On a spring afternoon in 1896, the bustling city of St. Louis, Missouri, and its neighbor across the river, East St. Louis, Illinois, were forever marked by a catastrophic weather event. What began as an ordinary day transformed into a scene of unimaginable destruction as a powerful tornado, later dubbed the “Great Cyclone,” tore through the heart of the metropolitan area. The storm’s fury left a wide scar of ruin, claiming hundreds of lives and altering the landscape of a city then considered the nation’s fourth largest.

The Calm Before the Storm: A City Unaware

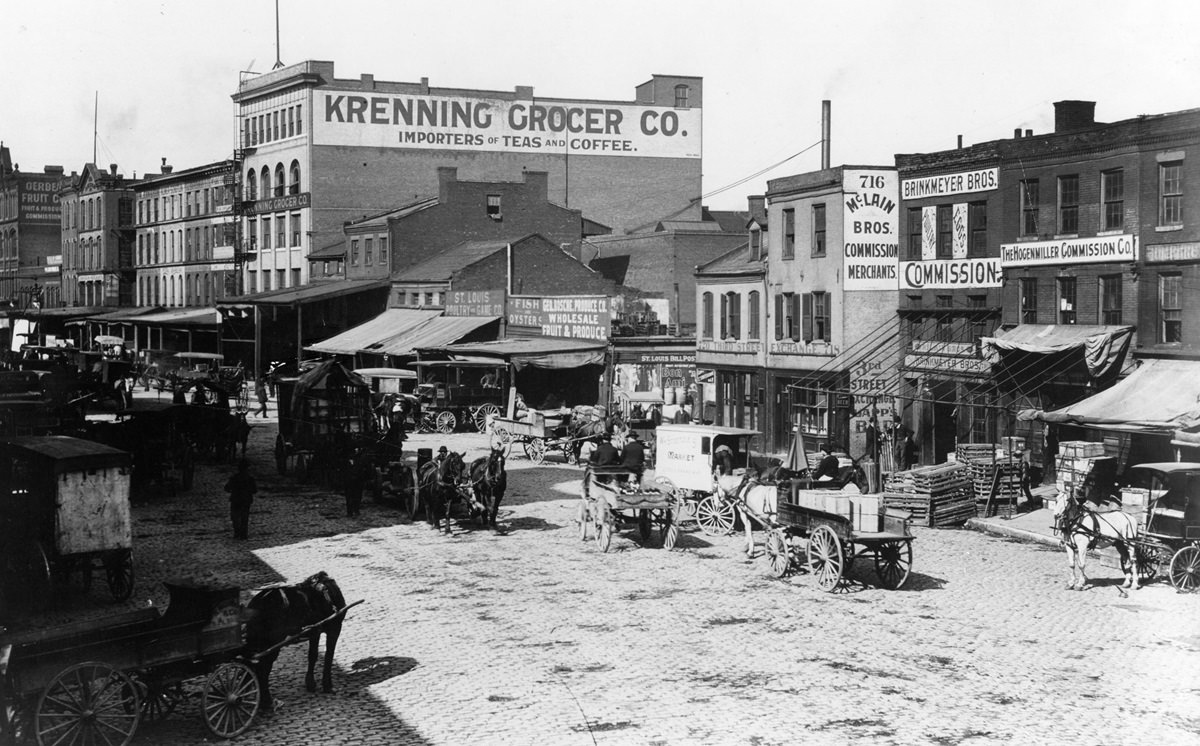

Wednesday, May 27, 1896, dawned warm and muggy in St. Louis, typical for late spring in the Midwest. The city, a major hub of commerce and transportation, was alive with activity. Its citizens went about their daily routines, unaware of the atmospheric battle brewing above them. The Weather Bureau Observatory, with the limited forecasting technology of the era, was not overly concerned, though some residents felt an uneasy sense of anticipation as the day progressed.

The Fury Unleashed: Meteorology and Timeline of the Great Cyclone

The tornado that struck St. Louis was the violent culmination of an extended period of unusual weather. For forty-nine consecutive days, from April 9 to May 27, the mean temperature in St. Louis had been consistently above normal, ranging from 2 to 21 degrees higher than average. The days leading up to the tornado saw this heat intensified by unusually high humidity.

On the morning of May 27, the weather map indicated a low-pressure system centered over Kansas and Nebraska, placing Missouri in its volatile southeast quadrant. St. Louis experienced clear weather with southerly winds of 8 miles per hour and a very high relative humidity of 94 percent at 8:00 a.m.. By noon, the barometer had fallen slightly, and the temperature had risen to 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The wind shifted to the southwest, and a veil of alto-stratus clouds hung over the city.

The atmospheric conditions grew more ominous as the afternoon wore on. After 3:00 p.m., the sky began to darken, and both the barometer and thermometer started to fall. By 3:35 p.m., the sun was obscured, and the clouds transformed into a peculiar formation of small, dark gray cumuli with rounded portions underneath. By 4:30 p.m., these clouds had settled into a uniform stratus layer, which began to take on a light green color in the northwest, a sight that often precedes severe weather. Thunder and lightning commenced at 5:06 p.m., followed by large, scattered raindrops at 5:43 p.m..

Just after 5:00 p.m., the barometric pressure dropped sharply. The clouds swirled ominously, adopting a menacing greenish hue. At approximately 5:15 p.m., the tornado touched down about 6 miles west of the Eads Bridge, at the southwest edge of St. Louis. It rapidly intensified and widened, becoming a destructive complex of tornado and downburst winds, carving a path due east toward the central city. The main vortex was part of a larger system, as another F2 tornado had struck near Bellflower, Missouri, earlier that afternoon, and an F3 tornado hit Audrain County around 6:15 p.m., causing fatalities at two schools. The St. Louis tornado itself would later be classified as an F4 on the Fujita scale, with estimated wind speeds between 168 and 199 mph. The storm system unleashed its worst fury on St. Louis and East St. Louis in about twenty minutes. Drenching rains and lightning continued to plague St. Louis until about 9:00 p.m..

A Path of Utter Destruction: St. Louis and East St. Louis Devastated

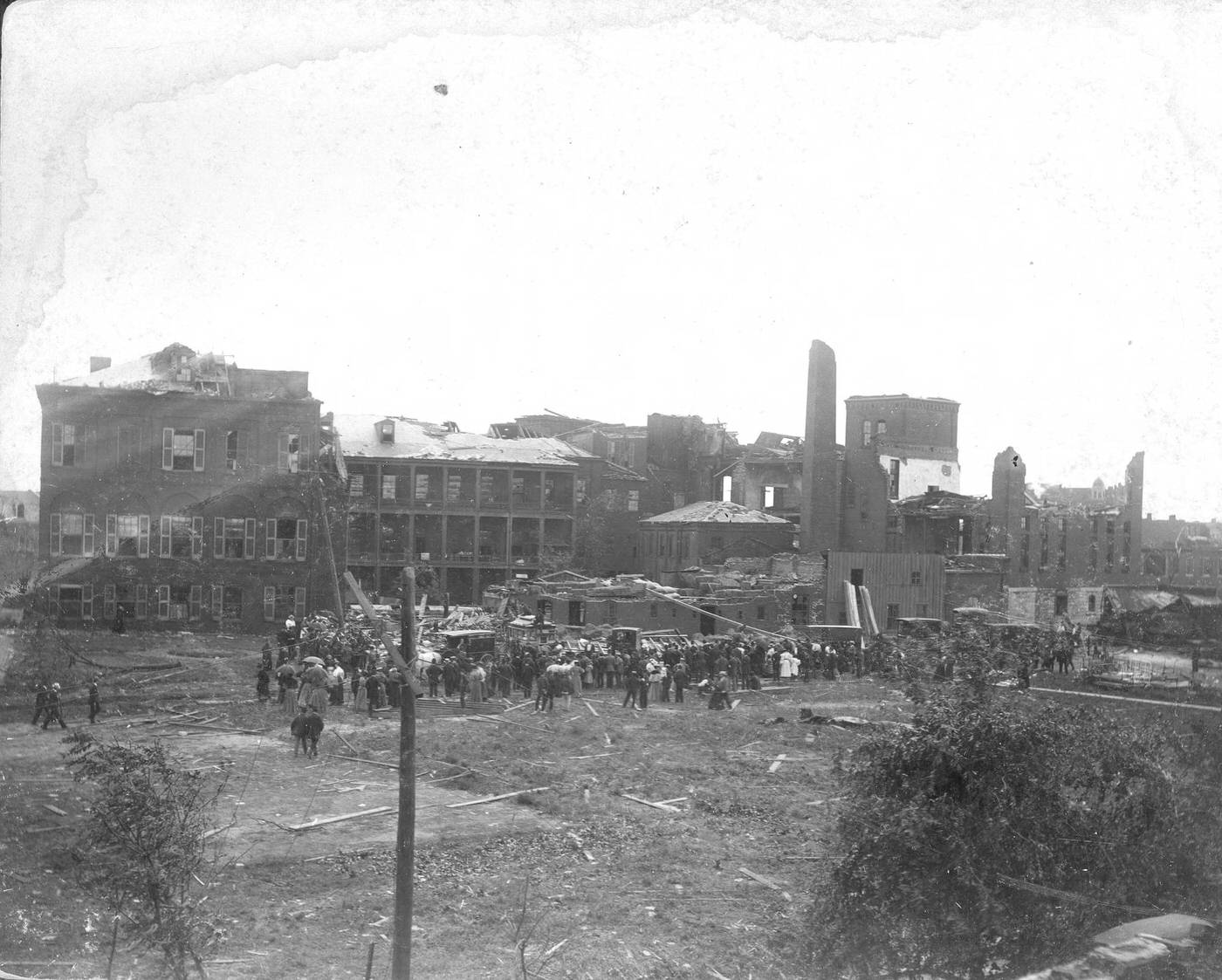

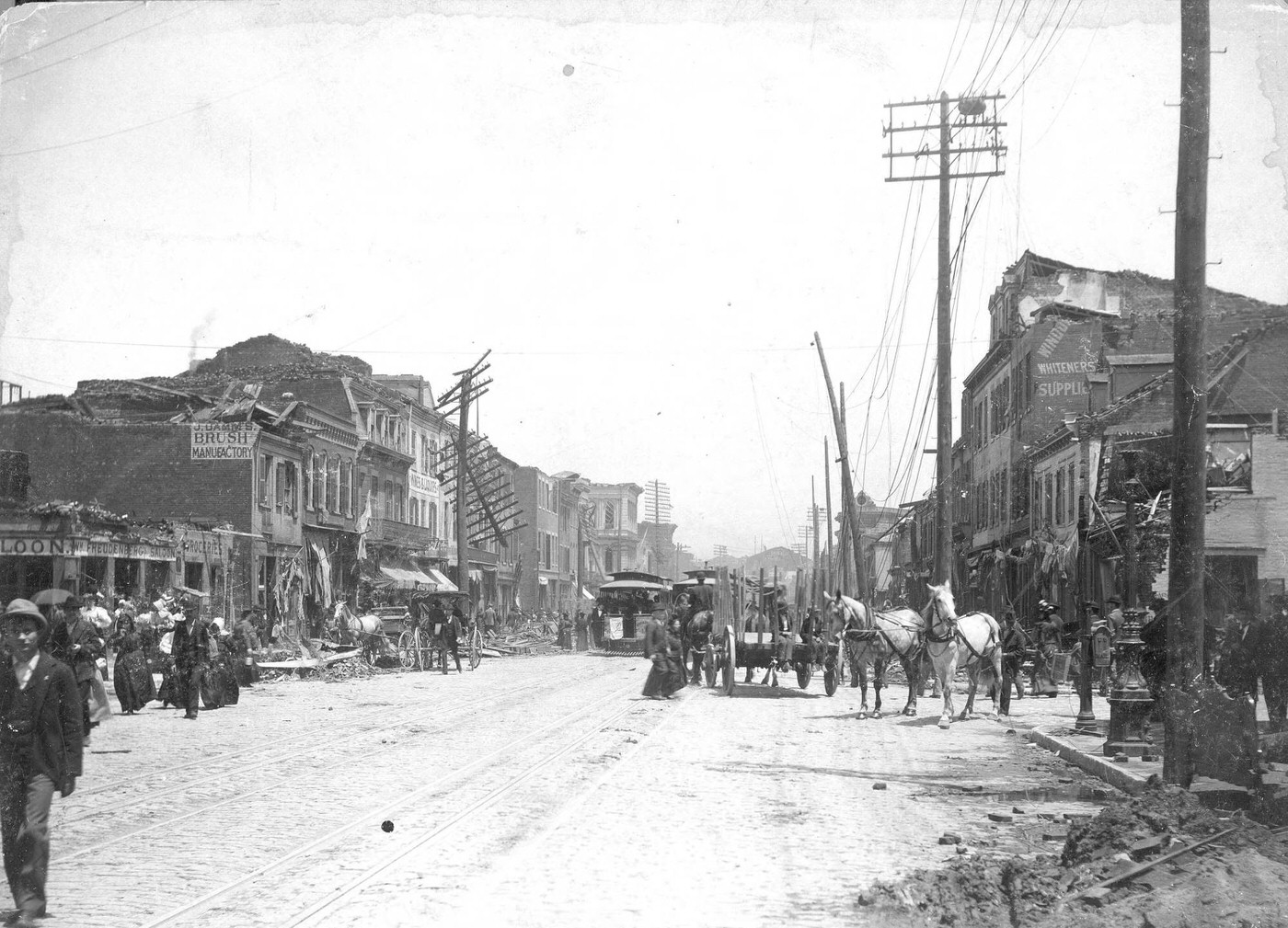

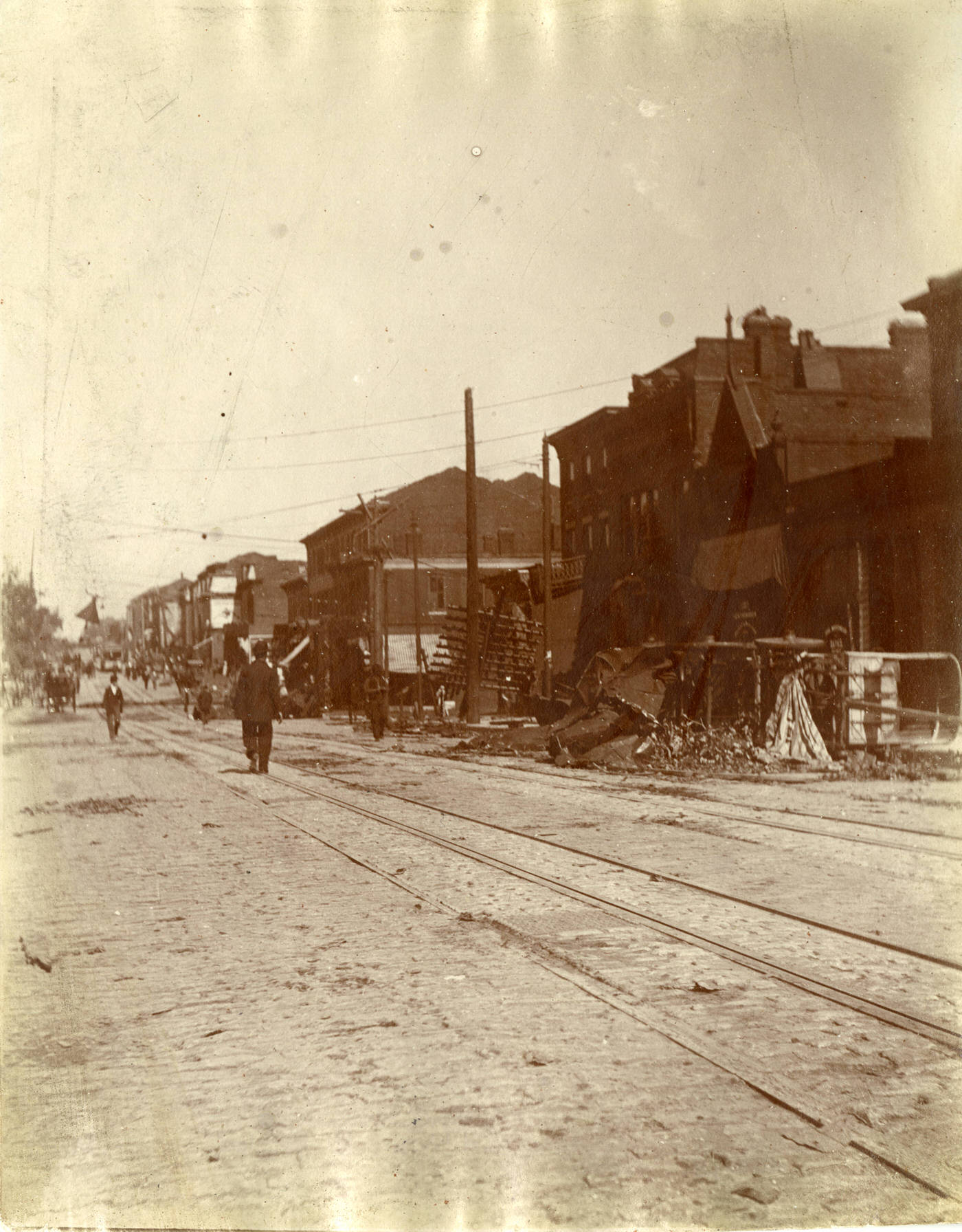

The Great Cyclone carved a brutal path approximately 10 miles long and, in some places, a mile wide through St. Louis. Its journey began in the southwestern part of the city, moving eastward towards the Mississippi River. Entire neighborhoods were left in shambles. The fashionable Lafayette Square and Compton Heights neighborhoods, known for their stone and brick houses, were heavily damaged, as was the poorer Mill Creek Valley. The flimsy wooden houses in less affluent areas offered little resistance to the tornado’s power.

Lafayette Park, a beloved city oasis, was turned into “a wasteland of stripped trees and stumps”. Scarcely a tree was left standing, and the park’s ornate bandstand dome was ripped off and thrown to the ground. The iron fence surrounding the park was flattened in many places. Other specific locations that suffered immense damage included the Soulard area and its market, which was destroyed.

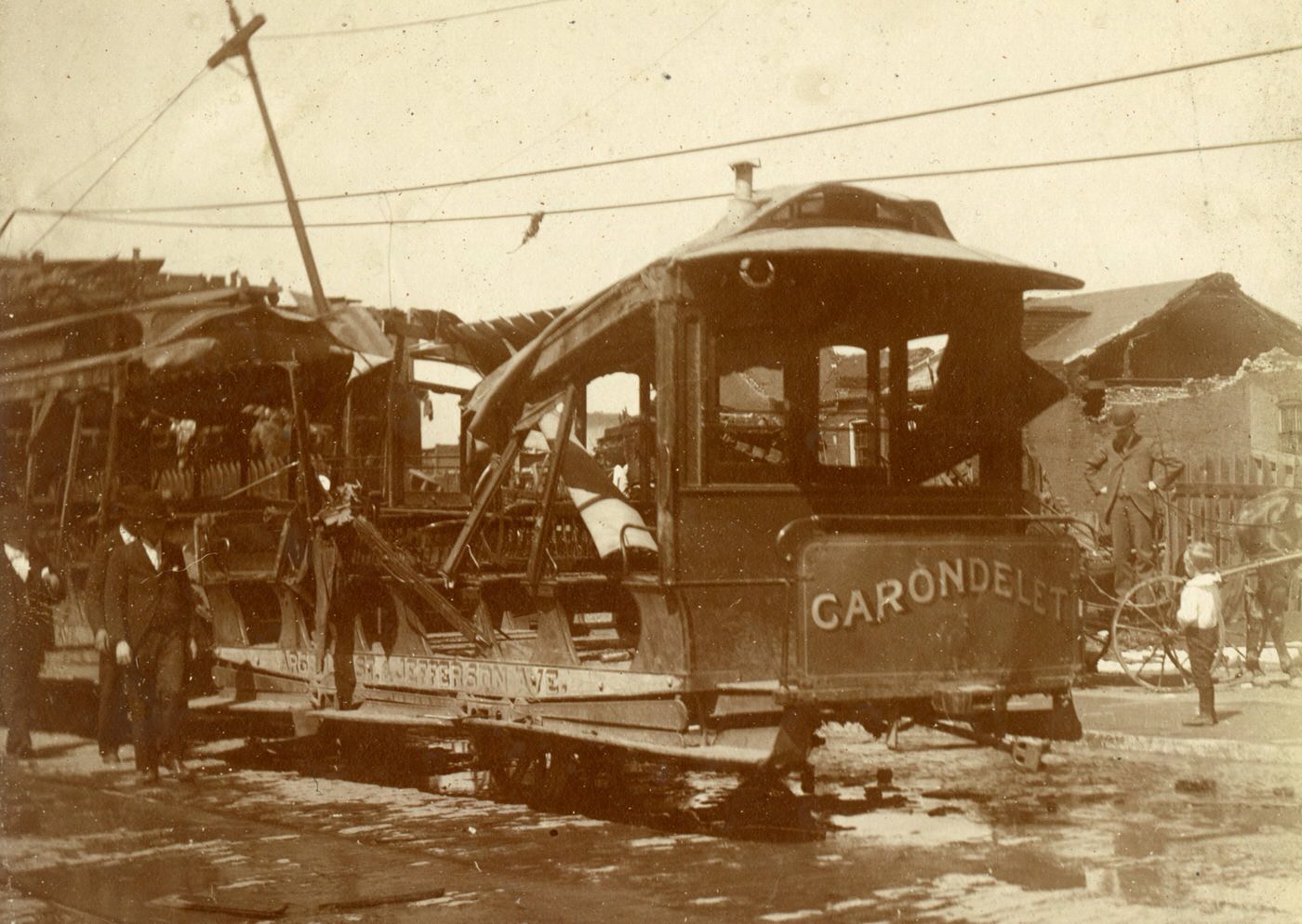

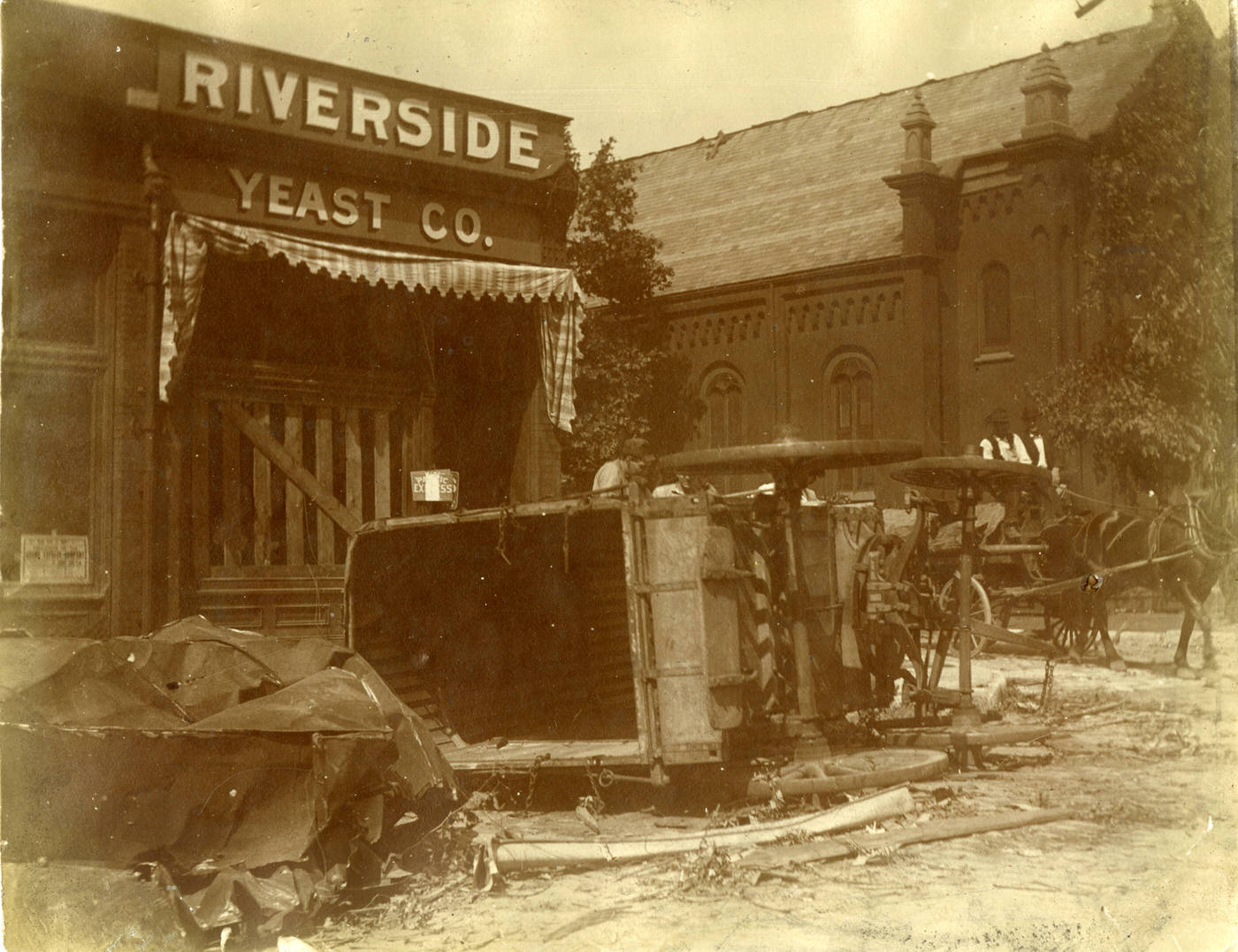

The human infrastructure of the city suffered grievously. Six churches were demolished, and fifteen others were damaged. Among those destroyed were the Mount Cavalry Protestant Episcopal Church at Lafayette and Jefferson Avenue and St. Paul’s German Evangelical Church at 9th Street and Lafayette Avenue. Several city hospitals, including the City Hospital, sustained varying degrees of destruction. Businesses were not spared; the Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company complex, then under construction, saw its structures collapse. The People’s Railroad Power House on Park Avenue and the Riverside Yeast Company on Chouteau Avenue were also damaged. Residential areas bore the brunt of the storm, with countless homes, from grand mansions to modest tenements, reduced to rubble. A three-story brick tenement at Seventh and Rutgers Street collapsed, claiming 17 lives.

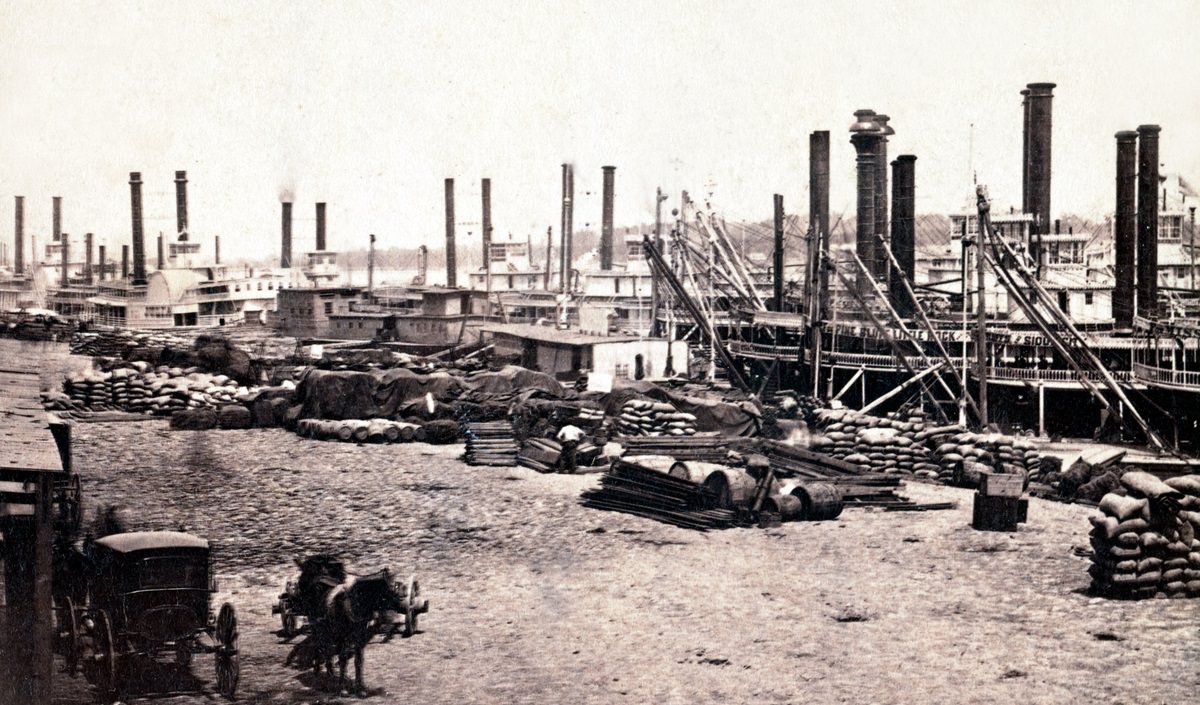

As the tornado reached the Mississippi River, it appeared to gain its maximum intensity. Fortunately, a slight turn in its path spared the tall buildings of downtown St. Louis from a direct hit. However, the riverfront itself became a scene of chaos. Sixteen boats moored in St. Louis harbor were wrecked. The Eads Bridge, an engineering marvel of its time and proclaimed “tornado-proof,” endured the storm’s passage but did not escape unscathed. While the main steel structure of the bridge held, nearly 300 feet of its eastern approach in East St. Louis was torn away. The force of the wind was so great that a 2-by-10-inch wooden plank was driven through a 5/16-inch thick wrought-iron plate on the bridge.

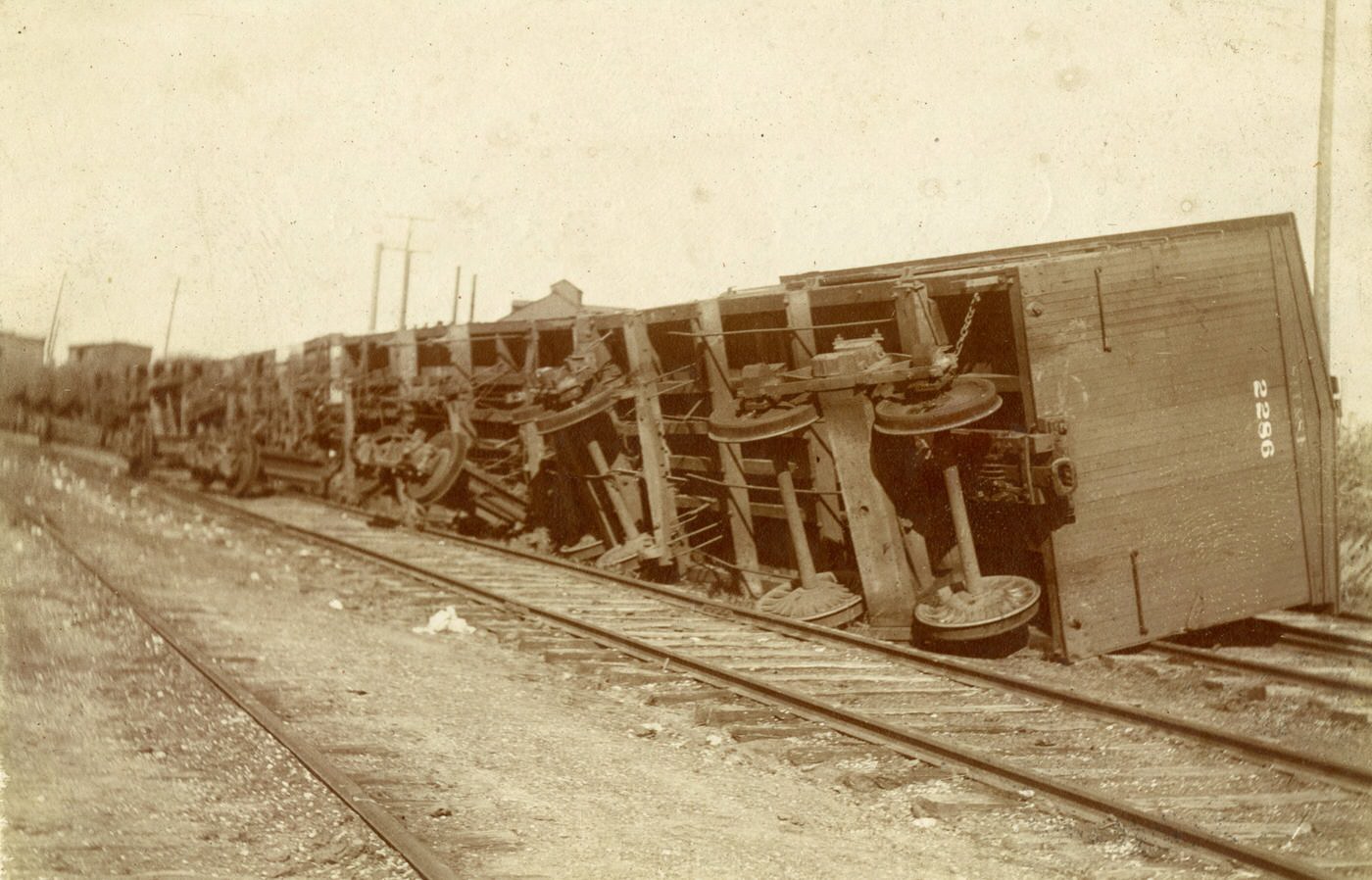

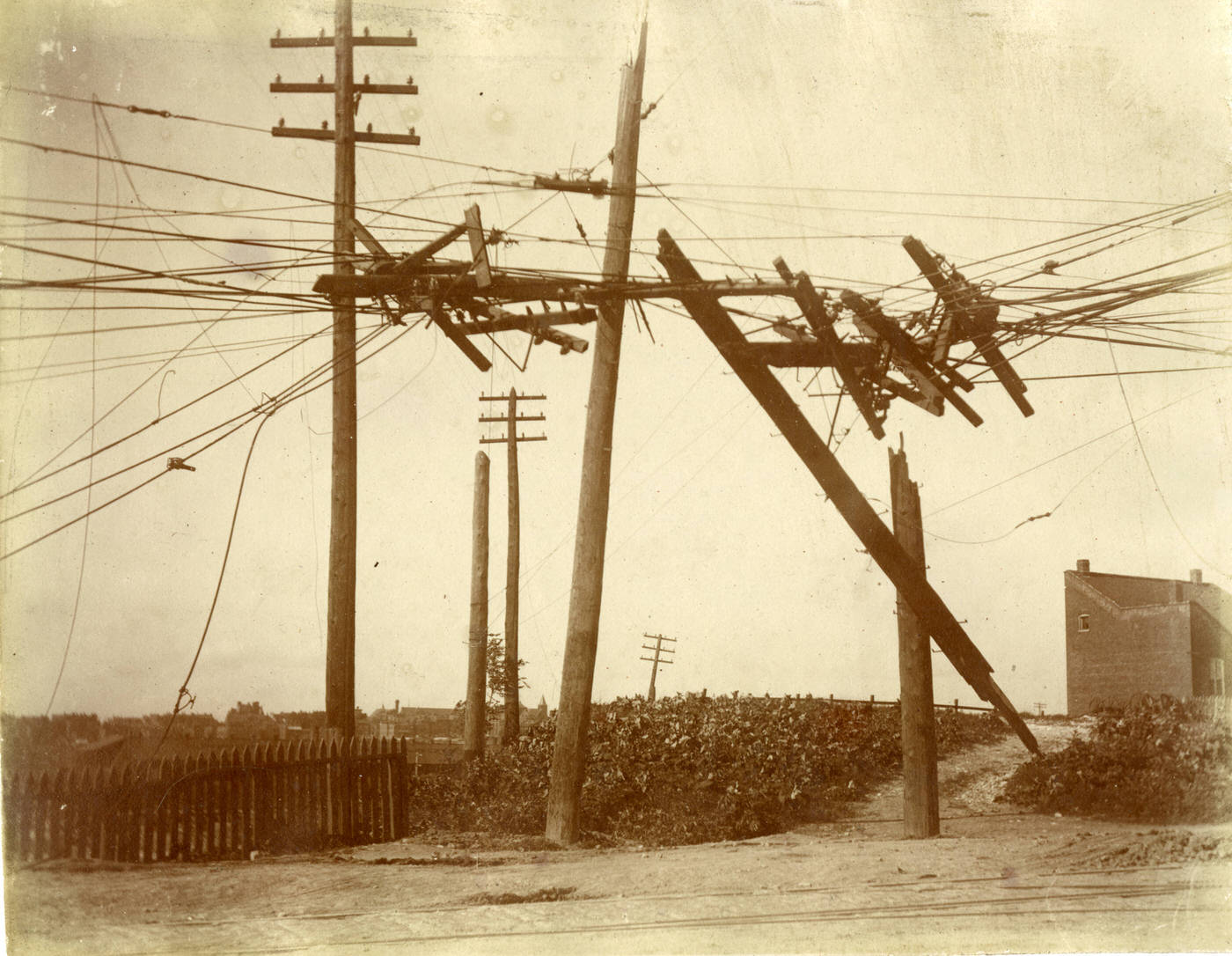

Across the river, East St. Louis faced even more concentrated fury. The tornado, though perhaps smaller in size here, was described as more intense, nearly reaching F5 intensity. It leveled about half of the city. Homes and buildings along the riverfront were completely swept away. The Vandalia railroad freight yards were devastated, with 35 fatalities occurring there. The Big Four and Louisville & Nashville freight sheds were razed. The Relay Depot was obliterated, and the National Stockyards and the Nelson Morris Packing Company plant suffered severe damage. The destruction of the Edison Plant plunged the city into darkness, hampering initial rescue efforts. Hundreds of miles of electric wires and thousands of telephone and telegraph poles were torn down, crippling communication.

The widespread destruction of varied structures, from affluent homes to industrial sites and vital infrastructure like hospitals and power plants, underscores the tornado’s indiscriminate power. The damage to the “tornado-proof” Eads Bridge, particularly the penetration of a wooden plank through its iron plate, became a legendary testament to the storm’s extraordinary force, challenging the technological confidence of the era.

Eyewitness to Horror: Accounts from the Ground

Personal recollections from those who lived through the Great Cyclone paint a vivid and terrifying picture of the storm’s arrival and passage. One eyewitness described a “tense silence, which made people’s ears ring, and a sense of oppression” just before the tornado struck, followed by “a dull drumming sound as of innumerable wings being flapped high in the air, and the swirl of black dust about the sky”. This sensory detail captures the eerie calm and the building dread that often precede such violent weather.

Many accounts highlight what were described as “freak stunts” performed by the tornado, events so unusual they bordered on the unbelievable for those who didn’t witness them. One survivor recounted how, at Koerner’s Garden, a large saloon on South Eighteenth Street that was directly in the tornado’s path, a large wooden clock on the wall remained in place, but its metal internal works vanished. The building itself, remarkably, was not severely damaged despite its windows being open. Another astonishing sight was a grand piano found in a small lake in the middle of Lafayette Park, a considerable distance from any houses. The fire engine at #7 Engine House was reportedly lifted and slammed against a brick house across the street, its horses killed in their stalls. These extraordinary occurrences, whether entirely literal or slightly amplified by the trauma of the event, illustrate the almost capricious and immense power people faced. The sheer force seemed almost supernatural to those who experienced it, with some attributing the bizarre destruction to the storm being “heavily charged with electricity”.

Amidst the chaos, there were also stories of fortunate survival and life-saving decisions. In one instance, a group of neighbors huddled in a basement as the storm descended. In the darkness and fear, someone suggested using Holy Water for protection. A bottle was found and passed around, each person ensuring the water touched them. Only after daylight crept through the windows did the unharmed group discover they had actually been sprinkled with ordinary wash blueing. Another remarkable story of survival involved a Park Avenue streetcar filled with passengers. As the storm hit, the car was pushed backward around a curve and into an alleyway, yet it remained on its tracks, and miraculously, no windows were broken. This occurred just moments before the top two floors of the large Brown Tobacco Factory collapsed into that very alley, burying it under thirty feet of debris. The narrator of this account speculated that if the streetcar had been equipped with modern air brakes, it might have held its ground and been crushed.

A significant act of foresight came from Reverend Irl Hicks, an astronomer and weather forecaster. On the day of the tornado, observing his barometer falling rapidly, he recognized the signs of an approaching severe storm. He promptly notified the Public-School Superintendent, advising that children be sent home. The superintendent heeded this warning. This decision undoubtedly saved many young lives, as several school buildings were later demolished by the tornado. This incident stands as an early example of disaster preparedness, however rudimentary, having a direct life-saving impact, contrasting sharply with the general unpreparedness for a storm of this magnitude in an era without sophisticated weather forecasting technology. It highlights how individual observation, and decisive action could mitigate tragedy.

The Human Toll: Lives Lost and Shattered

The Great Cyclone of 1896 exacted a devastating human price, etching itself into history as one of the deadliest tornadoes to ever strike the United States. Official death tolls list at least 255 individuals killed across St. Louis and East St. Louis. However, some accounts from the period and later analyses suggest the number could be higher, with reports of 306 fatalities and speculation that the true count might have exceeded 400. A significant reason for this uncertainty lies with the uncounted victims from the numerous houseboats on the Mississippi River, whose occupants were swept away, their bodies often lost to the current. This tragic reality underscores the limitations of disaster documentation in 1896 and tragically illustrates how the most vulnerable members of society can become invisible casualties.

In the city of St. Louis alone, a minimum of 137 people perished. Across the river, East St. Louis mourned 118 confirmed deaths, a catastrophic loss for the smaller community. A particularly grim scene unfolded at the Vandalia railroad freight yards in East St. Louis, where 35 people lost their lives. The number of injured was also staggering, with conservative estimates starting at over 1,000 and other reports indicating more than 2,500 individuals suffered injuries.

Beyond the immediate casualties, the tornado inflicted widespread homelessness. More than 5,000 people or, by another measure, 600 families, found themselves without shelter in an instant. They faced the daunting task of finding safety and sustenance in the storm’s chaotic aftermath.

The tornado’s path cut across diverse sections of the city, meaning its victims came from all walks of life. Workers at the Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company, who were in the process of constructing a new thirteen-building complex, were caught in the storm; 13 died when structures collapsed, though many others miraculously survived. Residents of a three-story brick tenement at Seventh and Rutgers Street were less fortunate, with 17 people dying when their building was flattened. The storm showed no favoritism between the “stone and brick houses of the affluent” and the “flimsy wooden houses of the poor”, crushing both. However, the capacity for recovery would undoubtedly differ based on social standing and resources. While the tornado devastated both fashionable districts like Lafayette Square and Compton Heights and poorer areas such as Mill Creek Valley, the aftermath would highlight these disparities. The poverty-stricken families living on houseboats along the Mississippi were among the most exposed and least accounted for, many simply “disappeared into the river”.

While not part of the primary St. Louis vortex, it is a somber note that the broader tornado outbreak on May 27th also claimed the lives of three students at the Dye School in Audrain County, Missouri, illustrating the widespread nature of the day’s destructive weather.

Rescue and Relief

In the terrifying moments and agonizing hours following the Great Cyclone’s passage, the citizens of St. Louis and East St. Louis, alongside individuals from surrounding areas, demonstrated remarkable courage and compassion. As the winds subsided, revealing a landscape of ruin, an immediate wave of volunteerism surged through the devastated streets. People rushed to aid the wounded, digging tirelessly through mountains of debris, often working by the dim glow of torchlight as the destruction of the Edison Plant had plunged the city into darkness. These rescue efforts were relentless, continuing through the night and for several days after; survivors were reportedly still being pulled from the rubble two days later.

The scale of the disaster necessitated an organized response. Members of Light Battery “A” and the First Regiment of the Missouri Volunteer Militia were quickly mobilized. Within just an hour of the tornado striking, thirty-two members were on duty with ambulances and hospital corps, navigating the wreckage to rescue victims and provide medical assistance. The Mayor of St. Louis requested that these military units remain on patrol duty through May 30th to help maintain order and support the ongoing relief operations. A critical challenge was the breakdown of communication systems; with telephone and telegraph wires downed and streets impassable, traditional means of contact were useless. In this environment, members of the bicycle corps of Company “G,” First Regiment, proved invaluable, acting as couriers to summon officers and relay vital messages. This adaptation to simpler technology when modern systems failed highlights the resourcefulness of the responders.

Makeshift hospitals were quickly set up to care for the overwhelming number of injured. In East St. Louis, the situation was so dire that every undertaking establishment had to be converted into a temporary morgue to accommodate the deceased, as formal medical facilities were overwhelmed.

The catastrophe also brought forth inspiring acts of community solidarity. St. Louis’s Black community organized significant relief efforts. “The Committee of Twenty-Five,” under the leadership of Reverend John Turner, actively solicited funds to provide essential aid such as food, shelter, and clothing to those affected by the tornado. Similarly, the “Colored Refugee Relief Board,” managed by Charlton Tandy, undertook comparable work to support the victims. Students from the community also played a role, participating in fundraising drives for those impacted by the disaster. As communication lines were gradually restored, news of the devastation reached the rest of the country, prompting an outpouring of aid and support from across the nation for the stricken cities.

However, the aftermath also revealed a less noble side of human nature. The weekend following the tornado saw an enormous influx of people into St. Louis. While many came to offer help or were simply drawn by a desire to comprehend the scale of the event, not all visitors had altruistic intentions. Reports indicate that over 140,000 sightseers passed through Union Station, eager to witness the destruction firsthand, and tours of the ruined areas were quickly organized. More disturbingly, amidst the chaos and suffering, hundreds of thieves exploited the situation, looting valuables from demolished homes and businesses. This stark contrast between selfless heroism and opportunistic criminality underscores the complex human responses that can emerge during times of profound crisis.

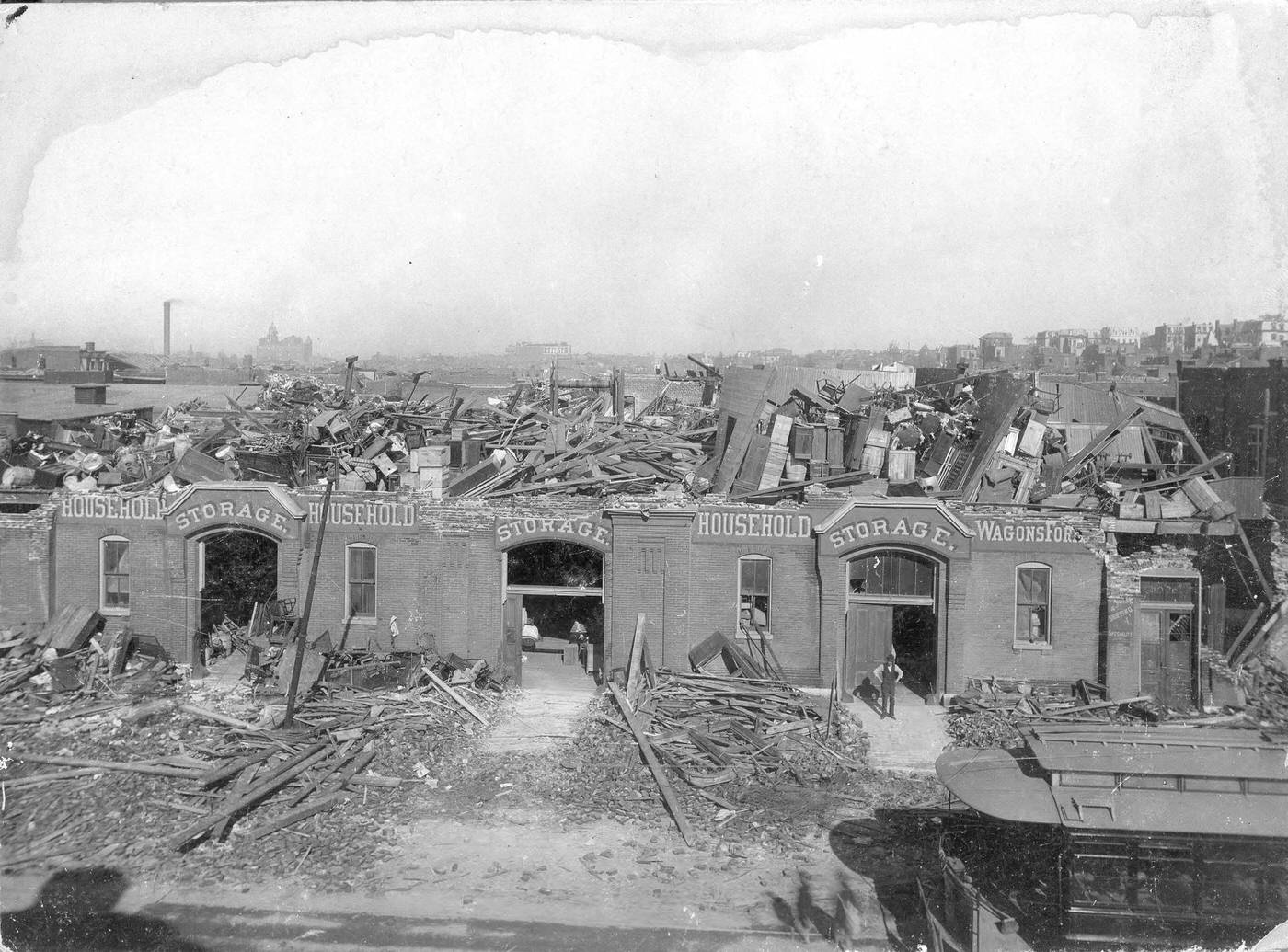

The Great Cyclone of 1896 left behind a staggering level of material loss, the financial impact of which was immense for the era. Initial damage estimates ranged from $10 million to $12 million in 1896 U.S. dollars. The Missouri Weather Bureau Report for May 1896 cited an even higher figure, up to $25 million. When adjusted for inflation and changes in economic scale over time, these figures translate to a modern equivalent ranging from approximately $2.2 billion to as high as $5.92 billion , marking it as potentially the costliest tornado in United States history up to that point. The physical destruction was vast. In St. Louis alone, official reports indicated that over 311 buildings were completely demolished, with more than 7,200 others sustaining severe damage. Across both St. Louis and East St. Louis, the total number of seriously damaged structures reached approximately 12,000.

Despite the overwhelming devastation, the citizens of St. Louis and East St. Louis demonstrated remarkable resilience. Within a few weeks of the disaster, the monumental task of clearing debris and beginning the process of rebuilding was underway. In Lafayette Park, for instance, which had been ravaged by the storm, repairs commenced almost immediately. The rustic wooden bridges that had been destroyed were replaced with more durable and ornate iron ones, symbolizing a commitment to rebuilding stronger than before.

Image Credits: St. Louis Public Library, The State Historical Society of Missouri

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know