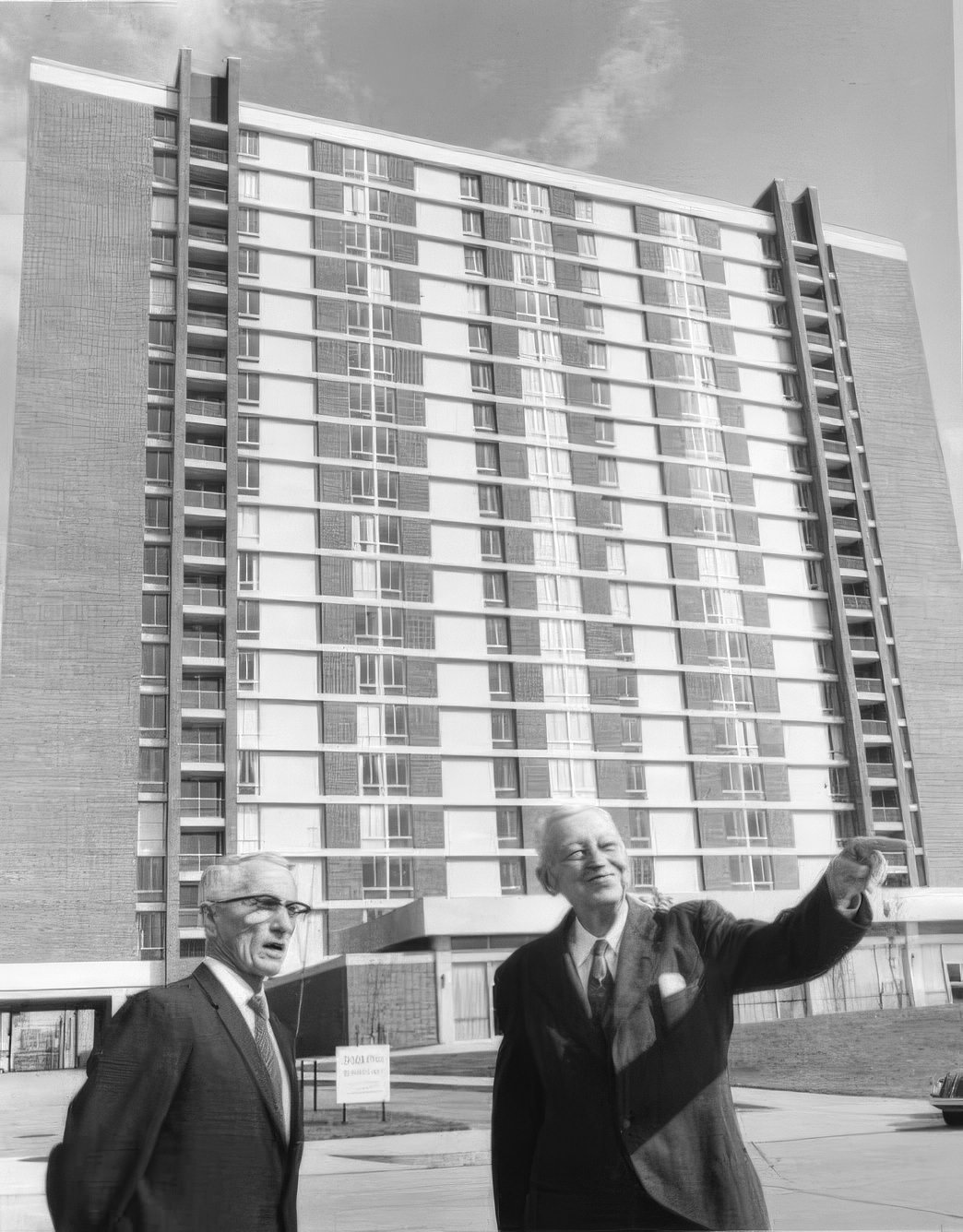

While the Arch rose as a symbol of civic pride and ambition, another major housing development, Pruitt-Igoe, was heading in a starkly different direction. First occupied in 1954, the complex consisted of 33 high-rise buildings and was initially hailed as an improvement over the slum housing it replaced. However, by the 1960s, Pruitt-Igoe was rapidly deteriorating. Poor maintenance, escalating crime rates, and widespread vandalism plagued the development. Following a 1955 Supreme Court decision that banned overt segregation in federally funded housing projects, and as white residents increasingly moved to the suburbs, Pruitt-Igoe’s population became overwhelmingly African American. It housed many of the city’s poorest families, with nearly 10,000 tenants by 1965. The project’s decline was so severe that it became a national symbol of the urban crisis and the perceived failures of large-scale public housing policies. The simultaneous construction of the gleaming Gateway Arch and the visible decay of Pruitt-Igoe painted a picture of a city with dual realities: one of monumental achievement and national symbolism, and another of deepening social crisis and urban despair. This contrast underscored an uneven allocation of resources and civic attention.

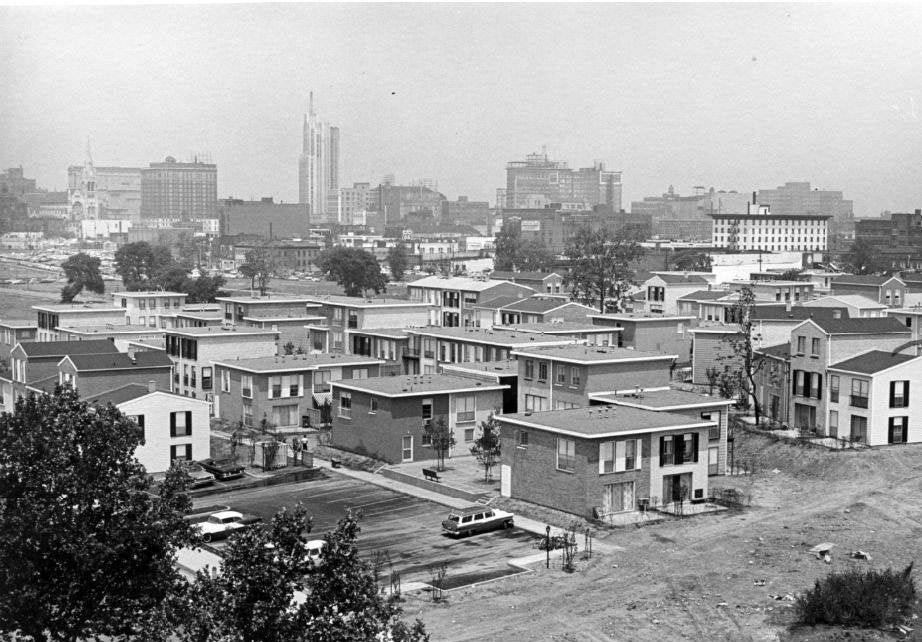

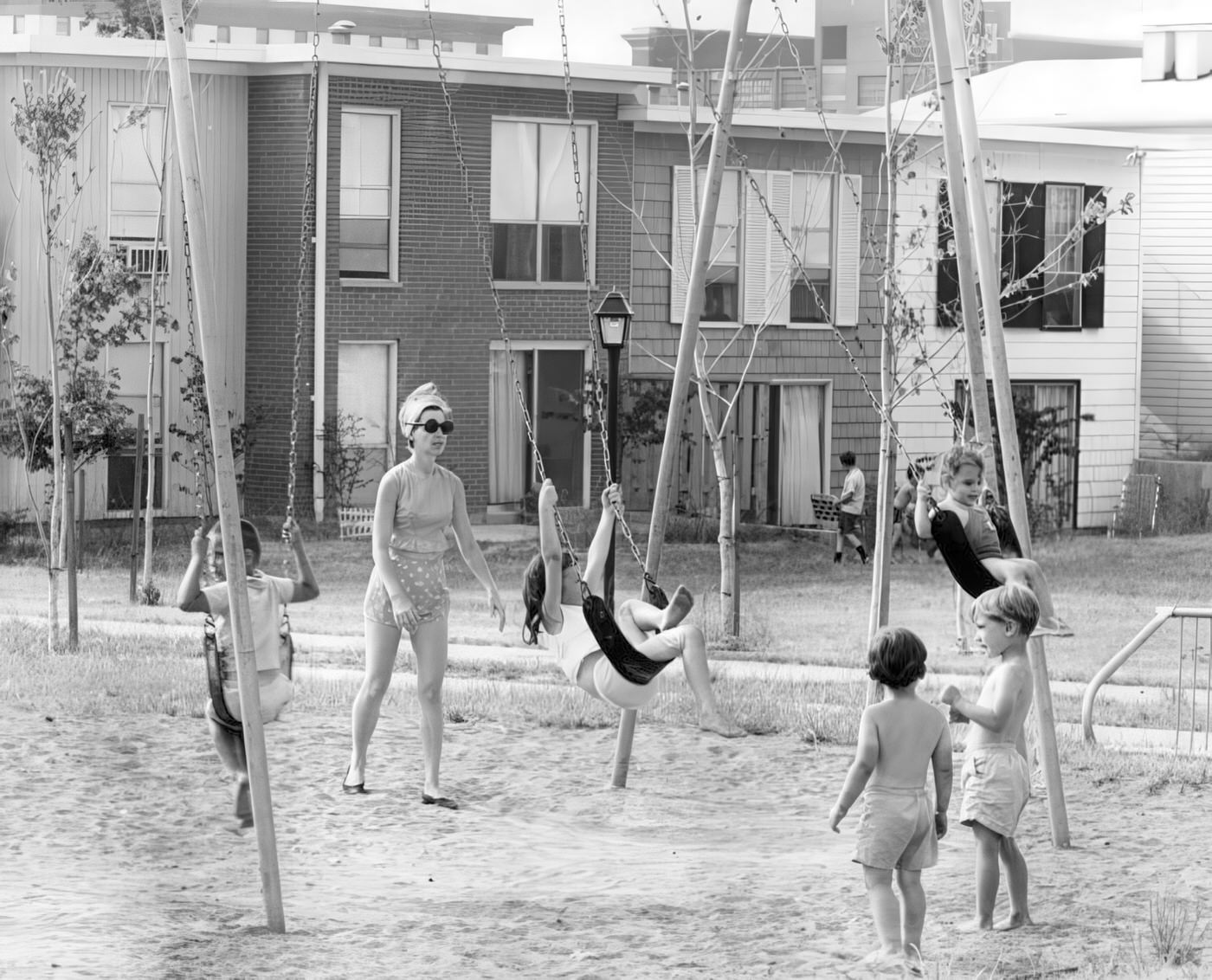

In response to the challenges of urban living and the recognized shortcomings of projects like Pruitt-Igoe, alternative approaches to housing were explored. LaClede Town, developed in the cleared Mill Creek Valley area, partially opened its doors in 1965. Designed by Chloethiel Woodard Smith, it embodied a different philosophy, aiming to create an “urban utopia” with an emphasis on community, integrated social spaces, and resident diversity. LaClede Town attracted a mix of low- and middle-income individuals, including artists, musicians, and academics. It was notably racially integrated, with a population that, at its peak, was reported as 60-70% white and 20-30% Black. These varied approaches to urban residential development reflected a period of intense experimentation and uncertainty in urban planning, driven by the urgent need to retain a diverse population and address the failures of past models.

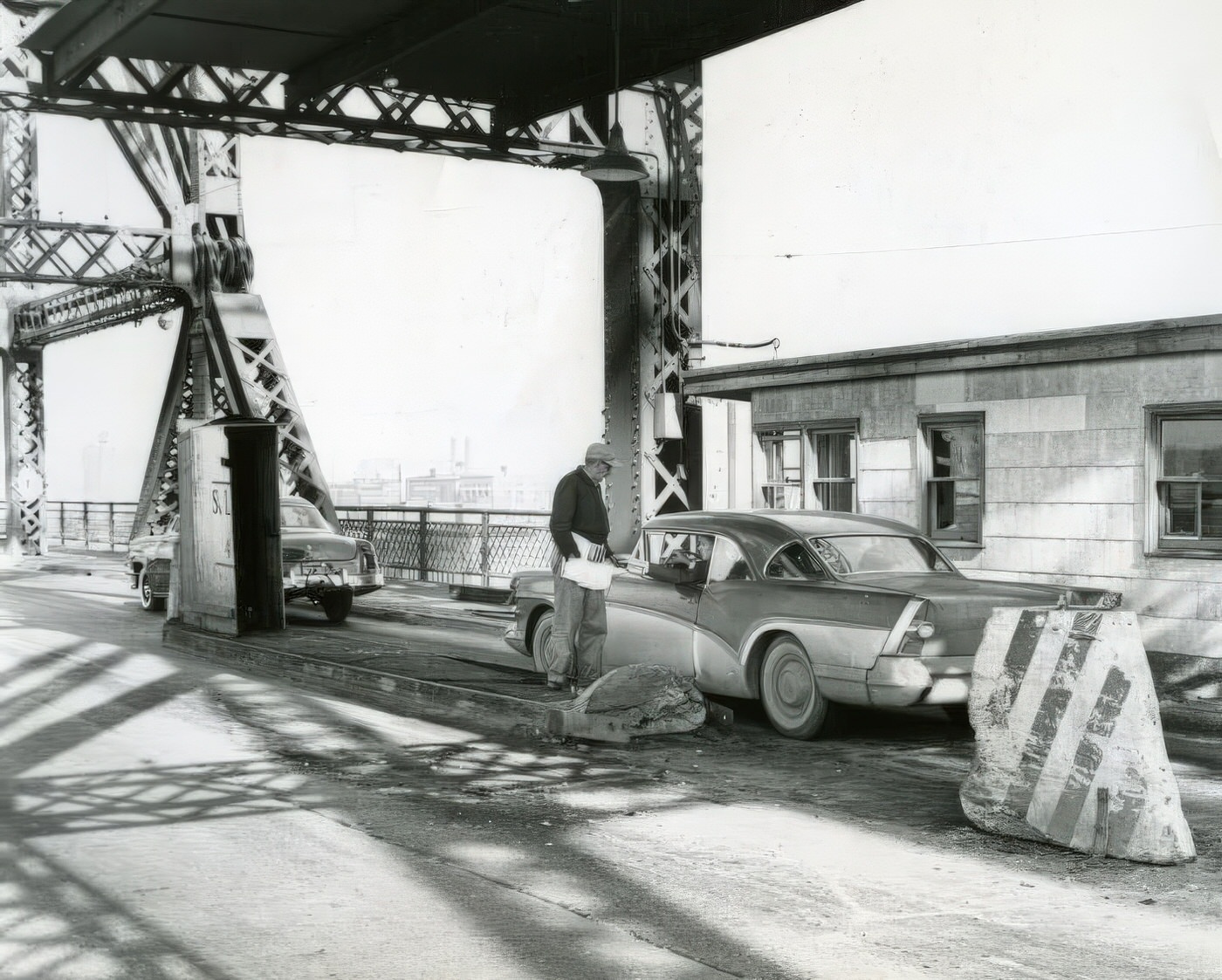

The city’s connection to the wider world was also evolving. The Lambert-St. Louis International Airport terminal, designed by Minoru Yamasaki in the mid-1950s, was already an architectural landmark. In line with its original modular design, an identical fourth concrete vault was added to the existing three in 1965, further expanding its capacity.

These physical changes occurred against a backdrop of profound demographic shifts. The population of the City of St. Louis declined sharply during the decade, falling from 750,026 in 1960 to 622,236 by 1970. This decrease was among the most significant experienced by major U.S. cities at the time. A primary driver of this loss was the “heavy and prolonged out-migration” of the city’s white population, who largely relocated to surrounding suburbs. This exodus of younger white families also left behind an older white population within the city limits. The African American population, while initially maintaining its numbers through natural increase, began to experience a net migratory loss by 1969. Despite this, the proportion of Black residents within the city increased as white out-migration occurred at a faster rate. Consequently, St. Louis saw a growing concentration of what contemporary reports termed “needy or disadvantaged citizens: blacks, the elderly, and families with low incomes”. Problems associated with dependency and poverty became increasingly localized within the city boundaries. This was not merely a movement of people but a fundamental restructuring of the metropolitan area’s social and economic geography, which left the central city with a higher concentration of residents who had fewer resources and choices, directly impacting its capacity to address mounting urban problems. All the while, residential segregation remained a persistent issue, with the majority of Black St. Louisans confined to predominantly Black neighborhoods.

The Fight for Equality: The Civil Rights Movement Roars

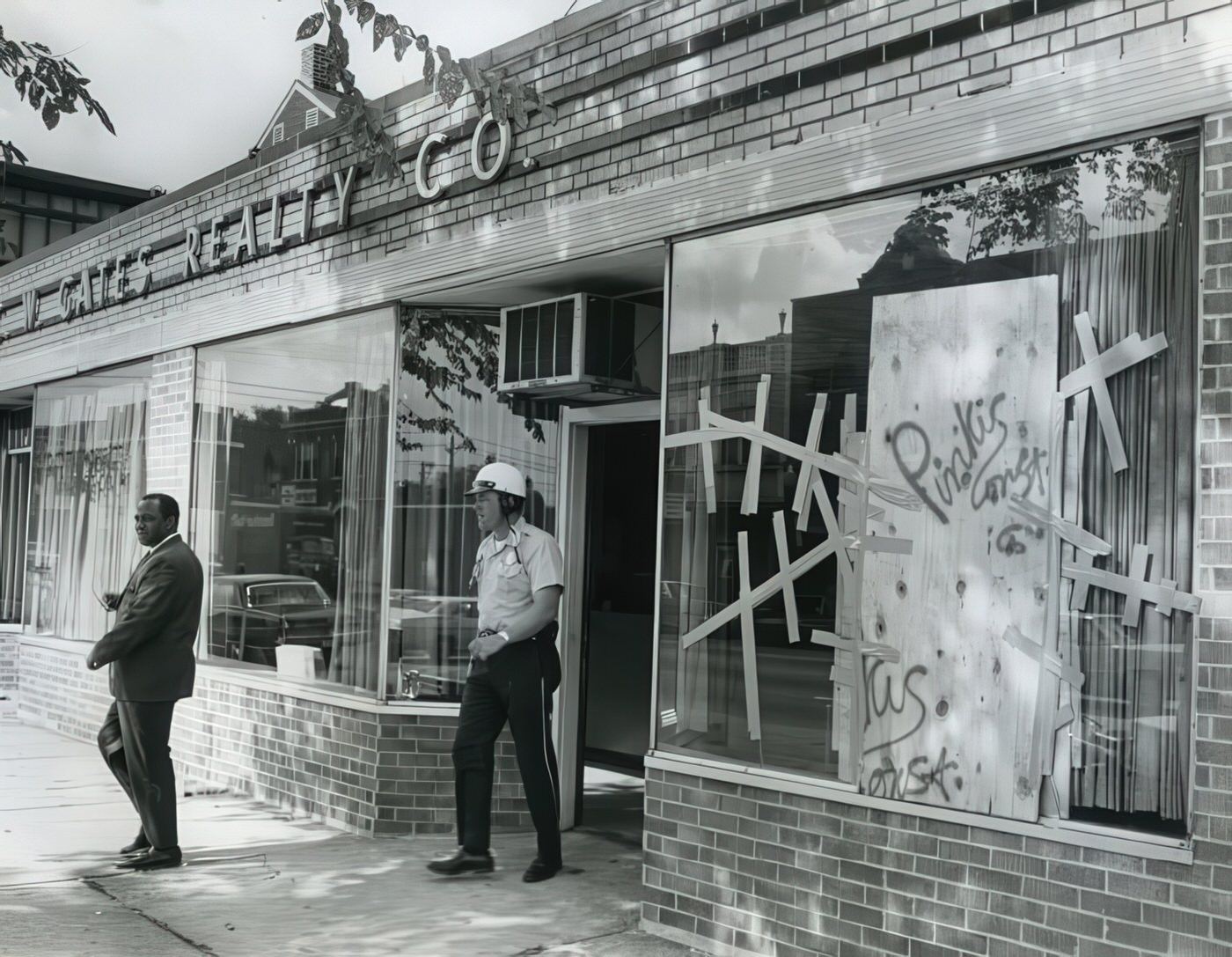

St. Louis in the early 1960s was a city deeply marked by racial segregation. African American Missourians faced systemic discrimination in nearly every facet of life, including schools, housing, employment opportunities, and access to public accommodations such as theaters and recreational facilities. Due to entrenched segregated housing patterns, a majority of Black students attended all-Black schools, even after legal desegregation mandates were in place. In some Missouri communities, the discriminatory practice of “sundown laws,” which prohibited Black people from being in town after dark, still persisted. This pervasive system of segregation formed the critical backdrop against which the Civil Rights Movement in St. Louis gathered force and visibility.

A defining moment in the local struggle was the Jefferson Bank Protests, which began on August 30, 1963. Led by the St. Louis Committee of Racial Equality (CORE), activists launched sustained demonstrations at the Jefferson Bank and Trust Company. Their central demand was for the bank to hire African Americans in clerical and teller positions. This demand was particularly pointed because after the bank relocated from a predominantly Black neighborhood to a white one, its only Black employees were a janitor and a messenger. The bank’s infamous response to the protesters’ demands was that it could not find “four Blacks in the city” qualified for such jobs. Activists, including notable figures like Percy Green and a young city alderman named William L. Clay Sr., faced staunch opposition. The protests led to mass arrests, with over 500 people detained over a four-year period, and many participants received harsh sentences for their non-violent civil disobedience. William L. Clay Sr. himself was jailed for 270 days. Despite court injunctions aimed at stopping them, the demonstrations continued for months, becoming one of the most significant and prolonged confrontations of the civil rights era in St. Louis. The focus on jobs and fair employment practices connected the fight for racial equality directly to the material well-being and opportunities of the Black community. Earlier in 1963, Alderman Clay had released a report titled “Anatomy of an Economic Murder,” which detailed the discriminatory hiring practices of major corporations in the region, laying the groundwork for such economic demands.

The local movement received a significant boost in March 1964 when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited St. Louis. He spoke passionately about the importance of the pending Civil Rights Act and emphasized that its true value would lie in its full and vigorous implementation. Dr. King also warned that more demonstrations would follow if the bill failed to bring about tangible improvements in the lives of African Americans. His visit helped to connect the St. Louis activists with the broader national movement and brought increased attention to their local struggles.

The fight for economic inclusion took a dramatic turn on July 14, 1964, just twelve days after the landmark Civil Rights Act was signed into law. CORE activists Percy Green and Richard Daly scaled a 125-foot construction ladder on the side of the still-unfinished Gateway Arch. Their audacious protest aimed to demand more jobs for Black workers on the federally funded construction project. After safely descending, both men were arrested. This bold action at a highly visible national symbol underscored the continued fight for economic justice even after significant legislative victories.

The City’s Shifting Economic Engine: Industry, Employment, and Change

The 1960s marked a period of significant transition for St. Louis’s economy, with some sectors soaring while others faced decline. The aerospace industry emerged as a major bright spot, largely driven by the Cold War and the burgeoning Space Race. McDonnell Douglas Corporation was at the forefront of this activity in St. Louis. The company secured crucial contracts from NASA to build the Mercury spacecraft, which carried astronaut John Glenn on his historic orbit in 1962, and the Gemini spacecraft, which played a vital role in developing techniques necessary for the Apollo moon missions. McDonnell Douglas was a substantial employer in the region, and its merger with Douglas Aircraft Company in 1967 further solidified its prominent position in the aerospace field and its economic importance to St. Louis. This boom in aerospace, fueled by government investment and technological advancement, contrasted sharply with the fortunes of the city’s more traditional manufacturing base.

While national manufacturing employment saw growth during the 1960s , St. Louis, which had historically overspecialized in heavy industries such as automotive manufacturing, trucks, and primary metals, encountered significant challenges. Over a broader period that encompassed the 1960s, the city experienced a substantial loss of 92,000 manufacturing jobs. The General Motors plant in St. Louis was a key component of the local automotive sector. National economic reports from as early as July 1960 indicated job cutbacks in the steel and auto industries, signaling the pressures these sectors were facing. The garment industry, historically centered on Washington Avenue, still provided employment for around 12,000 people in 1967, but it too was part of a manufacturing landscape undergoing transformation. St. Louis was, in effect, experiencing the early phases of the “Rust Belt” phenomenon, where established industrial cities faced decline as manufacturing patterns shifted nationally and globally.

The economic hardship was particularly acute across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis, Illinois. Once a thriving industrial town, East St. Louis was described as being on the “precipice of disaster” by the early 1960s. Between 1960 and 1970, the city lost nearly 70 percent of its businesses, and unemployment rates soared. An ineffective city government struggled to cope, leading to a rapidly shrinking tax base and severe cuts in essential city services. The severe economic collapse of East St. Louis served as a stark illustration of regional distress and likely exacerbated challenges in St. Louis, Missouri, through migration patterns and by contributing to a wider perception of economic decline in the metropolitan area.

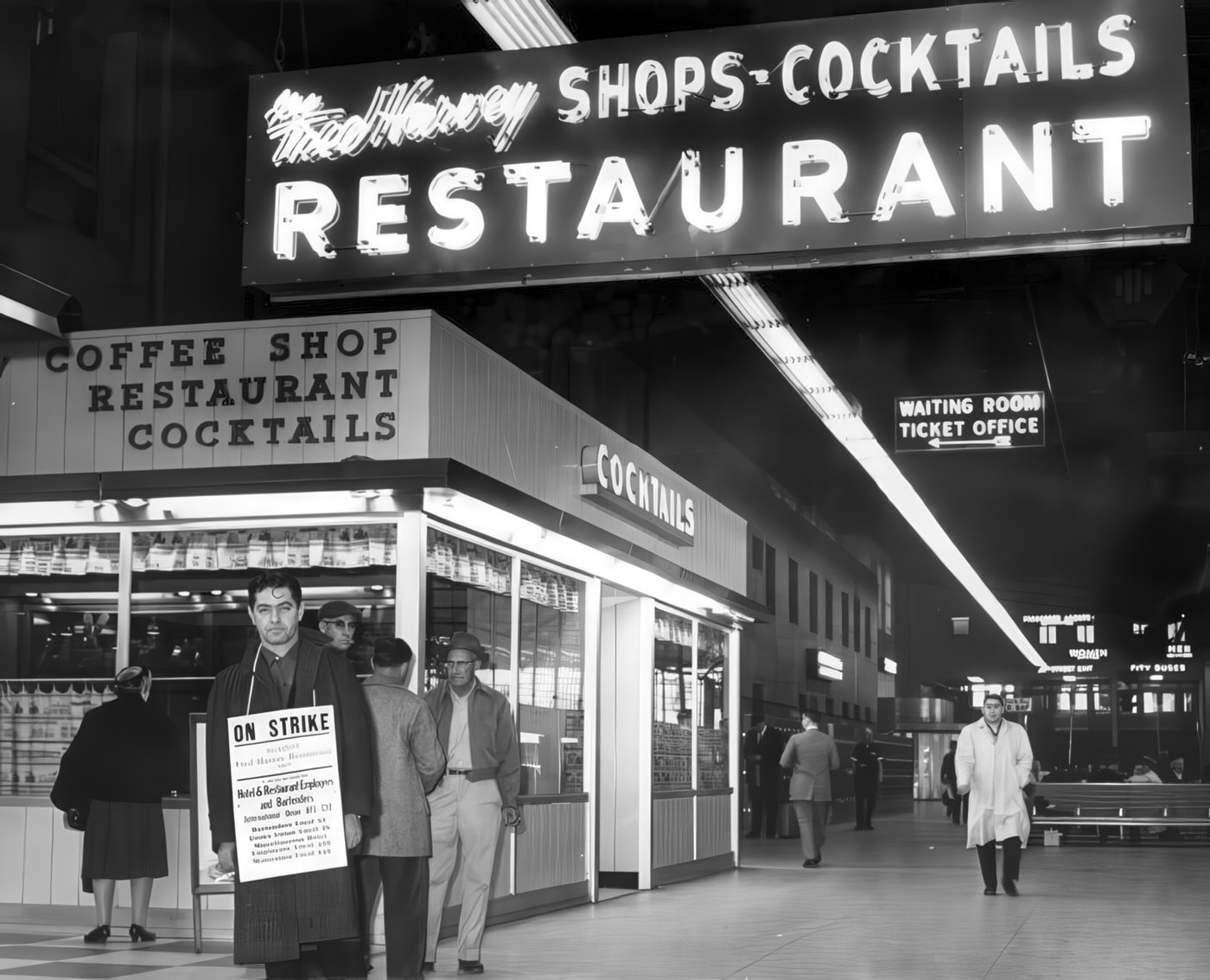

Labor and employment trends during the decade also reflected the changing economic climate. Nationally, the year 1960 saw a relatively low level of strike activity, although the average duration of strikes that did occur was notably high. Manufacturing industries continued to experience more strikes than non-manufacturing sectors. A significant labor action later in the decade was the 1968 Communications Workers of America (CWA) strike against the Bell System. This was the first national telephone strike since 1947 and involved approximately 200,000 workers who sought wage increases to keep pace with the rising cost of living. The strike caused considerable disruption in telephone services in major cities and contributed to a high number of workdays lost due to stoppages in 1968. Such labor actions, occurring amidst deindustrialization and economic uncertainty, highlighted a period of heightened worker anxiety and a growing assertiveness regarding their economic standing, even in sectors not directly facing mass layoffs.

Daily Rhythms and Cultural Beats: Life in 1960s St. Louis

Amidst the social and economic transformations, the daily life and cultural heartbeat of St. Louis continued with vibrancy and change. The city’s music scene was particularly dynamic, serving as a significant hub for blues, jazz, and the evolving sounds of rock and roll. East St. Louis, Illinois, also boasted a lively and closely interconnected music scene that contributed to the region’s rich musical tapestry.

Several St. Louis artists achieved national and international recognition. Chuck Berry, a true pioneer of rock and roll, was a native St. Louisan who frequently performed in local venues. The powerful duo Ike & Tina Turner, known for their energetic R&B and rock and roll performances, had strong ties to both St. Louis and East St. Louis. Oliver Sain emerged as a central figure in the St. Louis soul scene. A talented bandleader, musician, and producer, Sain opened Archway Studios in 1965, which became a recording home for many prominent artists, including Fontella Bass, Bobby McClure, Albert King, and Little Milton. Fontella Bass herself, celebrated for her powerful soul vocals, was highly active during the 1960s. The city’s jazz heritage continued with artists like Grant Green, Clark Terry, and Charles Kynard, who had St. Louis connections and were active during this era. The richness of this music scene, particularly in genres like blues, jazz, and soul that were deeply rooted in African American culture, provided a vibrant cultural expression that coexisted with, and perhaps offered a counterpoint to, the racial segregation and social tensions prevalent in the city. Music venues often became important spaces for community expression and, in some instances, for interactions that were less common in other public spheres.

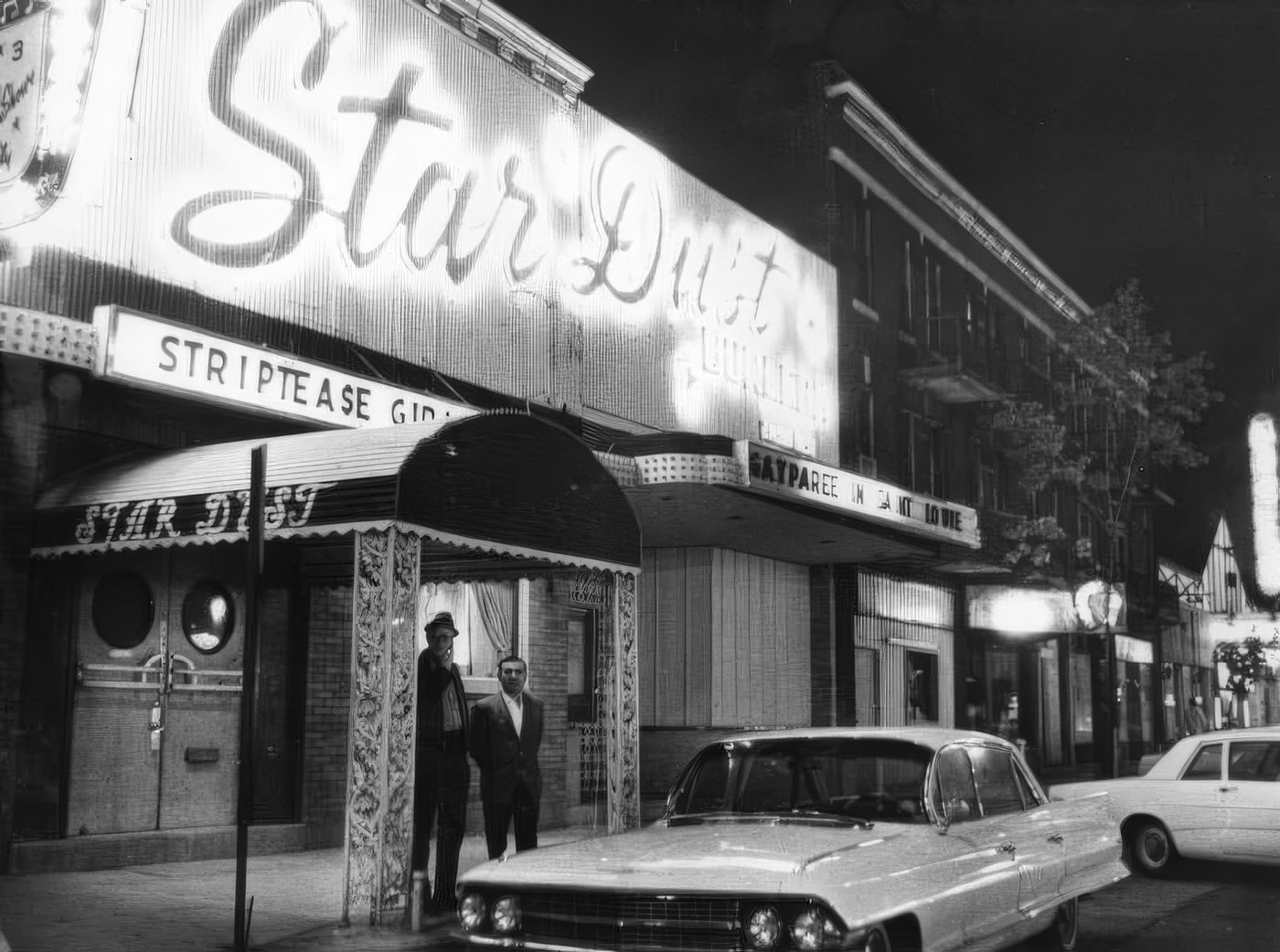

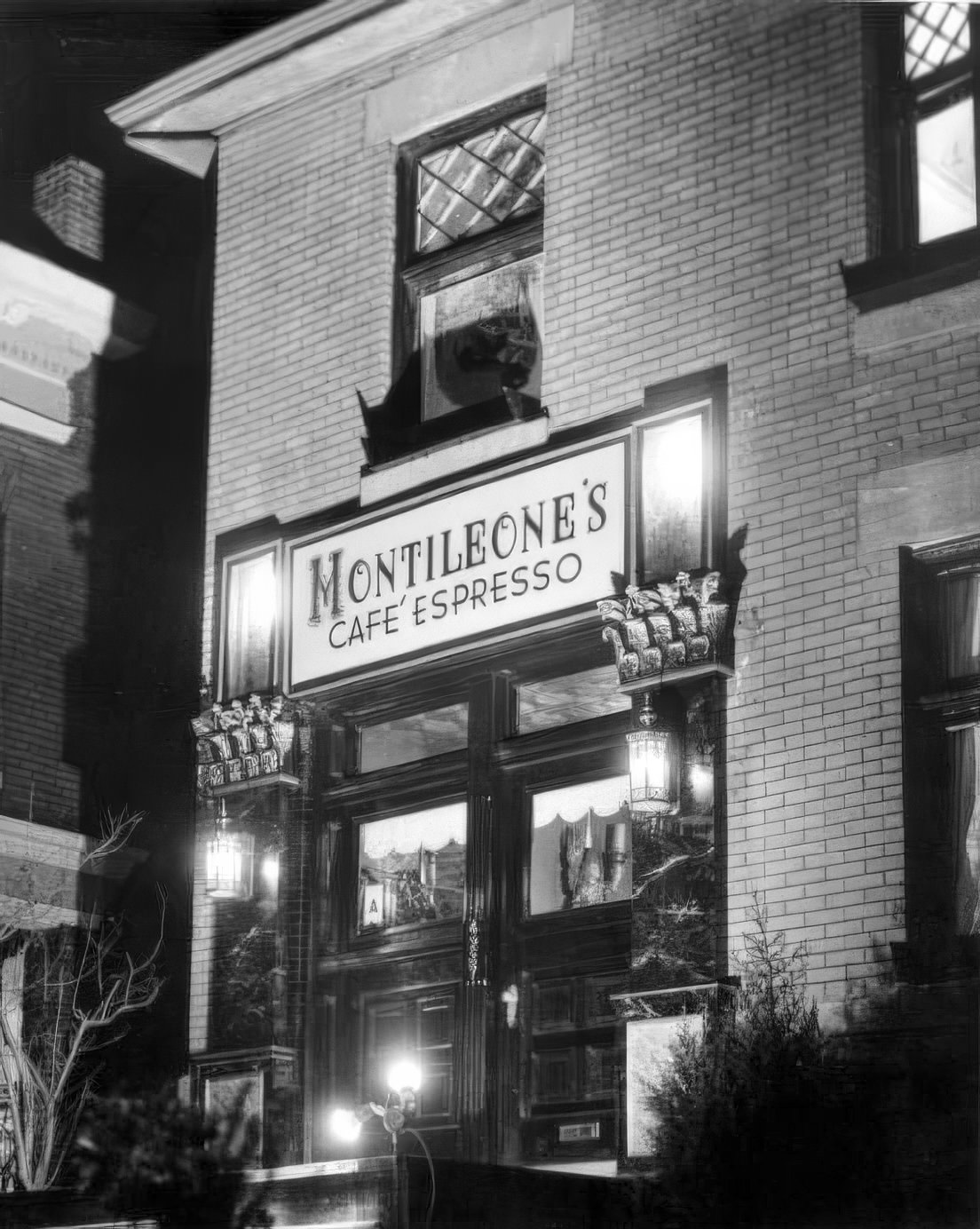

Popular entertainment venues dotted the city. Gaslight Square was a nationally recognized entertainment district, especially renowned for jazz music, throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, with clubs like Peacock Alley hosting notable performances. Across the river, the Blue Note Club and the Cosmopolitan in East St. Louis attracted major talent and large local crowds. While its prominence grew significantly in later decades, Blueberry Hill’s Duck Room in the Delmar Loop was also beginning to establish itself as a music venue.

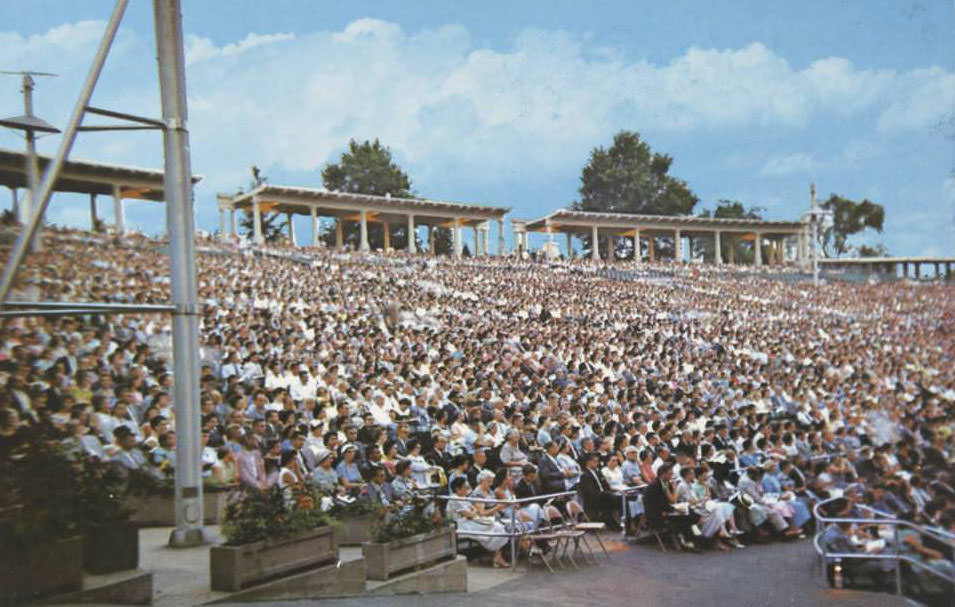

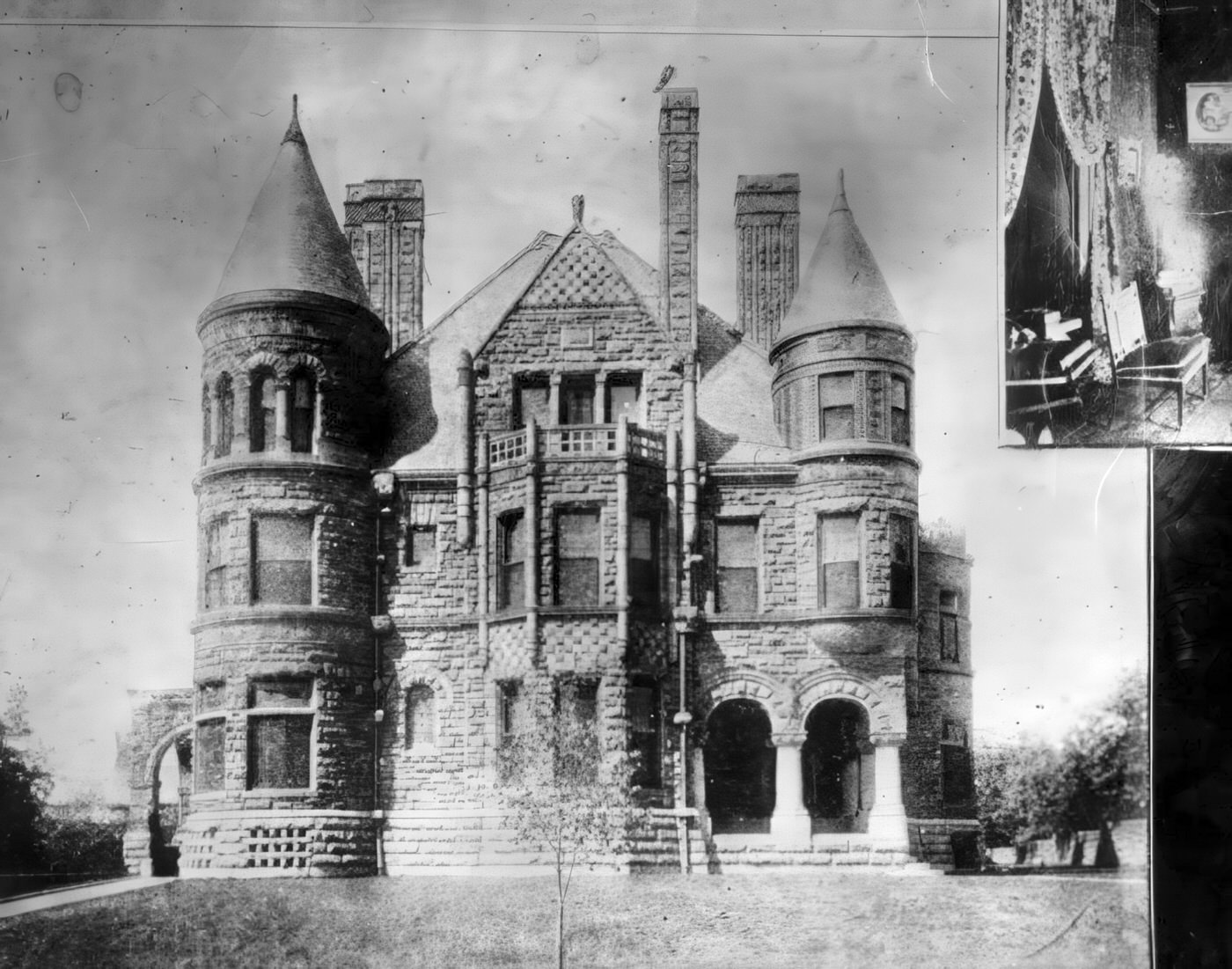

Leisure activities and social life in St. Louis offered a variety of options. Forest Park remained a central gathering place, home to esteemed institutions like the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Saint Louis Zoo, and The Muny, an iconic outdoor musical theatre. The historic Fox Theatre, located in the Grand Center arts district, presented Broadway shows and other major performance events. For more casual entertainment, drive-in theaters such as the Holiday, Airway Twin, I-44, South Twin, North Twin, and Ronnies were popular hangouts for teenagers and families, offering double features under the stars. The Laclede’s Landing area, with its deep historical roots as the city’s original riverfront, was beginning to see renewed interest in historic preservation during the 1960s, laying the groundwork for its later development into a dining and entertainment district. This diversity of leisure, from high culture to mass entertainment, indicated a society with varied tastes where shared cultural experiences could still occur, even as the city was undergoing significant demographic fragmentation.

Fashion trends in St. Louis mirrored those seen across the nation. The early 1960s saw more conservative styles, but as the decade progressed, fashion became more expressive, with the rise of miniskirts, A-line dresses, and eventually bell-bottom pants and hippie-influenced attire. The “space-age” look, characterized by the use of synthetic materials and bold geometric shapes, also made an appearance. Men’s fashion similarly evolved from more traditional suits to include brighter colors, more casual styles, and longer hair. St. Louis’s own garment district on Washington Avenue was a significant source of junior wear and other clothing, contributing to these evolving styles. These visible changes in dress on the streets of St. Louis reflected broader societal shifts in youth culture, evolving gender roles, and a growing emphasis on individuality, occurring even as the city grappled with profound economic and social challenges.

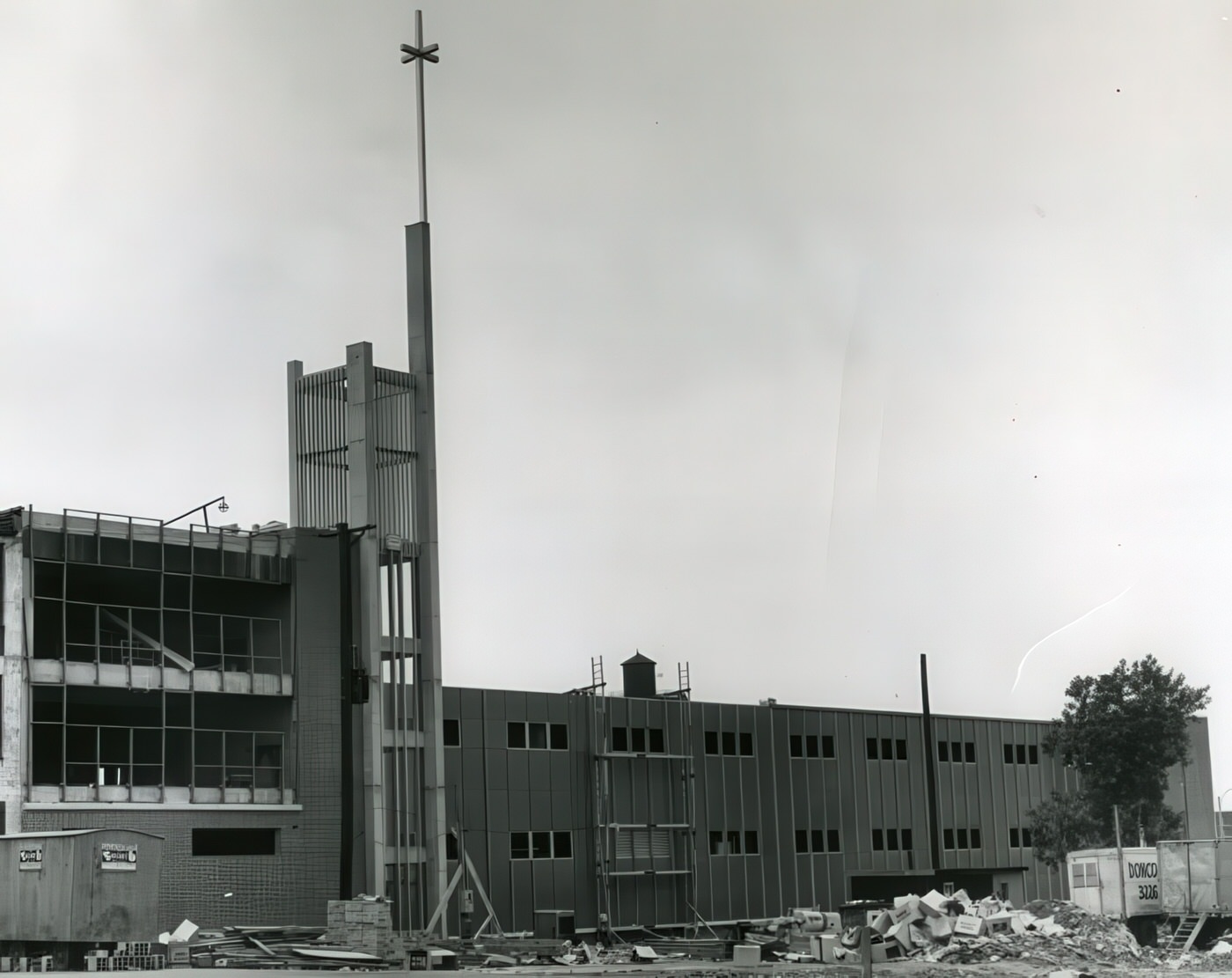

The city’s cultural and civic life was also marked by the presence of important institutions. The Saint Louis Abbey Church, with its distinctive and award-winning architecture, was completed in 1962, adding a modern spiritual landmark to the cityscape. Organizations like the Agribusiness Club of St. Louis, formerly known as the Farmers’ Club, continued to be active in promoting specific sectors of the regional economy.

City Hall, Civic Action, and Stirrings of New Movements

The political and civic landscape of St. Louis in the 1960s was as dynamic and contested as its social and economic spheres. Alfonso J. Cervantes began his tenure as mayor in April 1965, having defeated the incumbent Raymond Tucker. His administration confronted a city in flux, focusing on traditional urban concerns such as crime-fighting, for which he established a Commission on Crime and Law Enforcement and implemented new regulations for pawnshops. He also secured funding for mounted police through a sales tax. Cervantes addressed city finances through bond issues aimed at completing the Arch grounds, improving street lighting, and constructing a juvenile center. Furthermore, he sought to stimulate economic activity by creating a Business Development Commission and a Land Reutilization Authority to manage vacant properties. However, Mayor Cervantes governed during a period increasingly shaped by powerful social movements and deep-seated structural problems like segregation, economic decline, and a severe housing crisis, necessitating a constant effort to balance maintaining order, promoting growth, and responding to escalating citizen demands for change.

One of the most potent examples of grassroots activism was the 1969 Pruitt-Igoe Rent Strike. Beginning in February of that year, tenants in St. Louis public housing, prominently including residents of the notorious Pruitt-Igoe complex, initiated a nine-month rent strike. They protested intolerable living conditions, alleged mismanagement of funds by the housing authority, and proposed rent increases that would have consumed a disproportionate share of their meager incomes. Bertha Gilkey, a resident of Pruitt-Igoe, emerged as a key and articulate leader of this movement. The strike garnered national attention, highlighting the crisis in public housing. A crucial factor in its resolution was the intervention and support of Teamsters Union leader Harold Gibbons and Local 688, who provided financial assistance, meeting spaces, and negotiating expertise. The strike concluded not only with a rollback of rents but, more significantly, with the formation of the St. Louis Civic Alliance for Housing. This innovative partnership included tenants, who were granted one-third of the seats on its board, alongside representatives from business, labor, and community leadership, to collectively administer public housing in the city. The success of this strike demonstrated a notable shift in power dynamics, where marginalized communities, through determined activism and strategic alliances, could compel significant concessions from city authorities and even influence federal housing policy engagement, as evidenced by HUD’s involvement in the settlement.

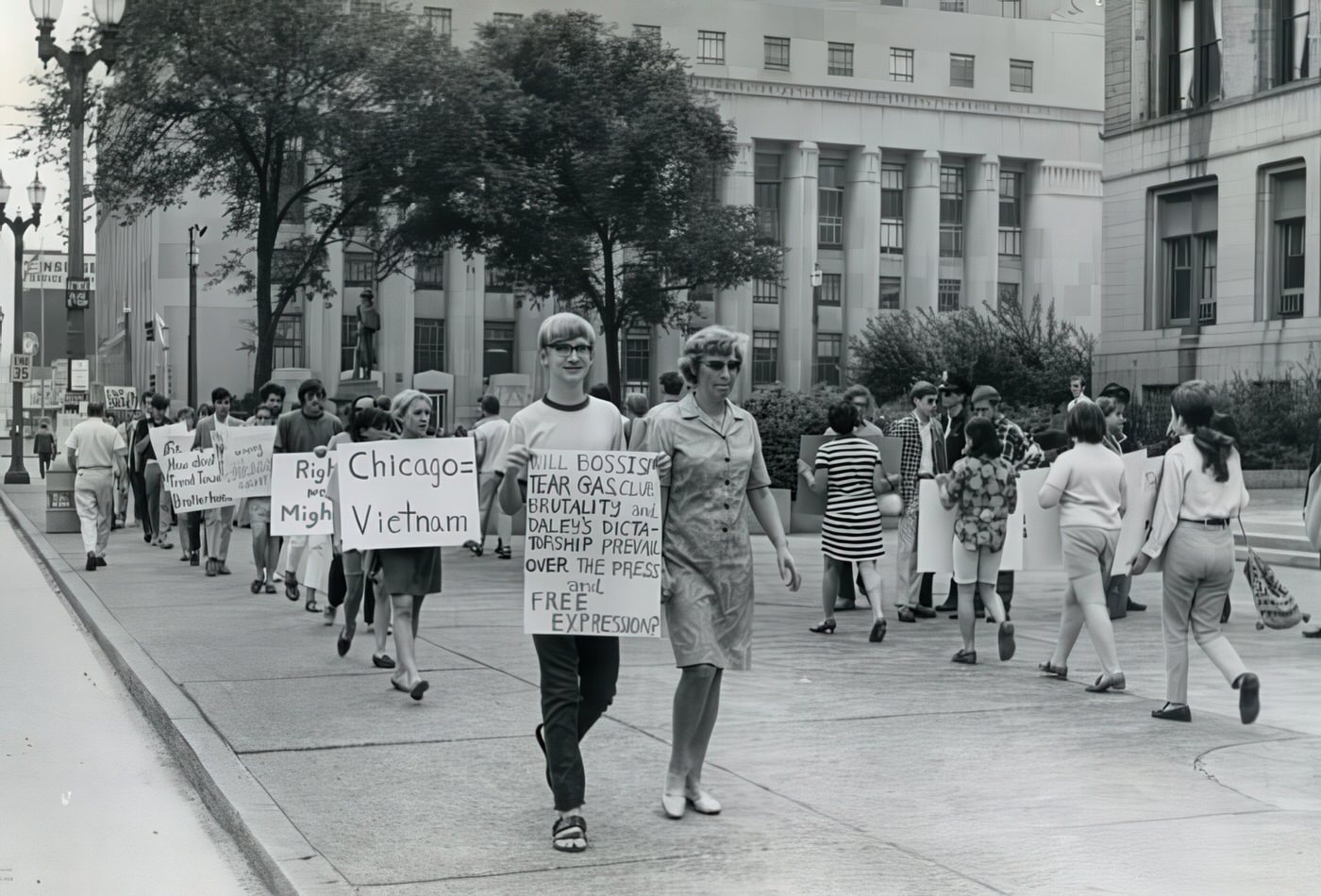

Beyond the Civil Rights Movement and tenant organizing, St. Louis witnessed the emergence of other grassroots movements, reflecting broader national currents. Environmental activism gained local traction with initiatives like the St. Louis Baby Tooth Survey. In this citizen-led effort, local women organized the collection of thousands of baby teeth to measure levels of radioactive strontium-90, a byproduct of atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, raising public awareness about environmental health hazards. The feminist movement was also taking root in St. Louis during the 1960s and into the 1970s, with local women organizing around issues of equality, reproductive rights, and broader social transformation, mirroring the growing momentum of the women’s liberation movement nationwide. As the Vietnam War escalated, anti-war sentiment grew, leading to student activism and protests in St. Louis, similar to those occurring on campuses and in cities across America. These protests often targeted the draft, government war policies, and companies involved in war production. The late 1960s also saw early organizing within the St. Louis LGBTQ+ community. The founding of the Mandrake Society in 1969 provided an initial organizational focus. A particularly notable local event occurred on Halloween night in 1969 when nine men in drag were arrested for violating an old city ordinance against “masquerading.” The community, with the support of the Mandrake Society, quickly rallied to bail them out, and the charges were later dismissed. This incident is viewed by some as a “St. Louis Stonewall,” a significant moment of resistance and community solidarity. The rise of these diverse movements indicated a broadening of social consciousness, reflecting national trends but also taking on local characteristics as activists addressed issues specific to St. Louis.

Underlying many of the city’s challenges were persistent issues of governance and the deep division between St. Louis City and St. Louis County. Regional planners in the early 1960s described this separation as a “Berlin Wall” that severely hampered efforts to address metropolitan-wide problems like segregation, transportation, and urban decline. The principle of “home rule,” which granted autonomy to the numerous municipalities within St. Louis County, often resulted in fragmented planning and exclusionary zoning practices that exacerbated racial and economic disparities. An ambitious proposal in 1962 to create a more unified regional governance structure, known as the Borough Plan, ultimately failed to gain approval. In an attempt to manage accelerating suburban growth, the St. Louis County Council adopted a new comprehensive Zoning Ordinance in 1965, which included the creation of a Non-Urban District category.

Image Credits: The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Library of Congress, St. Louis Public Library,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know